Illustrating Picture Books versus Drawing Comics

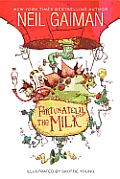

Toward the end of his conversation with Skottie Young on the Stuff Said podcast, artist Gregg Schigiel asks about Young’s experience illustrating his first picture book, Fortunately, the Milk by Neil Gaiman. (A lot of Schigiel’s interviews seem to be digging for career counseling, but that’s another story.)

Young sounds almost amazed as he reports how much easier illustrating a picture book was compared to drawing a comic. Jef Czekaj said the same thing on a panel I moderated a while back. I wouldn’t be surprised if other artists who’ve worked in both fields feel the same way. That’s not to say picture-book illustration is easy; but relatively it seems to be a more pleasant experience.

For one thing, picture books don’t require so many pictures. A 32-page picture book might require 20 separate images, which could fill as few as four pages of standard comics. True, those images have to be bigger and more detailed so that they reward multiple readings. On the other hand, they don’t have to be so tightly squeezed together on a page with captions and word balloons impinging on them.

More important, however, is how picture-book publishers treat artists. Editors and art directors choose an artist based on his or her past work and reputation, and they see their job as assisting the writer’s and artist’s visions come to fruition, not to move the corporation’s larger story along. They don’t try to exercise so much editorial control. They set more generous deadlines.

Schigiel’s book experience has come with licensed titles (i.e., those that are part of a corporation’s larger story). So he starts out asking Young what his Art Director told him. But Art Directors for picture books are far more hands-off than people with the same title in other parts of publishing. Young found himself surprised at how few “notes” he received back on his sketches.

The biggest difference between the mainstream book business and other forms of publishing is visible on the covers. On a book, the author’s and illustrator’s names are almost always the biggest; on Fortunately, the Milk, Gaiman’s name is huge, Young’s rather small. But the publisher’s name is usually smallest of all, slipped onto the bottom of the spine and the back. In a comic book or other magazine, the magazine’s name is the biggest; its employees are in charge, and its intellectual property and reputation is what mainly drives the sales.

Young sounds almost amazed as he reports how much easier illustrating a picture book was compared to drawing a comic. Jef Czekaj said the same thing on a panel I moderated a while back. I wouldn’t be surprised if other artists who’ve worked in both fields feel the same way. That’s not to say picture-book illustration is easy; but relatively it seems to be a more pleasant experience.

For one thing, picture books don’t require so many pictures. A 32-page picture book might require 20 separate images, which could fill as few as four pages of standard comics. True, those images have to be bigger and more detailed so that they reward multiple readings. On the other hand, they don’t have to be so tightly squeezed together on a page with captions and word balloons impinging on them.

More important, however, is how picture-book publishers treat artists. Editors and art directors choose an artist based on his or her past work and reputation, and they see their job as assisting the writer’s and artist’s visions come to fruition, not to move the corporation’s larger story along. They don’t try to exercise so much editorial control. They set more generous deadlines.

Schigiel’s book experience has come with licensed titles (i.e., those that are part of a corporation’s larger story). So he starts out asking Young what his Art Director told him. But Art Directors for picture books are far more hands-off than people with the same title in other parts of publishing. Young found himself surprised at how few “notes” he received back on his sketches.

The biggest difference between the mainstream book business and other forms of publishing is visible on the covers. On a book, the author’s and illustrator’s names are almost always the biggest; on Fortunately, the Milk, Gaiman’s name is huge, Young’s rather small. But the publisher’s name is usually smallest of all, slipped onto the bottom of the spine and the back. In a comic book or other magazine, the magazine’s name is the biggest; its employees are in charge, and its intellectual property and reputation is what mainly drives the sales.

No comments:

Post a Comment