The Real Story of Horton the Elephant

When Dr. Seuss was asked about the genesis of his 1940 picture book, Horton Hatches the Egg, he usually told some variation on the story quoted here at Mental Floss:

When it comes to Horton Hatches the Egg, Cohen shows that:

The really significant changes are that all those previous cartoons and stories had been for adult audiences, and almost all presented the odd mammal as misguided rather than heroic. The egg-sitting walrus was part of “The Truly-Dumb Animal Shoppe”; the first winged elephants were the product of delirium tremens; the elephant from 1934 cracked the egg’s shell.

As for Matilda, she managed to hatch the chickadee, but it took one look at her, “cried out in terror,…and flapped off frantically.” The moral of that story is: “Don’t go around hatching other folks’ eggs.” That, of course, is quite a different outcome from Horton’s pride at hatching an elephant-bird.

When Dr. Seuss went back to that idea as a recently-hatched children’s-book author, he was able to embrace the nonsense of the image of an elephant in a nest in a tree and create an ending that adults might know is unreal but which rewards Horton. For young readers, Dr. Seuss took his old elephant who defied convention and made him heroic rather than pathetic.

The Seuss, the Whole Truth, and Nothing But the Seuss analyzes other oft-told aspects of Dr. Seuss’s life as well, such as when and why he adopted pseudonyms and the critical response to The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. It’s worth a look.

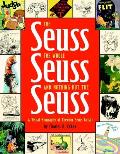

I was in my New York studio one day, sketching on transparent tracing paper, and I had the window open. The wind simply took a picture of an elephant that I’d drawn and put it on top of another sheet of paper that had a tree on it. All I had to do was to figure out what the elephant was doing in that tree.Charles D. Cohen’s “visual biography” of Seuss is titled The Seuss, the Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss in part, I suspect, because it seeks to get to the truth behind such anecdotes.

When it comes to Horton Hatches the Egg, Cohen shows that:

- Seuss had drawn a whale up a tree for Judge magazine in 1927, a dachshund hatching a stork’s egg for Life in 1929, and a walrus hatching eggs in a tree for Judge in 1931.

- He had drawn elephants with wings for Life in 1930 and a book called Spelling Bees in 1937.

- He had drawn an elephant sitting on an egg for Life in 1934.

The really significant changes are that all those previous cartoons and stories had been for adult audiences, and almost all presented the odd mammal as misguided rather than heroic. The egg-sitting walrus was part of “The Truly-Dumb Animal Shoppe”; the first winged elephants were the product of delirium tremens; the elephant from 1934 cracked the egg’s shell.

As for Matilda, she managed to hatch the chickadee, but it took one look at her, “cried out in terror,…and flapped off frantically.” The moral of that story is: “Don’t go around hatching other folks’ eggs.” That, of course, is quite a different outcome from Horton’s pride at hatching an elephant-bird.

When Dr. Seuss went back to that idea as a recently-hatched children’s-book author, he was able to embrace the nonsense of the image of an elephant in a nest in a tree and create an ending that adults might know is unreal but which rewards Horton. For young readers, Dr. Seuss took his old elephant who defied convention and made him heroic rather than pathetic.

The Seuss, the Whole Truth, and Nothing But the Seuss analyzes other oft-told aspects of Dr. Seuss’s life as well, such as when and why he adopted pseudonyms and the critical response to The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. It’s worth a look.

1 comment:

Ha! Nice turn on the old "Where do you get your ideas?" ... Reminds me of the Baum story about where he came up with the origin of Dorothy's oldest Oz friend, the Scarecrow. The Scarecrow appeared in a nightmare; Baum switched the figure from one of menace to one of innocence. I think that's a believable origin for many an idea - taking a familiar element and switching the expectations around it.

The random juxtaposition of images can also be a good source. I suspect Seuss consciously did that, too, if, perhaps, in other circumstances.

Post a Comment