Reasons for Robin, #1 and #2

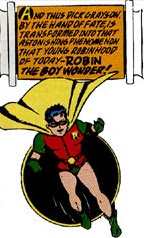

As threatened, here is the first installment of my series-within-a-series that I'm calling "Reasons for Robin." It proposes reasons why the creators of Batman might have introduced Robin, the Boy Wonder, after about a year of solo adventures for the Dark Detective. These postings aren't meant to analyze the Robin characters over the decades, particularly in their own adventures. Rather, I've been cogitating on what the early Robin character brought to the Batman stories.

As threatened, here is the first installment of my series-within-a-series that I'm calling "Reasons for Robin." It proposes reasons why the creators of Batman might have introduced Robin, the Boy Wonder, after about a year of solo adventures for the Dark Detective. These postings aren't meant to analyze the Robin characters over the decades, particularly in their own adventures. Rather, I've been cogitating on what the early Robin character brought to the Batman stories.

Reason for Robin #1: So Batman can have someone to talk to. Back in this posting, I quoted original Batman scripter Bill Finger on his first reason for wanting to give Batman a sidekick:

Back in this posting, I quoted original Batman scripter Bill Finger on his first reason for wanting to give Batman a sidekick:

[Sherlock] Holmes had his Watson. The thing that bothered me was that Batman didn't have anyone to talk to, and it got a little tiresome always having him thinking. I found that as I went along Batman needed a Watson to talk to. That's how Robin came to be.Although comics, with their captions and thought balloons, can let readers see into characters' heads, they're more like dramas than like novels. The medium's emphasis on the visual means that the strongest way to show what characters are thinking is through action or interaction with other characters--i.e., speech. And that means having someone to talk to.

But sometimes Batman didn't say all that much, which brings me to...

Reason for Robin #2: So Batman can have someone not to talk to.

Okay, this is a bit counterintuitive, but it starts with the fact that good storytelling depends on the audience not knowing how things will turn out. If Batman, the world's greatest detective and crimefighter, told Robin everything he was thinking, readers would lose interest long before many stories end.

In a mystery story, once readers figure out whodunit, there's not a lot of suspense left. Imagine following all the brilliant thoughts of Hercule Poirot as he deduces exactly who killed the victims and how, and then imagine reading several more chapters of Poirot summoning the police, Poirot gathering the suspects, Poirot walking through each clue to the crime--when we know all that already! Nothing could be more tedious.

In a mystery story, once readers figure out whodunit, there's not a lot of suspense left. Imagine following all the brilliant thoughts of Hercule Poirot as he deduces exactly who killed the victims and how, and then imagine reading several more chapters of Poirot summoning the police, Poirot gathering the suspects, Poirot walking through each clue to the crime--when we know all that already! Nothing could be more tedious.So Agatha Christie, following Arthur Conan Doyle's model, showed us most of Poirot's cases through the eyes of another character--usually Captain Hastings. He's always lagging behind the great Belgian detective, and we readers therefore read about Poirot's deductions at the same time he presents them to the suspects and authorities. Theoretically, Christie could simply skip telling us Poirot's thoughts as he solves the puzzle, but that would soon seem artificial, and therefore interfere with our reading pleasure.

Though Robin didn't supply the narrative voice of early Batman comics, he was still Batman's Watson. His presence lets us see the world's greatest detective solve the mystery of the month, but we don't have to read Batman's deductions until the story's last page.

There was a similar dynamic when Batman laid traps for criminals, or figured out and prepared to counteract their traps. Again, knowing too much of what's going to happen can sap the interest out of a story. That's especially true of adventure tales, which have to be full of thrilling reverses. Just when things look good, they turn bad. Just when things look horrible, the hero wins!

There was a similar dynamic when Batman laid traps for criminals, or figured out and prepared to counteract their traps. Again, knowing too much of what's going to happen can sap the interest out of a story. That's especially true of adventure tales, which have to be full of thrilling reverses. Just when things look good, they turn bad. Just when things look horrible, the hero wins!By having Robin at Batman's side, but not privy to all the caped crusader's thinking, the comics writers could highlight how good or bad things looked at the moment. Yet their hero could be one step ahead of the plot the whole time. Batman could spring a trap he had prepared long before, or escape from one through a weakness he'd silently spotted. Once again, all the explanations would come in the very last panels.

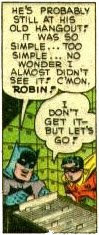

Batman's penchant for secrecy has increased markedly in the modern post-Crisis stories. Sometimes it takes benign forms, as in the Young Justice panels at left, when Tim Drake as Robin has figured out that Batman was secretly looking after his teenaged hero group for several issues now.

Batman's penchant for secrecy has increased markedly in the modern post-Crisis stories. Sometimes it takes benign forms, as in the Young Justice panels at left, when Tim Drake as Robin has figured out that Batman was secretly looking after his teenaged hero group for several issues now.In most stories, however, DC's writers now present Batman's secretiveness as pathological. Long story arcs, such as Bruce Wayne, Murderer?, are built around his inability to open up and level to his family. The two main Robin figures, Dick Grayson and Tim Drake, are always getting on Bruce Wayne's case about that. But after sixty-eight years, we should all be used to Batman not talking to Robin at crucial times. It really does make for better stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment