With an Uplifted Axe in His Hands

On "Hey, Ocsar Wilde! It's Clobberin' Time!" (yes, that's the blog name), David Petersen shared his interpretation of an important scene from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

On "Hey, Ocsar Wilde! It's Clobberin' Time!" (yes, that's the blog name), David Petersen shared his interpretation of an important scene from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Thanks to Fuse #8 for the link.

Musings about some of my favorite fantasy literature for young readers, comics old and new, the peculiar publishing industry, the future of books, kids today, and the writing process.

On "Hey, Ocsar Wilde! It's Clobberin' Time!" (yes, that's the blog name), David Petersen shared his interpretation of an important scene from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

On "Hey, Ocsar Wilde! It's Clobberin' Time!" (yes, that's the blog name), David Petersen shared his interpretation of an important scene from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Thanks to Fuse #8 for the link.

The gentleman to the right is Gen. and Rep. Benjamin Butler, one of Massachusetts's Civil War heroes. But this is a miniature Butler, made to march along powered by clockwork. In other words, this is the nineteenth-century equivalent of a celebrity Bobblehead doll.

The gentleman to the right is Gen. and Rep. Benjamin Butler, one of Massachusetts's Civil War heroes. But this is a miniature Butler, made to march along powered by clockwork. In other words, this is the nineteenth-century equivalent of a celebrity Bobblehead doll.

This image comes from a new overview of the toys and games in the collection of the Longfellow National Historic Site in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This three-page, illustrated pamphlet is available as a downloadable PDF file.

The three little daughters Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote about in "The Children's Hour" and their two older brothers were probably the owners of these playthings. We can glimpse those children at different ages in the historic site's gallery of ambrotypes and daguerreotypes.

In the pamphlet curator David Daly writes: These toys are excellent examples of what privileged children in mid-to-late 19th century America played with, and how they entertained themselves. The collection also reflects some of the social, technological, and political changes the world at large underwent during the 19th century.

Among the other notable items is a "Kirby's Planchette" from 1860, a predecessor to the oiuja board that was supposed to write out its messages with a pencil instead of spelling them out.

My English teacher during junior year in high school, David Outerbridge, assigned everyone to memorize and recite a poem in class. Cheeky bastard that I was, I chose "An Address to the Rev. George Gilfillan," by William Topaz McGonagall. I still remember most of it, which is probably Mr. Outerbridge's revenge.

And so, for Poetry Friday: All hail to the Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee,

I think that last couplet's daring use of metre is the high point of the poem, but you can find the concluding four lines at McGonagall Online.

He is the greatest preacher I did ever hear or see.

He is a man of genius bright,

And in him his congregation does delight,

Because they find him to be honest and plain,

Affable in temper, and seldom known to complain.

He preaches in a plain straightforward way,

The people flock to hear him night and day,

And hundreds from the doors are often turn'd away,

Because he is the greatest preacher of the present day.

He has written the life of Sir Walter Scott,

And while he lives he will never be forgot,

Nor when he is dead,

Because by his admirers it will be often read;

And fill their minds with wonder and delight,

And wile away the tedious hours on a cold winter's night.

He has also written about the Bards of the Bible,

Which occupied nearly three years in which he was not idle,

Because when he sits down to write he does it with might and main,

And to get an interview with him it would be almost vain,

And in that he is always right,

For the Bible tells us whatever your hands findeth to do,

Do it with all your might.

That site's front page quotes a note from the Rev. Mr. Gilfillan himself, which was probably how he earned this encomium. The minister had this to say about McGonagall's poetry: Dundee, 30th May 1865

I'm in Scotland right now, so this posting is doubly timely.

I certify that William McGonagall has for some time been known to me. I have heard him speak, he has a strong proclivity for the elocutionary department, a strong voice, and great enthusiasm. He has had a great deal of experience too, having addressed audiences and enacted parts here and elsewhere.

George Gilfillan

In May 2007 I wrote about the misuse of the perfectly useful Southern American coinage "you all" in Zizou Corder's Lionboy.

In May 2007 I wrote about the misuse of the perfectly useful Southern American coinage "you all" in Zizou Corder's Lionboy.

I'm now in Falkirk, Scotland, and can report from personal experience that the British nation has its own regional reincarnation of the exclusively-plural "you" (lost after "you" pushed out the singular "thou" to cover both plural and singular numbers).

All that's a long way of saying that tonight at dinner, the waitress repeatedly addressed my father and me as "youse" or "youse guys."

PERMANENT LINK:

4:37 PM

1 comments

![]()

I'm in Great Britain now, so it's an appropriate time to quote Peter Bradshaw in the Guardian on the new Incredible Hulk movie: "Hulk. Smash!" Yes. Hulk. Smash. Yes. Smash. Big Hulk smash. Smash cars. Buildings. Army tanks.

Hulk not just smash. Hulk also go rarrr! Then smash again. Smash important, obviously. Smash Hulk's USP.

What Hulk smash most? Hulk smash all hope of interesting time in cinema. Hulk take all effort of cinema, effort getting babysitter, effort finding parking, and Hulk put great green fist right through it. Hulk crush all hopes of entertainment. Hulk in boring film.  Don't make critics angry. You wouldn't like them when they're angry.

Don't make critics angry. You wouldn't like them when they're angry.

Via Jason Kottke.

Thierry Groensteen's The System of Comics is a literary critic's analysis of how comics work, originally published in French in 1999. My alma mater was the center of deconstructionism in America, so it prepared me for prose like this:

Thierry Groensteen's The System of Comics is a literary critic's analysis of how comics work, originally published in French in 1999. My alma mater was the center of deconstructionism in America, so it prepared me for prose like this:

Let us begin by highlighting this evidence: The page layout does not operate on empty panels, but must take into account their contents. It is an instrument in the service of a global artistic project, frequently subordinated to a narrative, or, at least, discursive aim; if it submits a priori to some formal rule that constrains the contents and, in a certain way, creates them, the page layout is generally elaborated from a semantically determined content, where the breakdowns has already assured discretization in successive enunciations known as panels. However, the page layout cannot be defined as a phase that follows the breakdown, with the mission to adapt it to the spatio-topical apparatus; it is not invented under the dictation of the breakdown, but according to the dialectic process where the two instances are mutually determined.That sort of prose is hard enough to interpret, and this book's translation (by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen) doesn't inspire my trust.

In discussing layout, the text says one of the fundamental qualities to consider is how "discrete" the page is, which seems plausible. (Note how Groensteen calls "discretization" an essential element of panel breakdowns above.) Except that the text opposes this term to "ostentatious," meaning the word should be have been spelled "discreet."

