Happy Holidays from Highlights

Santa Claus, arguably the most prominent figure in wondrous childhood, has been almost entirely absent from the pages of Highlights over the past 30 years. Santa used to appear multiple times in every December issue in stories and images, as did elves and flying reindeer, since the magazine was founded in 1946. Other Christmas-y pages in December Highlights issues of Chistmases past included short non-fiction pieces on, for example, the history of Christmas trees or Christmas celebrations in other countries, and short fiction about children at Christmas who typically learn valuable lessons about giving and kindness. Recurring characters The Timbertoes and The Bear Family celebrated christmas. Overt Christianity was also prominent in the early years of the magazine all year round and the December issues always included bible stories, sheet music of religious carols, and images of the nativity and angels.But what should we expect from a magazine so un-American that it includes no advertising?

Jesus and Santa both appear less and less frequently in Highlights beginning in the 1950’s. By the 1990’s, Highlights is beginning to look a lot less like Christmas. Santa and Jesus are both almost completely absent, as are the decorations, the bright colors, the piles of gift wrapped presents. They’re replaced by pleas to keep Christmas simple, emphasizing time with family and friends, giving to charities, and making presents by hand. Several pages are given to instructions on making homemade presents and homemade decorations. . . .

The children in Highlights are very often white, as I suspect most of their readers are, and main characters in stories and comics in the magazine are most often male, never queer, and pretty much always comfortably middle class. But at Christmas, their anti-consumerist pragmatism is surprisingly non-conformist.

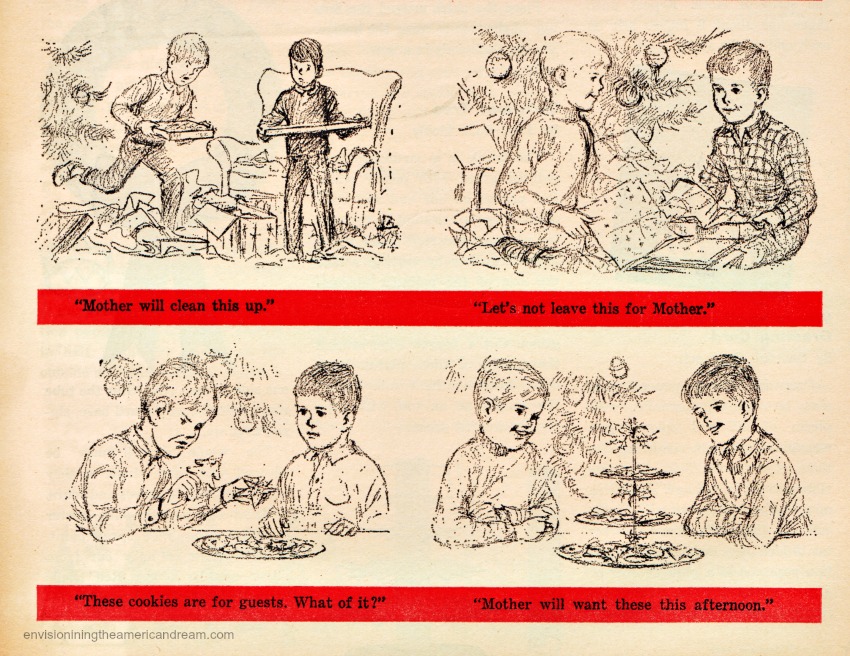

(Above: Goofus and Gallant do Christmas, courtesy of Envisioning the American Dream.)