What Teen Titans, #0, Tells Us About the New Tim Drake

In Teen Titans, #0, the first thing that boy tells Batman is: “Honestly? It [discovering your secret identity] wasn’t as hard as it would seem.” That’s the same sort of bragging that the character had done in Batman, #0: “You’re not going to throw out the best student in the school”; “I thought it’d be more fun to catch you in the act…a challenge, you know? But you made it ridiculously easy.”

Batman’s response to that boy is, “Hubris is an unattractive quality, Tim.” And indeed the story of Tim in those two magazines is a story of hubris: a teenager so convinced of his intellectual capabilities that he sets out to deduce Batman’s identity and apply for the job of Robin. Furthermore, when Batman doesn’t accept his application, Tim forces the Caped Crusader’s hand, taking a potentially fatal risk that costs him his loving family. The story of Teen Titans, #0, is thus about Tim learning a valuable lesson about life.

Last week I wrote:

Perhaps this is a new characterization of Tim as intellectually snobbish. Stories about him overcoming that flaw could be interesting, though I think they’d undermine some of his appeal for readers. (Shall we see what Teen Titans, #0, brings?)And now we know. James Tynion IV carried out his Batman, #0, assignment to write dialogue not for the Tim Drake most comics fans are familiar with but for another character named Timothy. I still question how his scene makes the SAT the final revelation instead of the police, and the vagueness of the line, “The way you treat your students and your faculty…you’re a bad man, Mr. Renfield.” But in terms of the boy’s characterization, Tynion was right on target.

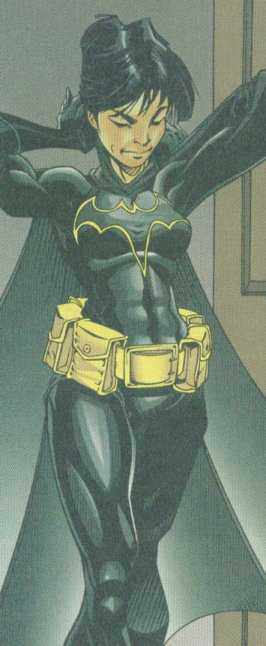

Teen Titans, #0, also tells us that the Tim in those episodes didn’t have the surname Drake until he became Batman’s partner as Red Robin (wearing the 2006-2009 costume). That name change was a last-minute decision by DC Comics editors, Lobdell told CBR. So literally the boy in those scenes was not Tim Drake yet.

I’ve habitually referred to the first and second Jason Todds because I see a major distinction between the pre-Crisis character of that name and the post-Crisis character that everyone now remembers. DC Comics’s recent reboot has preserved the basics of the second Jason Todd even as it added a new layer of details. The iconic origin of Dick Grayson remains fundamentally the same, as always. But the comics now have the first and second Tim Drakes. (The TV cartoon already combined Tim’s name with the second Jason’s history, but that’s another story.)

The first Tim Drake was dedicated and convinced that Batman needed a Robin, but never hubristic like the second. The first Tim had a special link to Dick Grayson; the second has no direct connection. The first Tim figured out Batman’s secret identity; the second only thought he had. The first had a deep unconscious desire for a father figure due to absent and inadequate parents; the second had very supportive parents, whom he endangered and then had to give up to save their lives. Obviously the symbolic value and thus the appeal of the two characters will be different.

There’s plenty of story potential in the second Tim Drake: his feelings of love and guilt for his parents, now in witness protection (and having more children?); his intellectual rivalry with Batman; his need to guard against hubris. Even the enmity of disgraced headmaster Renfield might become the seed for a future plot. But this is not the character fans have followed since 1989.

Another notable pattern from this month’s rebooted Robins is how they’ve been assigned details that once distinguished Batman’s female allies. Nightwing, #0, gives Dick Grayson a highly developed ability to read body language, formerly the hallmark of Cassandra Cain. Teen Titans, #0, shows Tim hacking money from criminals, as Barbara Gordon did when she was Oracle. The same magazine shows Tim tweaking the Gotham underworld to gain Batman’s attention and having that blow up in his face, just as Stephanie Brown did in the War Games crossover. That seems to leave less room for Cassandra and Stephanie to reappear as they did before, but then the Tim Drake they knew has disappeared as well.