In discussing layout, the text says one of the fundamental qualities to consider is how "discrete" the page is, which seems plausible. (Note how Groensteen calls "discretization" an essential element of panel breakdowns above.) Except that the text opposes this term to "ostentatious," meaning the word should be have been spelled "discreet."

PERMANENT LINK:

8:17 AM

2

comments

![]()

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo. Photo by Alex Rettelschneck from the EPA's Earth Day 2008 photo contest.

Photo by Alex Rettelschneck from the EPA's Earth Day 2008 photo contest.

Last week Publishers Weekly ran an interview with Diana Wynne Jones on the occasion of the landing of House of Many Ways, the second sequel to Howl’s Moving Castle. She had some interesting comments on her working methods. You’ve said you don’t start out with a thoroughly plotted-out book. What do you start out with, when you begin writing?

I’m much more comfortable with an outline myself, but results are results.

I start out with people very often. Also some very, very clear scenes from the middle of the book. And usually a notion of how it’s going to go in the end, but that isn’t always the case. But it’s the clear picture from the middle that’s the important bit, I think. In the case of House of Many Ways, it was the bit when Peter first comes in out of the rain into all the bubbles in the kitchen and Charmaine reaches out and shuts his mouth with a clop. Because that for some reason was a very enduring image and I knew that was in there somewhere. But as I say, the Lubbock, which came just before that, was completely uncharted.

When I used to go and visit schools I always used to shock the teachers because I used to tell the kids that I didn’t plan it out, I waited to see how we got from the beginning to the picture I’d got of the middle of the book, or somewhere into the book, anyway. They were always very shocked. Because they always insisted on all their kids planning it out in advance, and I did sort of plead with them that this was not always necessary. In fact, some people are better for making it up as it goes along.

If I try to plan anything out in that kind of detail it just goes completely blank on me. And I don’t understand what I’ve written as a plan. I just found a plan several weeks ago, actually, when I was looking through stuff to see what I’ve got. And I looked at this plan, and I knew it wasn’t any plan of any book that I’d actually written, and I could not understand a word of what I’d done.

Jones’s choice to name a villainous character after a city in Texas reminds me vaguely of a book that Douglas Adams published a few years ago.

They're action figures. And superhero statuary, whether articulated or still, turn out to be an important revenue stream for the big comics companies these days. They're probably the first limited-edition works of art in the history of the world designed to look good in an office cubicle.

They're action figures. And superhero statuary, whether articulated or still, turn out to be an important revenue stream for the big comics companies these days. They're probably the first limited-edition works of art in the history of the world designed to look good in an office cubicle.

Greenpinoy offers a handy impromptu exhibit of various action figures of Robin, and this is by no means an exhaustive collection. He shows three variations on Nightwing, in each of his major costumes. And there are at least forty different ways you can buy Batman. The DC Direct line offers figures based on different artists' depictions of a character, such as Tim Sale's spindly Robin, Alex Ross's grownup Robin, and Mad magazine's parody Robin.

The DC Direct line offers figures based on different artists' depictions of a character, such as Tim Sale's spindly Robin, Alex Ross's grownup Robin, and Mad magazine's parody Robin.

The next step up in the hobby seems to be posing your dolls action figures in dramatic photographs, such as these posted to Flickr by Shaun Wong, Graphic Knight, and dreamonix.

My brother had a Mattel Batman and Robin set for a while. As I recall, we spent very little time playing with them, but they nevertheless managed to end up with practically none of the removable accessories left.

At A Year of Reading, Mary Lee posted a report on Scott McCloud's public interview of Jeff Smith, creator of Bone, in conjunction with those exhibits of Smith's work in Columbus, Ohio, last month. She wrote: Insider trivia: Check for similarities between Smith's dragon and Doonesbury's Zonker.

Below is an image of a limited-edition, cold-cast statue of that red dragon, sculpted by Randy Bowen for Graphitti Designs.

Eric Velasquez created this image to illustrate Houdini: World's Greatest Mystery Man and Escape King, a picture-book biography by Kathleen Krull. It shows the young Erich Weiss working on his acrobatic act. Where could an artist find a visual reference for that unusual activity? At right is the watermarked comp of a stock photo credited to Jupiter Images, distributed on a CD by ThinkStock. In fact, it's the image on the cover of that CD.

At right is the watermarked comp of a stock photo credited to Jupiter Images, distributed on a CD by ThinkStock. In fact, it's the image on the cover of that CD.

As a writer, I'm always intrigued to get such a peek at how some artists work. I knew illustrators had such resources available for common poses, but what about the uncommon? Stumbling over this resemblance led me to looking up resources on more extreme poses and personas.

For example, there's Buddy Scalera's Visual References for Comic Artists, three CD-ROMs of beefy men and whippety women acting out various physical melodramas. Or The Fantasy Figure Artists Reference File copyright-free book/CD, "allowing illustrators to swipe them directly and paste them into their own computer art projects."

PERMANENT LINK:

9:12 AM

0

comments

![]()

Yesterday I described how three American fantasy novels published over the last fifteen years have, in somewhat different ways, linked Native Americans and magical races. Those books are:

The latter two books include young Americans of indigenous descent among their secondary protagonists. (The first includes a young Latino character as a primary protagonist, and we can discuss how much indigenous ancestry is part of the Latin American heritage.)

Naturally, since those books are fantasies, the Native American characters are caught up in magical experiences along with those of European or other ancestries. However, it strikes me as notable that these books don't just link individuals to secret knowledge, powers, or experience. They link entire groups.

The Quileute in Twilight have made a pact with neighboring vampires, and many of them turn out to be werewolves. The mythical Kurbs in City of Light, City of Dark have, as a whole, sold Manhattan to European settlers. Summerland includes an individual young protagonist of Salish descent, but in this respect I'm thinking of the Indian-like ferrishers, an entire race of magical little people.

Furthermore, while all fantasies have to be governed by rules, these books seem to go further than most in presenting their conflicts as based on age-old agreements or treaties. The Kurbs require a yearly tribute. Summerland involves contracts around baseball games. In Twilight, as I wrote above, there's a "treaty" between the Quileute and the vampires. Evidently, the thought on Native Americans brings up the thought of such age-old contracts.

Incorporating Indian characters or traditions helps to establish a fantasy as American rather than stuck within those dominant British and other European traditions; Chabon has spoken explicitly about that goal in writing Summerland, which also includes the heroes of traditional American folklore (and fakelore), as well as a whole lot more.

In that regard, I think Native American supernatural traditions are as ripe for picking as those from other cultures. However, authors have to be aware that their readers, unfamiliar with the nuances of other cultures, might not be able to distinguish fictional traditions from real ones, or entertaining stories from sacred ones.

