Fawcett’s original Captain Marvel debuted in

Whiz Comics, #2. There was no issue #1.

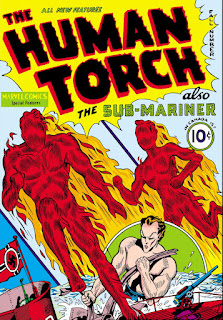

The Human Torch’s kid sidekick, Toro, debuted in

Human Torch, #2. There was no issue #1.

Amazing Man debuted in

Amazing Man Comics, #5, and then headlined

Stars and Stripes, #2. Neither of those comic books had #1 issues, either.

Back around 1940, when those periodicals appeared, publishers tried to avoid #1 issues if they could. To newsstand vendors, the first issue of a magazine looked like an unproven product they could skip.

Fawcett published a couple of “ashcan” issues with different titles to secure its Captain Marvel copyrights and trademarks before sending

Whiz Comics out into the market. Timely dropped a series after one tepid issue and retitled that magazine after its established star, the Human Torch. As for Amazing Man, the Comic Corporation of America simply started its series further along the number line than 1.

When companies canceled one series of stories and started another which seemed to have better prospects, they often changed titles but kept the numbering. Thus, the first

Sub-Mariner Comics evolved into

Official True Crime Cases in 1947,

Amazing Mysteries in 1949, and finally

Best Love, but the numbering climbed steadily from #23 to #33.

After a five-year gap, the Atlas company brought Prince Namor back in 1954, with

Sub-Mariner Comics resuming at issue #33. That was neither exact nor logical, but what mattered was reminding retailers this character was an established draw.

Likewise,

Daring Mystery Comics ran through #8 and was then succeeded by two series, both launching at #9:

Comedy Comics in 1942 and

Daring Comics in 1944. At Charlton in the late 1950s,

Nyoka the Jungle Girl morphed into

Space Adventures after

Space Adventures lost its numbering to

War at Sea.

That preference for presenting a new comics series as firmly established lasted into the succeeding decades. When Marvel shifted its monster and sci-fi magazines to superhero brands, the company changed the magazines’ titles but not their numbering. Thus,

Journey into Mystery, #125, was followed by

Thor, #126;

Strange Tales, #168, by

Doctor Strange, #169; and

Tales of Suspense, #99, by

Captain America, #100. Over at DC,

My Greatest Adventure, #85, led into

Doom Patrol, #86.

To be sure, Marvel’s other regular

Tales of Suspense feature, Iron Man, got its own magazine with a #1 number and a “Big Premiere Issue” decal drawn on the cover. That presaged a new force on the comics scene—collectors who liked to own the first of something special.

In the 1980s the comic-book industry completed a huge shift from newsstands to specialty comics shops. One of the most visible effects was on the #1 issue. Collectors and resellers like that number. Once a liability, a #1 designation is now an asset. Comics publishers seize any opportunity to restart series and put out new #1s. There are, for example, four magazines designated as

Nightwing, #1:

-

the first issue of a 1995 miniseries.

-

the first issue of an ongoing series started in 1996.

-

the first issue of an ongoing series started in 2011.

-

the first issue of an ongoing series started in 2016.

Increasingly new fans complain that all these #1 issues and reboots make it harder to follow the storylines and figure out what back issues to seek. But just as economic incentives made comic books designated #1 rarer in earlier decades, for now those forces push the other way.