Grayson’s Future End

Modern comic-book writers often dread big crossover events, at least when they’re not in charge. Whatever storylines they might have mapped out over several issues have to be put on hold for one or two episodes tied into a larger conflict determined by the publisher’s top staff or star writers. But crossovers tend to sell more copies of all the titles involved, and often continue to sell in paperback form, so the industry keeps ordering them up.

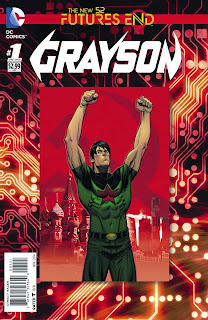

Currently the big crossover event from DC is “Futures End,” not to be confused with the last crossover, “Forever Evil.” (The company seems to have a thing for those initials. I will refrain from making a scatological joke about what they really mean.) “Futures End” is set five years into one possible dismal future for the DC Universe.

As I explored back here, in the DC pantheon Dick Grayson has long represented hope for a better future, so to showcase how awful a future is the company often shows how badly Dick Grayson’s life has turned out. Grayson: Futures End, published last week, is squarely in that tradition.

That situation freed up Grayson writers Tom King and Tim Seeley (they plotted the issue together, King wrote the dialogue). Working within a timeline that’s supposed to be averted, they don’t have to leave the door open to further stories or other crossovers. They can start at Dick’s sad end and work backward—which they do.

Each page in the magazine takes place “Earlier” than the preceding page, hopping backwards in time from five years in the future (as in “Futures End”) to Dick’s childhood. Characters allude to events, promises, and in-jokes that we don’t see for another few page flips. As one commenter noted, the issue is like a sestina, with certain details—ropes, codes, last days—popping up rhythmically. It demands, and rewards, immediate rereading.

I hesitate to call this a self-contained story because it depends completely on readers’ knowledge of the legend established in Detective Comics, #38: when extortionists put acid on the ropes of the Flying Graysons’ trapeze apparatus, causing Dick’s parents to fall to their deaths. But it surely brings its own story to an end (as in “Futures End”).

As promised, King takes the opportunity to offer his “New 52 Universe” explanation for why Robin dresses in stoplight colors. That’s not because Dick as a circus performer and/or little kid likes bright colors, the explanations in some previous versions of the mythos. (The “New 52” Flying Graysons wear blue, and the “New 52” Dick becomes Robin in his mid-teens.) Rather, the colors are Bruce Wayne’s way of making night patrols harder for Dick so he has to be more careful. I’m not sure that will go over well with fans of either character.

Grayson: Futures End also shows Barbara Gordon as Batgirl suggesting that Dick’s ideal romantic partner is someone who treats him like Bruce. Fifteen years ago the company was adamantly against Barbara likening Bruce and Dick’s relationship to a romance. Now DC is embracing the metaphor. But perhaps only in this not-necessarily-so future.

Which brings me to the remaining mystery of this magazine—when its timeline is supposed to deviate from the “New 52” present that DC’s line will presumably return to at the end of the crossover. Does that deviation produce the events we see: Dick and his agency handler Helena Bertinelli becoming lovers, Dick becoming willing to kill? In other words, when exactly does Dick’s life start to turn out badly?

Currently the big crossover event from DC is “Futures End,” not to be confused with the last crossover, “Forever Evil.” (The company seems to have a thing for those initials. I will refrain from making a scatological joke about what they really mean.) “Futures End” is set five years into one possible dismal future for the DC Universe.

As I explored back here, in the DC pantheon Dick Grayson has long represented hope for a better future, so to showcase how awful a future is the company often shows how badly Dick Grayson’s life has turned out. Grayson: Futures End, published last week, is squarely in that tradition.

That situation freed up Grayson writers Tom King and Tim Seeley (they plotted the issue together, King wrote the dialogue). Working within a timeline that’s supposed to be averted, they don’t have to leave the door open to further stories or other crossovers. They can start at Dick’s sad end and work backward—which they do.

Each page in the magazine takes place “Earlier” than the preceding page, hopping backwards in time from five years in the future (as in “Futures End”) to Dick’s childhood. Characters allude to events, promises, and in-jokes that we don’t see for another few page flips. As one commenter noted, the issue is like a sestina, with certain details—ropes, codes, last days—popping up rhythmically. It demands, and rewards, immediate rereading.

I hesitate to call this a self-contained story because it depends completely on readers’ knowledge of the legend established in Detective Comics, #38: when extortionists put acid on the ropes of the Flying Graysons’ trapeze apparatus, causing Dick’s parents to fall to their deaths. But it surely brings its own story to an end (as in “Futures End”).

As promised, King takes the opportunity to offer his “New 52 Universe” explanation for why Robin dresses in stoplight colors. That’s not because Dick as a circus performer and/or little kid likes bright colors, the explanations in some previous versions of the mythos. (The “New 52” Flying Graysons wear blue, and the “New 52” Dick becomes Robin in his mid-teens.) Rather, the colors are Bruce Wayne’s way of making night patrols harder for Dick so he has to be more careful. I’m not sure that will go over well with fans of either character.

Grayson: Futures End also shows Barbara Gordon as Batgirl suggesting that Dick’s ideal romantic partner is someone who treats him like Bruce. Fifteen years ago the company was adamantly against Barbara likening Bruce and Dick’s relationship to a romance. Now DC is embracing the metaphor. But perhaps only in this not-necessarily-so future.

Which brings me to the remaining mystery of this magazine—when its timeline is supposed to deviate from the “New 52” present that DC’s line will presumably return to at the end of the crossover. Does that deviation produce the events we see: Dick and his agency handler Helena Bertinelli becoming lovers, Dick becoming willing to kill? In other words, when exactly does Dick’s life start to turn out badly?

No comments:

Post a Comment