Most problematic to me is how these depictions of Native Americans as, in different ways, linked to the supernatural might color readers' impressions of today's Native Americans. Do American Indians really have ancient connections to magic (like Meyer's Quileute)? Are they, despite historical disfranchisement and poverty, secretly powerful and demanding (like Avi's Kurbs)? In such stories, do Native Americans end up seeming as real as the other human characters, or do they come across as a set of fairy-tale creatures (like Chabon's ferrishers)?

City of Light, City of Dark is a hybrid of middle-grade novel and middle-grade comic with words by Avi and art by Brian Floca. Published by Richard Jackson/Orchard in 1993, it was probably a few years ahead of the market. (Compare how the current cover art at left is divided into panels while the first edition's cover offered no hint of the comics form to be found inside.)

City of Light, City of Dark is a hybrid of middle-grade novel and middle-grade comic with words by Avi and art by Brian Floca. Published by Richard Jackson/Orchard in 1993, it was probably a few years ahead of the market. (Compare how the current cover art at left is divided into panels while the first edition's cover offered no hint of the comics form to be found inside.)

Summerland by Michael Chabon, published in 2002, is a doorstop children's fantasy that combines baseball, dirigibles, interdimensional travel, changelings, and a mephistophelean trickster legend into a big stew (which could have been simmered down a bit more).

Twilight by Stephenie Meyer is the novel that started the current boiling-hot series for teens, about vampires and the girls who love them too much. I haven't read it, so I'm going by what Debbie Reese has had to say.

What do these three disparate fantasies for young readers have in common? They all in different ways portray Native American nations as connected to ancient, magical races, knowledge, and/or power.

City of Light, City of Dark's prologue describes creatures named "Kurbs," who owned an Island as well as the sky above it. . . . Years ago, when People first came to the Kurbs' Island, they wanted to build themselves a City there. First, however, they had to ask permission of the Kurbs.

Since the island is obviously Manhattan, that puts the the Kurbs in the place of the Manahatta group of Lenape who made the famous deal with Peter Minuit in 1626. Except that the Kurbs have their own dimension and remain powerful enough to demand a yearly tribute. Summerland alludes or makes use of Native American traditions in at least four different ways. The main villain is the trickster Coyote in Southwestern Native American (and Norse) myths, and other supernatural characters come from Native American legends.

Summerland alludes or makes use of Native American traditions in at least four different ways. The main villain is the trickster Coyote in Southwestern Native American (and Norse) myths, and other supernatural characters come from Native American legends.

Secondary protagonist Jennifer T. Rideout and her family are Salish Indians. Yet Jennifer seems to derive much of her non-baseball-related knowledge from an ersatz Indian source, as Michael Chabon told Salon: There's this bit about this defunct quasi-Boy Scout organization called the Braves of the Wa-He-Ta. There's this official tribe handbook that Jennifer T. is given, and it comes in handy. . . . Even though it was written by a guy named Irving Posner in Pittsburgh in 1926 or whatever.

Obviously, Chabon is here playing with how mainstream American culture has occasionally claimed the value or "authenticity" of indigenous traditions without necessarily reflecting those traditions.

Summerland also introduces a race called ferishers, which is an old European term for fairies. They're small, magical, ancient, and demanding--like those fairies. But the text also links them to the original inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest. They're described on Wikipedia as "small Indian looking people," and at Baseball Almanac as the "small American Indian-like ferishers." Reviewer Stephen E. Abbott says the ferishers live in "an alternate dimension governed by Native American mythology and the rules and regs of baseball," though that understates the elements of other mythologies in this smorgasbord. Finally, Twilight includes characters from the Quileute people of Washington. In this fictional world, many of the Quileute, including secondary protagonist Jacob, are werewolves, and they've made an uneasy truce with nearby vampires.

Finally, Twilight includes characters from the Quileute people of Washington. In this fictional world, many of the Quileute, including secondary protagonist Jacob, are werewolves, and they've made an uneasy truce with nearby vampires.

I suspect folks might be able to offer other examples of recent American fantasy stories linking Native American groups and the magical world.

TOMORROW: Thoughts on the meanings of this pattern.

I'm conferencing once again, so today's weekly Robin is a pointer to the "Shocked Robin" cover generator.

Back in 2004, folks on the Collectors Society bulletin board noted how many issues of Detective Comics and Batman from the 1950s showed Robin in the lower right corner, looking shocked.

Of course, for variety there were also some covers on which he appeared in the lower left corner, looking shocked.

I came to the same conclusions about this pattern as Mark Engblom at Comic Coverage:

So what other works of art, book covers, or family photos could get an extra charge of drama from a shocked Robin in one corner?

So what other works of art, book covers, or family photos could get an extra charge of drama from a shocked Robin in one corner?

PERMANENT LINK:

9:46 AM

2

comments

![]()

In April, Publishers Weekly reported what seemed like an innocuous development in the British publishing industry:

In April, Publishers Weekly reported what seemed like an innocuous development in the British publishing industry: After more than three years of consultation and research, the Publishers Association's Children's Book Group in the U.K. has announced that from fall 2008, all new children's books will carry age guidance.

It took about a month to produce this website/petition from "writers, illustrators, librarians, teachers, publishers and booksellers" protesting the change. Curiously, though we children's-lit folks disdain "celebrity" when it sells books by people who don't know how to write, the industry press on this petition focuses entirely on the big names among the petitioners: Philip Pullman! Michael Rosen!

Research among retailers and consumers, children and adults alike, shows that 86% of book buyers backed the idea, with 40% stating that they'd be more likely to buy the books if they carried guidance on age suitability. As a result, the guidance, based on content and divided into 5+, 7+, 9+, 11+ and 13+, will be included on book jackets and covers.

These "No to Age Banding" folks say they believe it "highly unlikely, despite the claims made by those publishers promoting the scheme, to make the slightest difference to sales." What's the evidence behind their belief? Do they have their own competing survey, or point to methodological flaws in the one reported above? Nope. In fact, offering no evidence at all, the website reflects ideology rather than knowledge.

I had plenty of discussions about how to designate target readers' ages when I was a full-time book editor. As folks might suspect, it was all about marketing. Of course, so is a lot of publishing. In this case, marketing meant making it easier for your target customers to decide to buy your product. The age level was just one clue buyers wanted, alongside the cover copy, cover art, and their knowledge of their own tastes and interests.

I really have to question the wisdom of children's-book creators and promoters protesting what 86% of their customers say they want. That's dismissing the wishes of six out of seven potential readers--with, as I noted before, no evidence.

