The 99’s Name Is Legion

The Atlantic Monthly is devoting a lot of pixels and ink to The 99, a comic book about young Muslim superheroes. In addition to the print article, there’s a slide show of characters and an interview with creator Dr. Naif al-Mutawa.

The Atlantic Monthly is devoting a lot of pixels and ink to The 99, a comic book about young Muslim superheroes. In addition to the print article, there’s a slide show of characters and an interview with creator Dr. Naif al-Mutawa.

The 99’s website offers a free download of the series’s “Origins” issue, written by Mutawa and Fabian Nicieza (who has once again taken up the mantle of writing former Robin Tim Drake for DC Comics). That issue also shows the emergence of one young hero, but eventually the series promises ninety-nine, each with a distinct power.

Which makes me think that Dr. Al-Muttawa has basically reinvented DC’s Legion of Super Heroes. Originally conceived for a Superboy story, this is a group of young people from the future who develop various powers and band together to fight…well, that varies somewhat depending on which “continuity” one reads. As does the lineup of heroes, beyond a core handful.

The 99 offers some innovations, to be sure. One character appears to be a superpowered grant writer. And the kid with circuit lines on his face? He’s not green like Brainiac 5. Most significant to its launch, all of the 99 are Muslim; each is supposed to represent a different Islamic virtue. Though those virtues look very much like the virtues of other belief systems.

In one way, this approach is a good fit for the symbolic nature of modern superheroes, as Douglas Wolk discusses in Reading Comics. Each character offers a chance to explore what his or her defining power and virtue mean. In practice, however, The 99 faces some big storytelling challenges.

One is that such a large group presents too many heroes for most readers to track. The Legion of Super Heroes has the same problem. Some fans argue that its characters are simple to keep straight since their professional names state their powers: Lightning Lad, Triplicate Girl, Invisible Kid, Bouncing Boy, Shadow Lass, and so on. That worked fine back when the comics showed them addressing each other by those names every other balloon. Now, in the cause of realism, stories show more of the characters’ private lives, and they address each other by their given names. For most readers a new Legion issue is like tuning into a long-running soap opera they’ve never watched before.

For its established fans, in fact, the Legion’s size appears to be a plus. They apparently go gaga over pictures of the whole group, judging by the number of images available. Can The 99 build to that level of following without half a century of gradual growth?

The second challenge is the tension between collective and individual heroism. Al-Muttawa is trying to make a point about worldwide unity. He sends his characters out on adventures in teams of three or four. (Batch-processing seems inevitable when you’ve got ninety-nine heroes to introduce.) Though readers might identify with favorites, they’re supposed to follow the entire group.

But superhero fans the world over might be seeking a different sort of story. The Atlantic found a “a 36-year-old [Muslim] filmmaker, photographer, and comic-book enthusiast” who said he’s looking for something else:

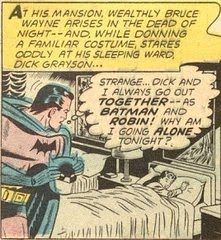

“I like the image Dr. Naif is bringing with The 99, but unfortunately it’s not very successful here,” he said. Al-Duwaisan still preferred his Batmans to The 99—and not because of too little Islamic subtext, but too much. Al-Duwaisan felt that groups of heroes working collectively missed the very point of the Western comics he adores: the triumph of the individual.

“In the West, there’s one hero,” he said with visible longing. “If there are too many of them, you can’t idolize anyone. I don’t feel the heroism. I am reading Batman because I see part of myself in it.”

Last month master comics letterer

Last month master comics letterer