I read about the child actor Claude Jarman, Jr., before I saw him in a movie, and it wasn’t a complimentary read. The Medved brothers’

Golden Turkey Awards listed Jarman in the category of Most Obnoxious Child Actor.

Though he didn’t have the dubious distinction of winning that award, Jarman’s entry dwelled on his debut performance as Jody in the 1946 MGM adaptation of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s

The Yearling.

Only later did I actually see that movie and assess Jarman’s performance for myself. He performed alongside Gregory Peck, Jane Wyman, and a herd of young deer selected to play one pet. Clearly someone who doesn’t like sentimental stories about wide-eyed children and animals wouldn’t like that film or Jarman’s performance. I think Peck as a young father carried the picture, but Jarman performed his major role just fine.

Of course, it helped that Jarman looked like the illustrations of Jody that Edward Shenton drew for the first edition of

The Yearling. (Scribner’s commissioned more art from

N. C. Wyeth for a deluxe edition the next year.) I came away thinking that Jarman’s performance might be a case of careful casting, director Clarence Brown finding a boy who looked and talked just as that one role required. But, if the Golden Turkey nomination was a fair indication, Jarman wasn’t up to any other part.

Later I ran across Brown’s adaptation of William Faulkner’s

Intruder in the Dust (1947), which I’ve

written about as one of the precursors to

To Kill a Mockingbird. I hadn’t expected to see Jarman again—

The Golden Turkey Awards didn’t mention that film at all. It’s a good movie, and Jarman did a fine job as a southern teenager realizing the racial injustice in his society.

Last week I watched John Ford’s

Rio Grande (1950),

discussed here. Again, there was Claude Jarman, this time playing the estranged son of cavalry officer John Wayne. Again, the Medveds didn’t mention this movie. And again, Jarman did fine with his part. It’s not a deeply nuanced role in a film whose biggest strength is the visuals, but he did all that was asked of him, including a crazy stunt.

How, I wondered, did this supposedly terrible young actor keep doing fine in good movies? In fact, Jarman made only about a dozen films in his whole Hollywood career, so for three to stand the test of time is an achievement. (Two more westerns,

Roughshod [1949] and

Hangman’s Knot [1952], also have fans, but I haven’t seen them.)

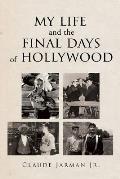

To understand Jarman’s work I sought out his autobiography,

My Life and the Final Days of Hollywood, published in 2018. It’s a short book, straightforwardly told. Just as the title suggests, it combines Jarman’s own life with the change he saw happening around him during his stint in the movie capital in the late 1940s.

As MGM’s publicity machine trumpeted, Clarence Brown spotted Jarman at his school in Nashville taking down a Valentine’s Day display in 1945. Some versions of the story say Jarman had missed a haircut and was thus sporting a rustic look, suitable for Jody. A photo in

My Life and the Final Days of Hollywood casts doubt on that; sent back to a producer in California, that image shows Jarman with hair much shorter than he wore in the movie.

In any event, Brown convinced MGM to bring Jarman and his father out to the coast for a screen test, then to cast the boy as Jody.

The Yearling took almost a year and a half to make in Florida and California, released for Christmas season in 1946.

Jarman arrived in Hollywood (technically Culver City) when the studio system was still intact. MGM provided him with a weekly salary, drama lessons, publicity, and acting assignments whether he was interested in those movies or not. He went to school at the studio alongside other child actors like Elizabeth Taylor, Margaret O’Brien, and Dean Stockwell. It didn’t take him long to realize that he didn’t share their interest in acting or being a star.

A lot of successful child performers are naturally short or bloom late, so they can play younger roles. Jarman, in contrast, grew several inches in his early teens, meaning his height and body no longer fit his baby face. As Harry Carey, Jr., recalled, at fifteen Jarman “was 6'2" and weighed about 160 pounds.” That made it tough for MGM to cast him. In fact, in

Rio Grande Jarman played a West Point dropout—a significantly

older role, albeit one that needed an actor with a young face.

Meanwhile, the studio system was crumbling around him. Between television and the antitrust lawsuit that separated movie studios from cinema chains, the industry changed from assembly line to contingency projects. In 1949, Jarman happily went back to Tennessee. He was a star athlete at his prep school, then enrolled at Vanderbilt. Jarman spent summers or skipped classes to make a few more films, such as

Rio Grande, and entered the business world.

Eventually, however, Jarman found himself back in a wing of show biz, running the San Francisco International Film Festival. He started in 1965, before revival cinema was everywhere, and he tapped his Hollywood contacts to bring special guests up from LA. That experience gave Jarman another couple of chapters of anecdotes and a perspective on the movie business that enriches his whole book.

Notably, Jarman refers to

The Golden Turkey Awards at one point in his memoir, mentioning how his costar in

Fair Wind to Java, Vera Ralston, was nominated for Worst Actress of All Time. Though he makes a point of saying he never read his own reviews, I can’t help but think he knew about the Medveds’ critique of his own acting career. Which I’ve now come to think of as unfair.

Jarman published his memoir through Covenant Books, a self-publisher that markets itself to Christian authors. That probably limits the reach of the book into physical stores and libraries, but there’s a digital edition available. The book is written and produced at a professional level. (Jarman credits

Sloan de Forest with helping him write his story.)

People interested in the history of America’s movie studios should enjoy

My Life and the Final Days of Hollywood, not because it reveals a great deal new but because it shows those details through one wide-eyed child’s perspective. Jarman’s Hollywood career was short and in many ways atypical. But he did fine, and he came out fine.