My eyebrows go up even higher when I see the campaign's phrase "publishers promoting the scheme," as if there were some nefarious purpose behind this change. Publishers, authors, and booksellers are often at odds over money and other issues, but the one thing they should have in common is wanting to sell more books.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:12 AM

2

comments

![]()

Years ago, I subscribed to the Snopes.com weekly update, keeping me abreast of the latest internet urban legends and rumors. I'd noticed a pattern over the past several months, and finally got around to checking out the numbers.

As of last Saturday evening, Snopes listed eighteen rumors about Barack Obama, only one deemed true and eleven false. (The rest are either mixed or undeterminable.)

The site had catalogued twenty-six rumors about Hillary Clinton and her husband, one deemed true and fourteen false.

For John McCain, the site had only three rumors, two of them true and none false.

So a majority of rumors sent around the internet about the leading Democratic candidates have been false. Not just mixed or indeterminate, but demonstrably false. Meanwhile, very little has been posted about the leading Republican, despite his years of political prominence, and the rate of accuracy of items about him is much higher.

I checked other recent national candidates, and the same partisan pattern shows up. Mitt Romney: 1 out of 1 true. John Kerry: 10 out of 22 false, only 3 true. Mike Huckabee: 1 out of 1 true. Even George W. Bush, the highly visible and controversial subject of 47 rumors, has more labeled true (20) than false (16).

So the internet rumor chain that Snopes tracks has spread more rumors about Democrats than Republicans, and more lies about Democrats than true stories about them.

Because there are so few completely true rumors about Democratic candidates, it's easy to check those few and see that they're uncomplimentary, as in the single true Clinton rumor, about a soldier who disliked shaking hands with her. On the other hand, the two true rumors about McCain are both complimentary. One is about his sons' military service. The other is about his present wife, and praises her while leaving out all unfavorable information.

Putting those patterns together raises some disturbing questions. Which party's loyalists seem more likely to spread these sorts of rumors? How much do they respect the truth? And how gullible do they expect the messages' recipients to be?

I'm reminded of the first Republican president's statement that you can fool some of the people all of the time. Perhaps those are the folks the party's present-day strategists consider "our base."

[I wrote this essay well before today's news reports that the Obama campaign has set up a Fight the Smears webpage in response to such rumors, and that "For the third time in less than three weeks, Fox News Channel has had to acknowledge using poor judgment through inappropriate references to Senator Barack Obama."]

This week saw the release of yet another study of children's reading habits, an annual survey commissioned by Scholastic from the research company Yankelovich. As reported by Publishers Weekly, it found that "pleasure reading in children begins to decline at age eight and continues to do so into the teen years."

This week saw the release of yet another study of children's reading habits, an annual survey commissioned by Scholastic from the research company Yankelovich. As reported by Publishers Weekly, it found that "pleasure reading in children begins to decline at age eight and continues to do so into the teen years."

That finding isn't new, and many reactions to it aren't new, either. WSB radio in Atlanta began its report, "Kids just aren't reading like they used to. And indications are the trend is getting worse." Actually, the report found that the trend was staying the same. As Jane Henderson at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch book blog wrote, the survey "tells us pretty much what we already knew."

Despite headlines highlighting decline and serious expressions of concern, it's quite easy to find a lot of reassurance in this report. Most kids are all right, even by fuddy-duddy standards:

although children can readily envision a future in which reading and technology are increasingly intertwined, nearly two thirds prefer to read physical books, rather than on a computer screen or digital device. Additionally, a large majority of children recognize the importance of reading for their future goals, with 90% of respondents agreeing that they “need to be a strong reader to get into a good college.” . . .The results are in line with sociological norms:

Nearly one in four children was found to be a “high frequency” pleasure reader (reading daily), with an additional 53% qualifying as “moderate frequency” readers, reading for pleasure between one and six times per week.Which leaves about a quarter reading infrequently--a bell curve.

Many children in the USA are too busy, too distracted and, in some cases, too tired to read books for fun, a new survey finds, suggesting that schoolwork, homework and diversions such as YouTube and Facebook keep them from regularly enjoying a good book.(Note the value judgment in the phrase "good book.")

Nearly two-thirds of children ages nine to 17 “extended” the reading experience online, including activities such as visiting an author’s Web site, using the Internet to find books by a particular author or visiting a fan site.Where's the real zero-sum game? The second most common reason children gave for not reading more for pleasure was: “I have too much schoolwork and homework.” In other words, they're reading a lot. (They may even enjoy some of that reading.) But it's reading for school, not for pleasure.

parents who read frequently were found to be six times more likely to have children that read often, compared to those who read infrequently. Around one quarter of parents (24%) said they read frequently, up from 21% in the 2006 survey.Which correlates mighty closely with the "Nearly one in four children" who said they read frequently for pleasure. Furthermore, the drop in kids' pleasure reading at age eight corresponds to when "the frequency with which parents read to or with children drops sharply." (Not that we can be sure that one change causes the other.)

PERMANENT LINK:

8:46 AM

1 comments

![]()

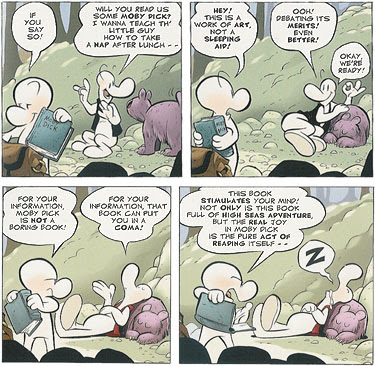

Fone Bone, the central character of Jeff Smith’s Bone comics, and his contented cousin Smiley Bone look for different things in a work of literature. “Debating its merits,” indeed.

“Debating its merits,” indeed.

These panels, as is evident from the color, come from the ongoing reissue of Bone by Scholastic. Specifically, from volume 5, Rock Jaw: Master of Eastern Border. Read them all.

Last week Bowker, the Books in Print people, issued a report on the state of the American book industry, which Publishers Weekly summarized in this article.

Last week Bowker, the Books in Print people, issued a report on the state of the American book industry, which Publishers Weekly summarized in this article.

Bowker now counts new print-on-demand books separately from books printed in a traditional way instead of including everything with an ISBN in the same count. That's because the new p.o.d. technology is causing a huge spike in the availability of books that don't physically exist until someone orders them. In 2007 the number of new traditionally printed titles (or editions) rose only 1%, to about 277,000. However, "the output of on-demand, short run and unclassified titles soared from 21,936 in 2006 to 134,773 last year."

According to PW: The new segment includes traditional books printed by mainstream publishers using print-on-demand technology, public domain titles published through p-o-d as well as titles from self publishers and very small independent press[es] that use p-o-d.

