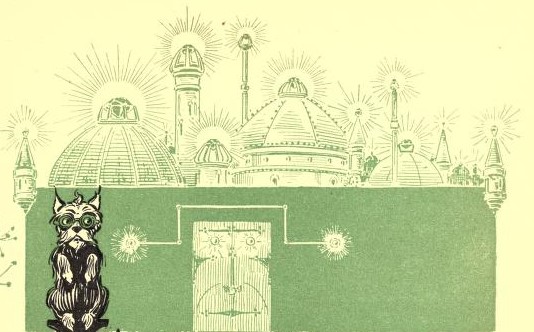

My last posting explored the location of the original gateway into the Emerald City, the one Dorothy and her friends use in L. Frank Baum’s

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

The travelers come to an emerald-studded gate at the end of the Yellow Brick Road. That outer gate leads to a room inside the thick wall with an inner gate on the other side. The little man inside is therefore called the “Guardian of the Gates” even though there is only one opening the in wall. (With his typical inconsistency, Baum also called this character the “Guardian of the Gate,” sometimes within the same chapter.) Thus, the many early references to the city “gates” don’t mean there’s more than one gateway through the wall.

When characters arrive at the city in

The Marvelous Land of Oz, Baum describes their experiences in much the same way as in the first book. The Guardian of the Gates greets them and hands them off to the Soldier with the Green Whiskers. Characters speak of “the gate” of the city.

At the same time, it’s clear that there have been changes in the Emerald City. While before the gate was studded with emeralds, the jewels inside the city only appeared to be emeralds because people wore green spectacles. In

Land the city contains some real jewels. General Jinjur and her soldiers don’t fear blindness without the spectacles.

More pertinent to this inquiry, in

Wizard the Guardian tells Dorothy and her friends there’s no road to the west because no one ever travels that way for fear of the Wicked Witch. In

Land the Sawhorse follows “the road to the West.” It’s not clear whether this path begins at the same gate where the Yellow Brick Road ends.

Finally, toward the end of

Land Baum tells us that “Jinjur had closed and barred every gateway” into the city. While other passages in that book refer to “the gate” as if there’s still only one, the phrase “every gateway” definitely implies that by the time of Jinjur’s brief rule the city had more entrances.

Once again, this fits with what we know about overall politics in Oz. When the Scarecrow becomes ruler of the Emerald City at the end of

Wizard, the Wicked Witches of the East and West have been eliminated. He’s on good terms with Glinda to the south. His friend the Tin Woodman will now govern the west. It would be safe to welcome visitors to his city.

I therefore surmise that between

Wizard and

Land the Scarecrow began the process of building more gates into the Emerald City walls. Perhaps not as large as the original gate, or perhaps (given the peacetime conditions) larger. Likewise, the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman probably promoted the new road from the city to the west.

Commerce and travel between the parts of Oz was probably still slow in this period. The Scarecrow met Gillikins so rarely that by the time of

Land he hadn’t learned they speak his language. Yet General Jinjur could assemble an Army of Revolt of young women from all four outer realms of Oz. (Indeed, Jinjur’s uprising might have been the first pan-Oz movement, at least for several decades.)

Another sign of Oz opening up to travelers appears when we consider the “road to the South” to Glinda’s castle. At the time of

Wizard, that route ran into the Fighting Trees, the walled China Country, a dark and boggy forest, and the Hammerheads, who refused to let anyone hike over their hill. None of those obstacles ever appear in the Oz books again, and characters make many easy land journeys from the Emerald City to Glinda’s home.

What could produce that change? The most likely answer is Glinda the Good Sorceress. With the Wizard in power, she might well have appreciated having several difficult obstacles between his power base and her castle. But once the Emerald City was under a friendly straw-man regime, Glinda probably preferred easier travel.

In

The Emerald City of Oz we learn that Glinda has established several protected little communities in Quadlingland and even manipulates the weather over one of them, Miss Cuttenclip’s village. At the end of that book she unilaterally cuts all of Oz off from our Great Outside World.

Tik-Tok of Oz shows us Glinda’s moving a mountain pass to divert a hostile army outside of Oz—and so casually she doesn’t bother to remember that she’s done so.

Given that record, it’s easy to imagine Glinda magically shifting the road from the Emerald City to her castle to be straighter or safer, or shifting the Fighting Trees, Hammerheads, and other relentlessly hostile obstacles away from it.

The process of connecting the Emerald City to the rest of Oz no doubt accelerated after Princess Ozma took the throne at the end of

Land. Unlike the Scarecrow, she claimed dominion over all of Oz. Her realm is largely peaceful and her rule increasingly secure. It’s no surprise, therefore, that years later

The Patchwork Girl of Oz assures us there are four gateways into the city, one for each quadrant of Oz.