Yesterday I quoted Elaine Dundy’s 1985 book Elvis and Gladys on Elvis Presley's admiration for the comic-book hero Captain Marvel, Jr., one of the Shazam! family. Presley liked that character so much, Dundy wrote, that he adopted Junior's look, his behavior, and his symbols.

What led Dundy to that conclusion? As I noted yesterday, her book didn't quote Presley or his friends speaking of a special connection to Junior, nor point to comic books that Presley had saved featuring the character.

Dundy has since explained how she made the link on her website:

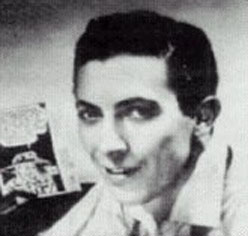

Back in London where I was living at the time I did some sleuthing on my own. Elvis was often quoted as saying that he was the hero of every comic book he'd read. One day I sat down in a Comics bookshop to look at those popular when he was growing up. I looked at all those double identity heroes he must have read from Superman to the Spirit. Then I came across Elvis’ face staring at me from its pages: It was the face of Captain Marvel Jr.

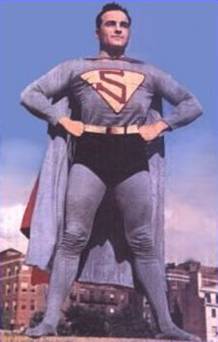

So Dundy started with a general quote from Presley about comics ("hero of every comic book") and her psychological theory about what haunted the singer ("all those double identity heroes"). She then singled out one particular character as Presley's childhood favorite because of his physical resemblance to Presley as an adult--after the man had dyed his hair black, grown sideburns, and started wearing jumpsuits and capes on stage.

Thus, Presley's later appearance was Dundy's evidence that Captain Marvel, Jr., was his favorite, and Captain Marvel, Jr., being his favorite was Dundy's explanation for his later appearance. That's circular reasoning, as well as an example of the common fallacy

post hoc, ergo propter hoc. There's still no real evidence of a connection.

In

Elvis and Gladys, Dundy didn't lay out that reasoning process. Instead, she simply stated many times, with no hint of doubt, that Junior was Elvis Presley's favorite comic-book hero and model for life. And those statements have been picked up and repeated uncritically by other writers since.

It's very likely that Presley read about Captain Marvel, Jr., as a boy. The Shazam! comics were among the most popular in the country, especially the Midwest, where the Fawcett company was

located founded. But he read apparently a lot of other comics, too.

Presley did take to wearing capes in the last years of his career. But so did many other performers of the same period: Jimi Hendrix, Roger Daltrey, James Brown, Rick Wakeman, ? of the Mysterians, and so on. And of course the Shazam! family weren't the only comic-book heroes who wore capes. Many other favorites did as well.

Yet another supposed piece of evidence is how Presley adopted a lightning bolt symbol for his "TCB" crew. The Shazam! family got their powers when lightning bolts struck. However, there are

many explanations for Presley's symbol, some with

supporting documentation or

first-hand memories instead of speculation.

In expounding on Dundy's hypothesis, Robby Reed at

Dial B for Blog quoted Presley's cousin and personal assistant

Billy Smith on the Shazam! connection:

- “If you go back and look at a drawing of Captain Marvel Jr., it looks a whole lot like the seventies Elvis--one-piece jumpsuit, wide belt, boots, cape, lightning bolt and all.”

- “One of the comics Elvis read when he was a kid was Captain Marvel Jr. He went after Captain Nazi during WWII. And he had this dual image--normal, everyday guy and super crime-fighter. Sounds like Elvis, don’t it?”

- “The lightning bolt came from his army days. It was the insignia of his battalion. Or maybe in the back of his mind, he identified it with Captain Marvel Jr. That’s where he got the idea for the capes. From the comic books.”

The first two quotations are general observations of similarity--the same "evidence" that Dundy relied on. The third actually states

another source for Presley's TCB symbol, mentioning comic books only as a possibility, and in an afterthought. Surely if Presley had displayed a particular interest in Junior, then Smith--a cousin who grew up with him and then worked for him--would have more evidence to share than that.

Reed's web essay didn't cite a source for those Smith quotes. I’d like to know whether they predated Dundy’s 1985 book, which has been influential in molding the public's understanding of Presley. Graceland and other tourist sites devoted to him now display comic books featuring Captain Marvel, Jr. Only the curatorial records could say for sure, but I suspect those copies were bought from dealers to reflect what Dundy wrote rather than plucked out of Presley's own collection--that the "evidence" was gathered to support the theory rather than the theory developed from hard evidence.

This is the

This is the  When the London Eye was built for the millennium celebrations (remember those?), it was considered a temporary structure. However, like the Eiffel Tower, it's proven so popular and iconic that no one's talking about taking it down anymore.

When the London Eye was built for the millennium celebrations (remember those?), it was considered a temporary structure. However, like the Eiffel Tower, it's proven so popular and iconic that no one's talking about taking it down anymore. Each of those pods can hold 20-30 people, and the wheel rotates slowly but continuously. Entering or exiting a pod is therefore rather like stepping on or off an escalator.

Each of those pods can hold 20-30 people, and the wheel rotates slowly but continuously. Entering or exiting a pod is therefore rather like stepping on or off an escalator.

Presley did take to wearing capes in the last years of his career. But so did many other performers of the same period: Jimi Hendrix, Roger Daltrey, James Brown, Rick Wakeman, ? of the Mysterians, and so on. And of course the Shazam! family weren't the only comic-book heroes who wore capes. Many other favorites did as well.

Presley did take to wearing capes in the last years of his career. But so did many other performers of the same period: Jimi Hendrix, Roger Daltrey, James Brown, Rick Wakeman, ? of the Mysterians, and so on. And of course the Shazam! family weren't the only comic-book heroes who wore capes. Many other favorites did as well.