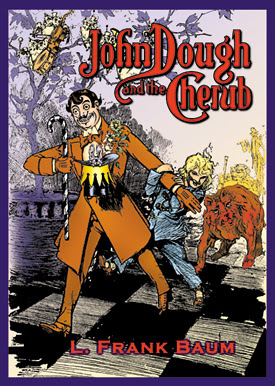

One of those small presses is Hungry Tiger Press, publisher of the new edition of John Dough and the Cherub that I've been pushing discussing in a detached, scholarly manner over the past week or so.

David Maxine started Hungry Tiger Press before print-on-demand books were possible, and has issued many books (and a Grammy-nominated CD) using older manufacturing methods. But p.o.d. makes the economics of niche publishing much more workable. With good design and production values, a volume published through p.o.d. technology looks just as good as a volume published the usual way.

Some people associate p.o.d. publishing with self-publishing. And indeed the new technology makes it easier than ever to print a poorly written, unedited, ineptly laid out, and unproofread manuscript. A lot of those 135,000 new p.o.d. titles issued last year are public-domain books churned out by "presses" that are nothing more than websites.

However, print-on-demand offers many benefits, such as making a book like John Dough and the Cherub available once again to libraries, researchers, and Baum fans. With, I hope I can say, some added value in its new introduction. Last week, Public Affairs turned to p.o.d. to fulfill the big demand for Scott McClellan's confessional. In the next few years, scholarly publishing and other niches will migrate to that form of manufacturing, and it will be fully integrated into the traditional book industry.

When I started researching John Dough and the Cherub, one of my to-do's was to find a copy of The Gingerbread Man, an "Oz-Man Tale" that L. Frank Baum published with Reilly & Britton in 1917. Bill Campbell at The Oz Enthusiast offers a look at the other five in this six-volume series. (Click on his big photo for an even bigger one.)

When I started researching John Dough and the Cherub, one of my to-do's was to find a copy of The Gingerbread Man, an "Oz-Man Tale" that L. Frank Baum published with Reilly & Britton in 1917. Bill Campbell at The Oz Enthusiast offers a look at the other five in this six-volume series. (Click on his big photo for an even bigger one.)

I thought there was a chance that The Gingerbread Man might reveal Baum's initial plans for John Dough, before he received Edward Bok's rejection of the manuscript and advice to include a young co-protagonist. Given what I knew about Baum, it seemed conceivable that he'd grabbed a chance to publish a "Gingerbread Man" manuscript he'd set aside.

Instead, The Gingerbread Man and another volume in the same series, Jack Pumpkinhead, displayed a level of recycling that I hadn't imagined.

To create these 64-page books, the publisher took the plates of the first 50+ pages of John Dough and the Cherub and The Marvelous Land of Oz, added new frontmatter, and had (I presume) Baum draft a quick ending to the stories.

Thus, The Gingerbread Man ends with John Dough finding a new home on the Island of Phreex. Someone traced John R. Neill's drawing of the Fresh Air Fiend who welcomes John to create a slapdash decoration for that final chapter. (The firm didn't try to duplicate Neill's handsome illustrated and hand-lettered chapter titles.) This book has no Chick the Cherub, no Para Bruin, no Mifkets, no hero's journey for John.

In the end, The Gingerbread Man did offer me a clue about what Baum had submitted to Bok. It confirmed how willing he was to milk his existing material. That convinced me that he took off from his initial chapters for Bok in a new direction but didn't rewrite a word of what he already had.

As for the Jack Pumpkinhead volume, it ends with Tip, Jack, and the Sawhorse arriving together at the Emerald City and deciding it will be a nice place to stay. They don't get separated along the yellow brick road, Tip doesn't meet General Jinjur, and Jack doesn't have his comically translated conversation with the Scarecrow. Most significantly, in this version of Oz, there's no Princess Ozma. It's the start of an alternative Oz universe--published under Baum's own name.

I'm attending a history conference this weekend, which makes this weekly Robin mercifully short. All I offer is a link to Ethan Persoff's scans of an ersatz, one-color Batman and Robin comic from Vietnam in the 1960s.

The popularity of the television show and comic books imported by American servicemen apparently spurred some local comics creators to make their own adventure. And in Vietnam, Robin got to be invisible!

In some ways, L. Frank Baum's John Dough and the Cherub is deeply rooted in fairy-tale traditions. It was clearly inspired by the folktales of a gingerbread man or other baked good running away from its makers, and there are stock characters like the dying little girl and the ruthless Arab.

But one aspect of this fantasy was revolutionary: the character of Chick the Cherub has no gender. Chick acts just as boisterous as a stereotypical male and just as loving as a stereotypical female. Living in a somewhat futuristic society, the Cherub is dressed loose pajamas and sandals, and the hairstyles of that decade (as well as ours) meant that long hair was no clue to a child's gender. Furthermore, as I discussed in this posting, being gender-neutral isn't what makes Chick unusual. Rather, that appears to be a natural outcome of being an Incubator Baby--the equivalent then of a test-tube baby today. In essence, Baum was telling Americans that the same modern world that could now save their little premature babies was also rendering their notions of masculinity and femininity obsolete. Baum was the son-in-law of suffrage activist Matilda Joslyn Gage, after all.

Furthermore, as I discussed in this posting, being gender-neutral isn't what makes Chick unusual. Rather, that appears to be a natural outcome of being an Incubator Baby--the equivalent then of a test-tube baby today. In essence, Baum was telling Americans that the same modern world that could now save their little premature babies was also rendering their notions of masculinity and femininity obsolete. Baum was the son-in-law of suffrage activist Matilda Joslyn Gage, after all.

Baum had played with the idea of switching genders in several preceding books. The young hero of The Marvelous Land of Oz becomes the young title character of Ozma of Oz. A fairy in The Enchanted Island of Yew experiences a year as a young prince. In Queen Zixi of Ix and the short story "The Witchcraft of Mary-Marie," magic-workers put on the form of the opposite sex.

But Chick is different. Chick isn't spending some time as a female and some as a male. Chick is happy and healthy with no gender identity at all. I don't know of any other example of children's literature asking readers to identify with such a child until the didactic Free to Be You and Me in 1972.

Baum and his publisher made this mystery the center of John Dough and the Cherub's marketing campaign. The first printings of the book included a form on which children could write essays of 25 words or less saying why they thought Chick must be either male or female. A reproduction of one of those now-rare contest forms appears in the new Hungry Tiger Press edition of John Dough. The newspapers that serialized the tale encouraged contest entries with ads like the one above.

