I mentioned Our Gang cast member Johnny Downs in

this posting on Elmer “Scooter” Lowry going into vaudeville.

Johnny Downs was born in 1913, son of a naval officer, and spent his first years in San Diego. After he showed interest in performing, his mother gave him a Jackie Coogan haircut and brought him to Hollywood.

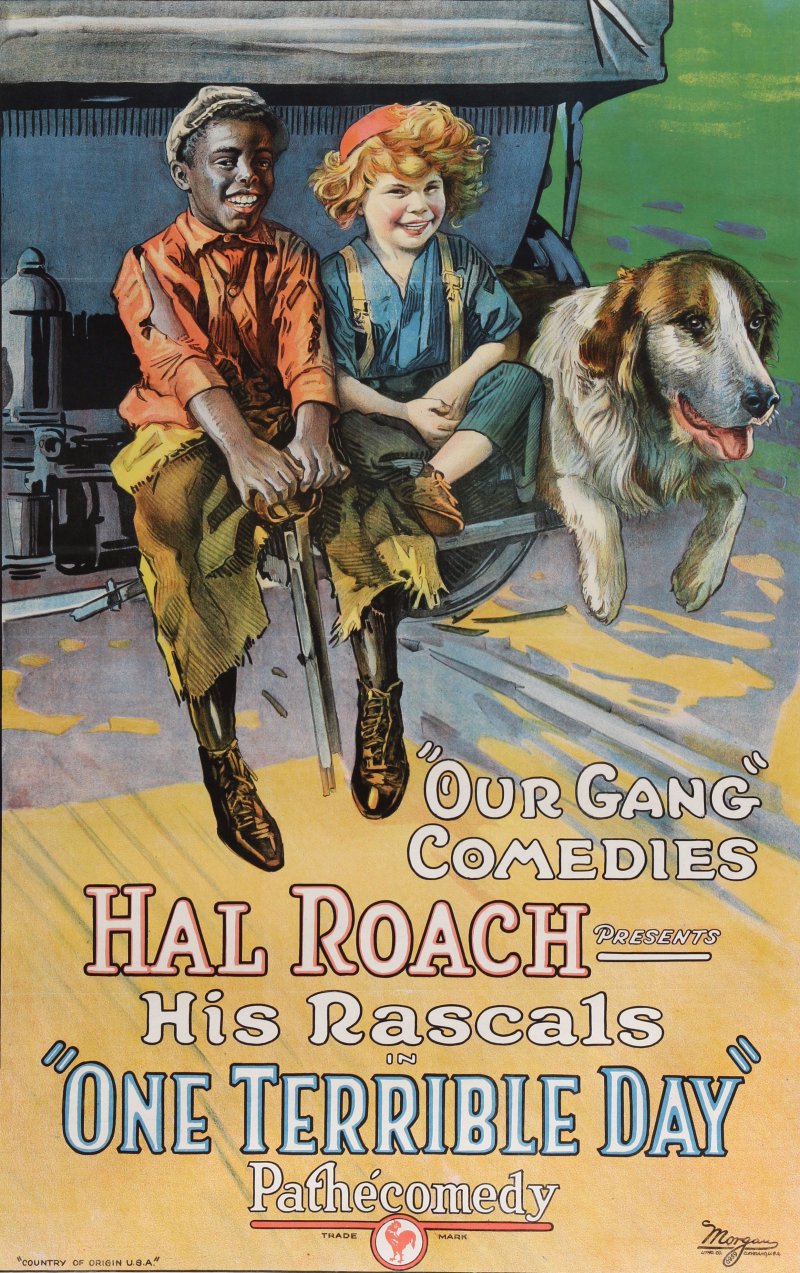

In 1924 Johnny acted in a couple of the kid-gang series launched after Our Gang’s success: the Reg’lar Kids movie “An Afternoon Tee” and the Juvenile Comedy “Wildcat Willie.” Late in that year the Hal Roach Studio hired him as a day player.

At first Johnny appeared in Our Gang films as a antagonist, but with a long-term contract at $50/week (and a new haircut) he became one of the gang.

When the studio announced Johnny Downs had joined the regular cast, it said he was nine years old. (He was eleven.) He made more than twenty Our Gang movies, remaining a regular until he was thirteen.

Johnny Downs was a handsome kid with a winning smile. He was rarely at the heart of the story, but sometimes his part stood out, as when he played a rich kid wanting friends in “Buried Treasure.” In “Telling Whoppers” he was cast as the neighborhood bully tormenting all the other boys; though he threw himself into the role, Johnny was just too naturally sunny to make it work.

In late 1926 the Hal Roach contract ended. Johnny spent twelve weeks in vaudeville before returning to Hollywood. Over the next few months he portrayed the young version of the hero in a few features: the young Tom Mix in

Outlaws Of Red River, the young Fred Thomson in

Jesse James, the young James Murray in King Vidor’s

The Crowd. He made a brief return to the Our Gang unit to play an adolescent magician sporting a fake beard in “Chicken Feed.”

In 1928 Johnny went out on a vaudeville tour with fellow Hal Roach alumni Mary Kornman and “Scooter” Lowry, as

discussed here. He sang a little, danced a little, told stories, showed audiences that sunny smile. Newspapers described his persona as “The All-American Boy.” That tour lasted through August 1929.

During the early 1930s Johnny Downs worked in musical revues, including shows on Broadway. Late in 1934, now an adult, he came back to Hal Roach again for the role of Little Boy Blue in the Laurel and Hardy musical

Babes in Toyland.

In 1935 Downs signed with Paramount. Over the next few years he worked steadily as a juvenile lead, headlining small pictures (

The First Baby,

Blonde Trouble,

Bad Boy) and playing small parts in vehicles for bigger stars (

Algiers,

Pigskin Parade,

The Kid from Brooklyn). The lead role in the drag musical comedy

All-American Co-Ed brought him back to the Hal Roach Studio again. He starred in a series of shorts for Columbia and a serial for Universal.

Of course, it’s harder to be a juvenile lead when you’ve hit thirty. After World War 2, Downs went back to Broadway. Then he tried television, hosting some shows and acting in others. In 1953, turning forty, Downs settled in Coronado, the region where he’d grown up. For well over a decade he was announcer and afternoon host for a San Diego television station, and also worked in real estate.

Johnny Downs never became a big star, but he was undoubtedly a small one, and he worked in show business for almost fifty years. Of all the regular members of Hal Roach’s Rascals in the silent era, Downs enjoyed the biggest and longest adult acting career.