The Last Times We Saw Dick Grayson as Batman

As the weekly Robin has traced, in the Batman comic books Dick Grayson has now taken over the mantle of the Caped Crusader while his mentor, Bruce Wayne, is temporarily dead. Last week I discussed my theory that one of scripter Grant Morrison's inspirations for this plot was a friendly rivalry with Frank Miller, who's been exploring the dynamic of the Dynamic Duo in the All-Star Batman and Robin series.

At Newsarama, a commenter named roshow suggested another source: a series of six "imaginary" stories from the early 1960s showing Dick Grayson as a future Batman and Bruce Wayne's son as a future Robin.

The first of those tales appeared in Batman: From the ’30s to the ’70s, which Morrison read as a child (as did I). He's acknowledged drawing inspiration from "Golden Age" Batman stories.

The first of those tales appeared in Batman: From the ’30s to the ’70s, which Morrison read as a child (as did I). He's acknowledged drawing inspiration from "Golden Age" Batman stories.

However, Robin II was quite a different personality from the boy taking over as Robin now. Bruce Wayne, Jr., was the imaginary future son of the billionaire and Kathy Kane, that era's Batwoman.

The new Robin is Damian, who may be Bruce Wayne's child with antagonist Talia al-Ghul. He's already a well trained fighter, and the new series will be about Dick trying to rein in the boy's killer impulses and teach him to be a better person.

The new Robin is Damian, who may be Bruce Wayne's child with antagonist Talia al-Ghul. He's already a well trained fighter, and the new series will be about Dick trying to rein in the boy's killer impulses and teach him to be a better person.

In contrast, the earlier stories were about a decent kid learning to fight crooks better. As Dick was doing in the "real" stories of the time, Bruce, Jr., fell down a lot. He wasn't sure he could live up to the expectations of either his father or "Uncle Dick."

The Silver Age blog points out that many of those "Batman II" tales ended with Bruce Wayne, Sr., dressing up in his old costume and saving the day. Which didn't make Dick look any more competent than Junior. After all, the name of the magazine was still Batman, not Batman II!

The saga of Batman II and Robin II was the fictional creation of Alfred the butler. Those stories disappeared from the magazines after Batman's "New Look" removed Batwoman and even Alfred (for a time). But perhaps they stuck in Morrison's memory.

Within the current continuity, Dick Grayson took over as Batman for three months of comics in 1994-95. A villain had broken Bruce Wayne's back. His first choice of a replacement had proved even crazier than he is, tossing Tim Drake out of the cave (which opened the door for the separate Robin series).

Within the current continuity, Dick Grayson took over as Batman for three months of comics in 1994-95. A villain had broken Bruce Wayne's back. His first choice of a replacement had proved even crazier than he is, tossing Tim Drake out of the cave (which opened the door for the separate Robin series).

Eventually Bruce defeated his first successor in the most difficult intervention ever, then decided that he needed to retrain. Meanwhile, Dick had left the Titans because of declining sales, so he was available to take over the Batman role. He gave up his Nightwing identity and hid his ponytail under the cowl.

Those stories were collected in Batman: Prodigal, now out of print. (I bought my copy from an English church thrift shop.) Because Tim Drake remained Robin, that book reflects a very different team dynamic from what Miller and Morrison are exploring.

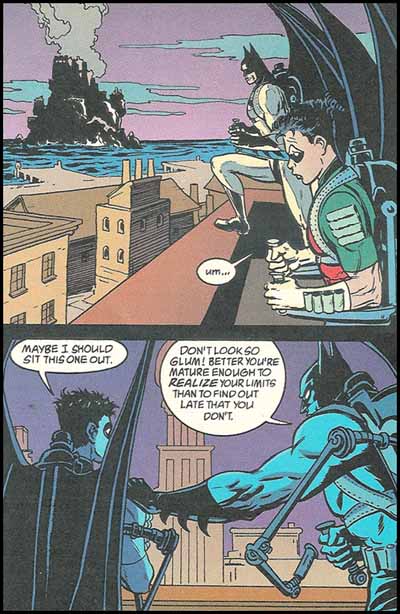

I see that dynamic in this moment, one of my favorites in Batman literature (truncated from Shadow of the Bat, #33, script by Alan Grant and art by Bret Blevins). Dick and Tim are up on a skyscraper, preparing to hang-glide across the harbor.  Tim does an exceedingly rare thing for a superhero, deciding that he's not up for some feat. And Dick supports him. As this exchange shows, they get along. They like and respect each other. They can communicate, decide what's best, and not carry around resentments. Thus, there's little chance of them generating the ongoing conflict that fuels long storylines.

Tim does an exceedingly rare thing for a superhero, deciding that he's not up for some feat. And Dick supports him. As this exchange shows, they get along. They like and respect each other. They can communicate, decide what's best, and not carry around resentments. Thus, there's little chance of them generating the ongoing conflict that fuels long storylines.

Since Prodigal, Dick has dressed as Batman again at least once, for a moment at the start of Batman, #588. Wearing the Batman costume (and elevator boots), Dick walks into a bar and roughs up a hood named "Matches" Malone. The other thugs therefore accept "Matches" as one of them--but he's really Bruce in disguise. Right after this encounter, Bruce gives Dick notes about how he should have played Batman better. Plenty of tension and resentment there.

Both All-Star titles sold big, but All-Star Superman got universally good reviews while All-Star Batman and Robin has been lambasted. Some people love it, to be sure, but part of what they enjoy is how much it ticks so many other people off. DC assured readers that these stories weren't in "regular continuity"--i.e., readers could treat them as imaginary. (As opposed to other

Both All-Star titles sold big, but All-Star Superman got universally good reviews while All-Star Batman and Robin has been lambasted. Some people love it, to be sure, but part of what they enjoy is how much it ticks so many other people off. DC assured readers that these stories weren't in "regular continuity"--i.e., readers could treat them as imaginary. (As opposed to other