And the outcome? According to Baum's son, Frank Joslyn Baum, the contest ended with the awarding of two prizes: one to a girl who said Chick was a girl, and one to a boy who said Chick was a boy. The younger Baum's biography isn't always reliable, but that sounds just like something his father would do.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:31 AM

7

comments

![]()

The Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a type L. Frank Baum returned to in several of his other fantasy stories: a big, carnivorous beast who looked frightening but was a real sweetie underneath. At the end of Wizard, the Lion has gained courage and is once again king of beasts, but what's interesting about that? Starting with Ozma of Oz (1907), Baum made the Cowardly Lion cowardly again, or at least fearful, and for good measure added a Hungry Tiger too troubled by his conscience to eat the fat babies he craves.

In John Dough and the Cherub, published between those two Oz books, the fearsome-looking animal is named Para Bruin. John Dough and his young friends meet Para on an island dominated by primitive imps called Mifkets. Here's the scene:The bear was fat and of monstrous size, and its color was a rich brown. It had no hair at all upon its body, as most bears have, but was smooth and shiny. He gave a yawn as he looked at the new-comers, and John shuddered at the rows of long, white teeth that showed so plainly. Also he noticed the fierce claws upon the bear's toes, and decided that in spite of the rabbit's and the Princess' assurances he was in dangerous company.

Para's remark about the Mifkets' discovery inspired John R. Neill's endpapers illustration for John Dough. He drew a scene of the imps stretching Para across the breadth of the book--a scene that doesn't appear in the story and must take place before it.

Indeed, although Chick laughed at the bear, the gingerbread man grew quite nervous as the big beast advanced and sniffed at him curiously--almost as if it realized John was made of gingerbread and that gingerbread is good to eat. Then it held out a fat paw, as if desiring to shake hands; and, not wishing to appear rude, John placed his own hand in the bear's paw, which seemed even more soft and flabby than his own.

The next moment the animal threw its great arms around the gingerbread man and hugged him close to its body.

John gave a cry of fear, although it was hard to tell which was more soft and yielding--the bear's fat body or the form of the gingerbread man.

"Stop that!" he shouted, speaking in the bear language. "Let me go, instantly! What do you mean by such actions?"

The bear, hearing this speech, at once released John, who began to feel of himself to see if he had been damaged by the hug.

"Why didn't you say you were a friend, and could speak my language?" asked the bear, in a tone of reproach.

"You knew well enough I was a friend, since I came with the Princess," retorted John, angrily. "I suppose you would like to eat me, just because I am gingerbread!"

"I thought you smelled like gingerbread," remarked the bear. "But don't worry about my eating you. I don't eat."

"No?" said John, surprised. "Why not?"

"Well, the principal reason is that I'm made of rubber," said the bear.

"Rubber!" exclaimed John.

"Yes, rubber. Not gutta-percha, you understand, nor any cheap composition; but pure Para rubber of the best quality. I'm practically indestructible."

"Well, I declare!" said John, who was really astonished. "Are your teeth rubber, also?"

"To be sure," acknowledged the bear, seeming to be somewhat ashamed of the fact; "but they appear very terrible to look at, do they not? No one would suspect they would bend if I tried to bite with them."

"To me they were terrible in appearance," said John, at which the bear seemed much gratified.

"I don't mind confiding to you, who are a friend and speak my language," he resumed, "that I am as harmless as I am indestructible. But I pride myself upon my awful appearance, which should strike terror into the hearts of all beholders. At one time every creature in this island feared me, and acknowledged me their king, but those horrid Mifkets discovered I was rubber, and have defied me ever since."

Here's half of that picture, as it appears in my Reilly & Britton copy of John Dough: The right endpaper shows the other half of this scene. To obtain the whole image, you either need to track down an old Reilly & Britton/Lee copy of John Dough and the Cherub, or order the new Hungry Tiger Press edition.

The right endpaper shows the other half of this scene. To obtain the whole image, you either need to track down an old Reilly & Britton/Lee copy of John Dough and the Cherub, or order the new Hungry Tiger Press edition.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:46 AM

0

comments

![]()

Showing a fine sense of priorities, this year's Harvard class got to hear from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke at Class Day exercises and author J. K. Rowling during their more formal commencement. From her remarks: Delivering a commencement address is a great responsibility; or so I thought until I cast my mind back to my own graduation. The commencement speaker that day was the distinguished British philosopher Baroness Mary Warnock. Reflecting on her speech has helped me enormously in writing this one, because it turns out that I can’t remember a single word she said. This liberating discovery enables me to proceed without any fear that I might inadvertently influence you to abandon promising careers in business, law or politics for the giddy delights of becoming a gay wizard.

She went on to speak about poverty versus failure, her work at Amnesty International, and lifelong friendships. I suspect her speech will in fact be memorable.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Edward Bok was without doubt the leading magazine editor in America. Born in Holland in 1863, he had come to America as a child, entered publishing, and taken the reins of The Ladies' Home Journal at the age of 26.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Edward Bok was without doubt the leading magazine editor in America. Born in Holland in 1863, he had come to America as a child, entered publishing, and taken the reins of The Ladies' Home Journal at the age of 26.

By filling that magazine with a not-unfamiliar combination of advice, practical and moral; contests; and celebrity names, Bok pushed its circulation to record numbers. It was the first magazine in the world with more than a million subscribers. (The picture of Bok here comes courtesy of the Historic Bok Sanctuary, an elaborate public garden in Florida that he helped to establish after retiring from being a famous editor and becoming a famous author.)

When I say "celebrity names," I don't mean Bok traded in gossip. Rather, in those pre-broadcasting days, the Ladies' Home Journal and similar magazines were where middle-class Americans turned for entertaining stories to enjoy at home. Bok pursued big-name authors of both fiction and nonfiction. For example, he commissioned some of Rudyard Kipling's Just-So Stories. Bok paid very well, but he paid only after an author had delivered something he thought was worth publishing.

And that's where L. Frank Baum ran into trouble. Around 1904 he was as hot as he'd ever be, with two nationwide bestsellers (Father Goose and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) and a smash stage show (freely adapted from Wizard). Bok talked to Baum about writing an original fairy tale for The Ladies' Home Journal, floating a figure of $2,500 for serial rights.

Baum responded with "John Dough," about a life-sized gingerbread man brought to life in an American city. Years ago, I had the impression that Baum sent Bok an entire story, most of which he later rewrote. I now think Baum sent only what would become the first four chapters of John Dough and the Cherub. My study of his manuscript for The Magic of Oz indicates that Baum rewrote as little as possible.

Bok looked at that story and felt it needed significant rewriting. In particular, he suggested that Baum should include a child character for young readers to relate to. Indeed, the first four chapters of John Dough contain only one child, and not a very sympathetic one.

