“Every statement is an overstatement”

This passage appeared in a an essay by Adam Gopnik that appeared in The New Yorker in 2008. I’ve found it to offer one of the most useful observations of the millennium.

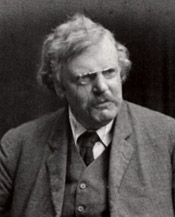

Gopnik was discussing how G. K. Chesterton had gone out of style:

For someone who learned to write before this shift, I say with characteristic understatement and deflection, it’s a bit disconcerting.

Gopnik was discussing how G. K. Chesterton had gone out of style:

The second big shift occurred just after the First World War, when, under American and Irish pressure, and thanks to the French (Flaubert doing his work through early Joyce and Hemingway), a new form of aerodynamic prose came into being. The new style could be as limpid as Waugh or as blunt as Orwell or as funny as White and Benchley, but it dethroned the old orotundity as surely as Addison had killed off the old asymmetry.In the years since 2008, I perceive, our popular rhetoric has undergone the opposite shift. People now once again speak in hyperbole, especially online. We no longer simply have a fun time; we enjoy “the best Day EVER!” We no longer dislike someone; we say they “deserve to die.” I see people express anxiety about not having enough exclamation points in their business emails.

Chestertonian mannerisms—beginning sentences with “I wish to conclude” or “I should say, therefore” or “Moreover,” using the first person plural un-self-consciously (“What we have to ask ourselves . . .”), making sure that every sentence was crafted like a sword and loaded like a cannon—appeared to have come from some other universe. Writers like Shaw and Chesterton depended on a kind of comic and complicit hyperbole: every statement is an overstatement, and understood as such by readers. The new style prized understatement, to be filled in by the reader.

What had seemed charming and obviously theatrical twenty years before now could sound like puff and noise. Human nature didn’t change in 1910, but English writing did. (For Virginia Woolf, they were the same thing.) The few writers of the nineties who were still writing a couple of decades later were as dazed as the last dinosaurs, post-comet. They didn’t know what had hit them, and went on roaring anyway.

For someone who learned to write before this shift, I say with characteristic understatement and deflection, it’s a bit disconcerting.

No comments:

Post a Comment