I think the irony of the situation is that Baum had probably written while thinking of Bok's typical readers: contemporary American homemakers. John Dough starts out in a small bakery and then moves to the streets of an American city, places that Ladies' Home Journal readers would have known well. Two of the strongest characters in those first chapters are the baker's wife and a housewife who thinks the gingerbread man is just right for eating. In the introduction to the new edition of John Dough I note other ways that Bok's magazine might have influenced Baum's creation.

After Bok turned down "John Dough" in its current form, Baum put it aside and nursed his grievances for a while. Eventually he went back and resumed the story in a more fantastic and broadly comical vein. Baum even added the child Bok recommended, one whom both sexes might relate to: the genderless Chick the Cherub. But he never sent it to Bok again; instead, he offered it to the more malleable small publishing firm of Reilly & Britton. John Dough left America and the Ladies' Home Journal world behind forever.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:18 AM

0

comments

![]()

I’ve had a draft of this posting on my Blogger site since November 2006, and the publication of the Hungry Tiger Press edition of John Dough and the Cherub spurred me to finish it.

I’ve had a draft of this posting on my Blogger site since November 2006, and the publication of the Hungry Tiger Press edition of John Dough and the Cherub spurred me to finish it.

In researching the introduction for that edition, I dug into the folktale that obviously inspired L. Frank Baum to write that novel: the story of the Gingerbread Man. That’s a version of the tale called “The Runaway Pancake,” classified by folklore scholars as Aarne-Thompson type 2025. Examples have been documented in many European cultures, from Ireland to Russia, Norway to Slovenia. (See Prof. D. L. Ashliman's folktexts website for examples of other widespread tales.)

As I understand it, one basis of the study of folklore is that the more widespread a story or motif within a story is, the older it probably is. Conversely, a variation on a story or song that shows up in only a few collected versions is more likely to be a recent creation or addition.

The story of the gingerbread man provides an interesting case study for those guidelines. “The Runaway Pancake” is widespread enough that it must be quite old. In most cases the runaway breadstuff is simpler than a gingerbread man: it’s a “thick, fat pancake” in the earliest printed version (from Germany in 1854), a “wee bunnock” in an early Scottish version, a johnny-cake in a tale from the American South. Gingerbread shaped like a human entered the scene in St. Nicholas magazine in 1875; while that’s an early printed example of the tale, the gingerbread is rare in other versions, indicating it was a recent ingredient.

All the versions of “The Runaway Pancake” have the same middle of the story: the breadstuff rolls or runs away from the people who made it. They give chase, joined by other people and animals. The pancake taunts an increasingly long list of pursuers.

The versions diverge at the ending. In some tales, a wily animal--a fox, a pig--fools the pancake into coming too close, and then gobbles it up. (The picture above, from Joseph Jacobs’s More English Fairy Tales of 1894, shows a fox feigning deafness so Johnny-Cake comes closer.) One version of the story has a fox offering to carry the gingerbread man across a river and gobbling him up on the way.

The variations I find most interesting are those that hint at why a pancake or gingerbread man would up and move in the first place. Sometimes it just doesn't want to be eaten. Other versions offer different explanations with implied moral lessons.

The St. Nicholas retelling, which was printed syllable by syllable for young children to sound out, starts like this: There was once a lit-tle old man and a lit-tle old wom-an, who lived in a lit-tle old house in the edge of a wood. They would have been a ver-y hap-py old coup-le but for one thing,--they had no lit-tle child, and they wished for one ver-y much. One day, when the lit-tle old wom-an was bak-ing gin-ger-bread, she cut a cake in the shape of a lit-tle boy, and put it into the ov-en.

That version implies that the old woman’s wish for a child was so strong it brought the gingerbread to life. For wanting what she can’t have, she has to chase after her gingerbread, and never catches it.

Pres-ent-ly she went to the ov-en to see if it was baked. As soon as the ov-en door was o-pened, the lit-tle gin-ger-bread boy jumped out, and be-gan to run a-way as fast as he could go.

“Johnny-Cake,” documented in the American South in 1889, starts like this: Once upon a time there was an old man, and an old woman, and a little boy. One morning the old woman made a Johnny-Cake and put it in the oven to bake.

Here the runaway breadstuff becomes a lesson for children about carelessness.

“You watch the Johnny-Cake while your father and I go out to work in the garden.”

So the old man and the old woman went out and began to hoe potatoes and left the little boy to tend the oven. But he didn’t watch it all the time, and all of a sudden he heard a noise, and he looked up and the oven door popped open, and out of the oven jumped Johnny-Cake and went rolling along end over end towards the open door of the house.

And way back in that German “Thick, Fat Pancake” of 1854, the ending is: Then three children came by. They had neither father nor mother, and they said, “Dear pancake, stop! We have had nothing to eat the entire day!” So the thick, fat pancake jumped into the children’s basket and let them eat it up.

Once again, there’s a clear moral--but that appears to be a late addition to the tale.

All those variations make me think that the oldest, central part of the story is the pursuit of the pancake or gingerbread man, and his taunting chant at the pursuers. Over the centuries, storytellers in different cultures added different details to explain that core story and invest it with a moral meaning.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:45 AM

3

comments

![]()

This will be JOHN DOUGH WEEK at Oz and Ends, celebrating the arrival of the 102nd-anniversary edition of L. Frank Baum's John Dough and the Cherub from Hungry Tiger Press. Yes, it's fully baked at last!

This will be JOHN DOUGH WEEK at Oz and Ends, celebrating the arrival of the 102nd-anniversary edition of L. Frank Baum's John Dough and the Cherub from Hungry Tiger Press. Yes, it's fully baked at last!

L. Frank Baum started to write John Dough on spec for Edward Bok, editor of The Ladies' Home Journal, as I'll discuss later in the week. After Bok declined to publish the story, Baum rethought and finished it for the publishing firm of Reilly & Britton, founded to issue his Marvelous Land of Oz in 1904. As with Land, Reilly & Britton commissioned John R. Neill to illustrate the book. Baum, Neill, and the firm went on to collaborate on twelve more Oz novels and many other books.

The first printings of John Dough had three-color artwork: black, red, and either yellow, green, or blue, depending on the signature. Eventually Reilly & Britton (which became Reilly & Lee) stopped printing the colored inks, and sometime in the mid-1900s let the book go out of print.

John Dough was unavailable for decades. In 1966, March Laumer's Opium Press in Hong Kong issued a small edition with new illustrations in a modern cartoony style by Lau Shiu Fan. Then in the 1970s Dover released a paperback reprint of the first printing with an introduction by Martin Gardner; that's how I first read the book. That paperback went out of print years ago. Project Gutenberg makes the text of John Dough available for free, but Neill's delightful artwork has not been republished in years.

The new Hungry Tiger Press edition of John Dough and the Cherub offers these features:

Finally, while this edition doesn't include the insights of Martin Gardner, you get to read me discoursing on the book's historical roots and narrative structure. I used some of that material in a 2006 article for The Baum Bugle, but other parts are available only in the introduction to this Hungry Tiger Press edition.

PERMANENT LINK:

12:07 PM

5

comments

![]()

Today I'll link to John Hodgman's long review in yesterday's New York Times Book Review of three notable epics in comics form:

Today I'll link to John Hodgman's long review in yesterday's New York Times Book Review of three notable epics in comics form:

I’ll add a confession that goes against the grain of most comics criticism: I never much liked Jack Kirby’s art.

I can see how Kirby’s early work on Captain America with Joe Simon reinvigorated the action-comics form. I admire the length and breadth of his career. I marvel at his vast capacity for work. I appreciate how much Kirby did to invent the “Marvel universe” with Stan Lee in the 1960s. But when I read his 1960s superhero comics as a teenager, most of the faces looked the same, the lines seemed thick and bombastic, and I preferred other artists’ books. (I've come to like Kirby's earlier work more.)

And honestly--naming a character “Scott Free”?

It's like Hemingway, I guess. The man is obviously the most influential American novelist of his generation, greatly changing the style of popular prose (for the better, mostly). That doesn't mean I have to enjoy his novels.

PERMANENT LINK:

3:37 PM

0

comments

![]()

One of the visual techniques of comics that I find most interesting is a sequence of similar panels. I'll explain what I mean with help from--who else?--Robin the Boy Wonder.

It's relatively rare to find such repetitive images in modern picture books because that form has come to emphasize visual variety and richness, usually just one full-spread image at a time. The technique depends on the readers' eyes quickly comparing two juxtaposed images, which is harder with a page turn in between. There are exceptions to that rule, of course; Ellen Raskin was a master at producing meaning from repetitive illustration, spread to spread.

One version of this technique is to show several instants in one scene from the same angle, with the same framing and the same background. That directs our eyeballs to what changes from one image to the next, usually the characters in action. This sequence of panels featuring the current Robin, Tim Drake, comes from Robin Plus Fang, script by Chuck Dixon, art by Anthony Williams and Andy Lanning.

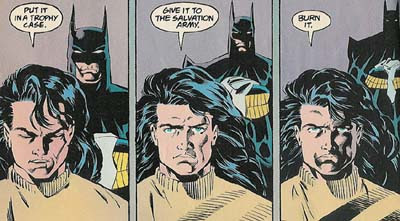

The changes in similar panels don't have to be so physical, though. Here's a sequence from the first Nightwing miniseries, collected in Ties That Bind, by Dennis O'Neil and Greg Land. Dick Grayson has decided to get out of the vigilante business. (I suspect that his hair was taking up a lot more of his time than he'd expected.) He's telling Batman what to do with his costume.

With each panel, Dick's face grows darker, and the Batman more distant. The similar but changing images convey the protagonist's mood.

With each panel, Dick's face grows darker, and the Batman more distant. The similar but changing images convey the protagonist's mood.

Repetitive images can also focus our attention on one changing detail which might otherwise be lost, such as the grin that appears on "Batman's" face in the second panel below. That's all the clue that Nightwing needs, trained detective that he is.

That sequence is from JLA/The Titans: The Technis Imperative, by Devin Grayson and Phil Jimenez.

That sequence is from JLA/The Titans: The Technis Imperative, by Devin Grayson and Phil Jimenez.

Repetitive images are also a tool for pacing. Seeing two similar panels, especially with no word balloons, tells us that time passes even when we don't see change. In the next sequence, Batman asks the third Robin, Jason Todd, to explain what happened to the rape suspect who was just with him on that balcony.

Batman's figure stays the same, so we sense he's waiting and waiting for an answer. These panels are from Batman, #424, script by Jim Starlin, art by Mark "Doc" Bright and Steve Mitchell.

Batman's figure stays the same, so we sense he's waiting and waiting for an answer. These panels are from Batman, #424, script by Jim Starlin, art by Mark "Doc" Bright and Steve Mitchell.

Given how repetitive panels affect pacing, they can also be used for comic effect. After all, what's the key to comedy?

Timing. In the next sequence, the adult mentor of the teen-aged superhero group Young Justice orders Tim Drake as Robin and his speedy friend Impulse not to search for their missing comrade Secret.

This page comes from an uncollected issue of Young Justice, script by Peter David and drawing by Todd Nauck.

This page comes from an uncollected issue of Young Justice, script by Peter David and drawing by Todd Nauck.

The brief, silent passage of time created by wordless panels in each of the last three examples is the equivalent of what screenwriters have come to call a beat. Such a silence can be hard to convey in prose, and The New Yorker has caught some lazy novelists instructing readers that characters "waited a beat" before they speak.

The visual dimension of comics makes it easy to convey that silent moment. Here's yet another example, from the current teen-superhero magazine to feature Robin, the third volume of The Teen Titans.

This deathless conversation was published in the volume Teen Titans/Outsiders: The Insiders. Scripted by Geoff Johns, penciled by Matthew Clark, inked by Art Thibert.

This deathless conversation was published in the volume Teen Titans/Outsiders: The Insiders. Scripted by Geoff Johns, penciled by Matthew Clark, inked by Art Thibert.

That last example also hints at something I don't like about how comics artists are applying this technique today. Many artists now work on computers ("penciled" and "inked" are just digital metaphors). That makes it awfully tempting to copy and paste an image from one panel to the next, especially when working under a tight deadline. The three-panel sequence of Nightwing and his hair far above is obviously hand-drawn, and the artists made many changes, large and subtle, from one panel to the next. But the two images of Robin above are identical down to the cross-hatched shadows and coloration.

A growing number of copy-and-paste jobs strike me as having been done without enough regard for the dramatic needs of the scene. This last example comes from Outsiders: Looking for Trouble, script by Judd Winick, art by Todd Raney and Scott Hanna. In these panels, it makes sense to draw the redhead the same because he's making a deadpan joke. His expression shouldn't change. But doing the same for Nightwing just looks like laziness. And using the same image for two panels with different characters talking apparently means that neither can be shown with his mouth open.

The only place I enjoy watching cardboard cutouts talk to each other like that is Wondermark.

The only place I enjoy watching cardboard cutouts talk to each other like that is Wondermark.

J. L. BELL is a writer and reader of fantasy literature for children. His favorite authors include L. Frank Baum, Diana Wynne Jones, and Susan Cooper. He is an Assistant Regional Advisor in the Society of Children's Book Writers & Illustrators, and was the editor of Oziana, creative magazine of the International Wizard of Oz Club, from 2004 to 2010.

Living in Massachusetts, Bell also writes about the American Revolution at Boston 1775.