Why Dick Grayson as Batman Reached a Dead End

If we can interpret the sagas of, say, Wally West and Stephanie Brown in the 1986-2011 DC Comics universe as successful and complete coming-of-age stories, can we do the same for their contemporaries Dick Grayson and Tim Drake? And what does that mean for the new manifestations of those characters in the company’s new continuity?

If we can interpret the sagas of, say, Wally West and Stephanie Brown in the 1986-2011 DC Comics universe as successful and complete coming-of-age stories, can we do the same for their contemporaries Dick Grayson and Tim Drake? And what does that mean for the new manifestations of those characters in the company’s new continuity?

Although DC’s editors have promised fans that little had changed in the Batman saga, there were significant changes to both Dick and Tim in the transition. Ironically, Tim underwent more outward changes than Dick, but his overall character storyline has remained much the same while Dick’s shifted significantly.

The last issues of the old Red Robin and Teen Titans magazines left Tim as Red Robin, a step away from his first crime-fighting identity as Robin but not yet fully his own man. He was back living in Wayne Manor; indeed, he was more involved with Bruce Wayne’s business than any other adopted son.

As usual, Tim was smart, serious, and fretful about living up to the challenge at hand. Since his first appearance in 1989, he’s been unusually mature for his age, preserving his father figures from their faults. But he remained an adolescent.

Indeed, when Bruce Wayne appeared to be dead, Tim alone rejected that idea. He turned out to be right, of course, but that also showed how he wasn’t ready to go on without his father-figure, that in his saga he didn’t come of age yet. To the premature end, Tim was still working through the issues of being an adolescent hero. His unresolvable foundational conflict was still trying to grow up without becoming too dark.

Despite those changes, Tim’s overall story is still about coming of age. He’s still worried about maintaining the best parts of the bat-tradition without becoming cruel. As founder of this universe’s first Teen Titans, he’s at the center of its symbolic generational struggle.

In contrast, in the 1986-2011 DC Universe, Dick Grayson did come of age. He became Batman, not just temporarily but permanently (at least as he and most characters believed). The “man” in that crime-fighting name signaled his fully mature status.

Unfortunately, that transition left Dick without an unresolvable foundational conflict. Once he confirmed his ability to be Batman without losing himself, that conflict was resolved. And that left no clear way for the character to develop.

Some of the stories told in the last couple of years of that universe, such as Scott Snyder’s Black Mirror, are quite good. But they didn’t grow from Dick’s individual history and qualities. Nor did the company make major changes to that character’s life, such as marriage or another relationship, injury, revelation of secret identity, loss of fortune, move to another city, and so on, which could produce a new overarching challenge. While successful in both fictive life and sales, the character of Dick Grayson had reached a dead end. On top of that, the return of Bruce Wayne from the past meant the company had two Batmen at once, and that was confusing for everyone.

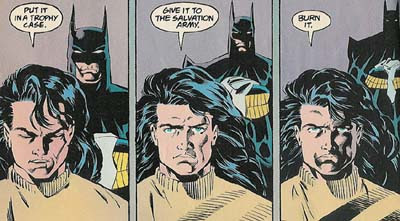

The last time that Dick stepped back after being Batman, in the 1994 issues collected in Prodigal, he told Bruce that he felt he’d failed as a hero and was ready to give up costumes and retire.

This attitude seems uncharacteristic, and of course it didn’t last. But from a creative standpoint that moment reveals the difficulty of shifting Dick back to the role he adopted as an older adolescent without acknowledging that it looks like a step backward.

So this time DC simply skipped that transition. The new universe’s Dick Grayson was introduced younger than before and back in a Nightwing costume. Though he’s stood in for Batman at least once, that history seems to a minor part of his past. The stories once again focus on Dick figuring out his role in life, just as they have since the 1980s. Once more, he’s coming of age.

Thus, we can read the Dick Grayson saga from 1986 to 2010 as a successful coming-of-age, but one that left a lot more unanswered questions that Wally West’s growth to a family man or Stephanie Brown’s achievement of respect. And the new Dick Grayson saga dialed back to odometer and started that story again, with the same foundational conflict as before. Does that feel like a loss to the characters’ fans? Probably so, but it’s also a restoration of the character that attracted us in the first place. Because, although we root for Dick Grayson to grow up successfully, he’s not as interesting if he does.

5 comments:

Based on what's happened to Steph and Wally, if we'd like to keep reading Grayson, better hope he never truly matures.

Considering the same question another way, if Dick Grayson were to mature (e.g., marry, have kids, become fully independent of Bruce Wayne), would most of his fans keep reading him?

A lot of the character's symbolic appeal seems to be based on his liminal quality between youth and full-fledged adulthood.

About six years ago, if I recall right, an issue of Flash showed Wally West visiting Titans Tower in San Francisco and contemplating Dick Grayson—his friend who never seemed to change. Unlike all the other original Titans, Dick still wasn't married, still had no kids.

That strikes me as summing up the difference between the two characters in the then-current DC Universe. Wally's path had been a journey, often moving and definitely ending up in a new place. Dick's developments (jobs, love affairs, teams) were all impermanent.

Personally, I think Wally West's character still has a lot of potential as a family man: a speedster trying to get his kids to activities and playdates! But that's not the main demographic that DC Comics is trying to reach. And there's still the question of how many people can inhabit one trademark at one time.

I think the issue I was remembering is Flash, #210.

I tend to find heroes with wives and kids or husbands and kids a lot less interesting. It's mostly due to the limitations of the secondary characters in the hands of most writers, of course.

Also I feel that while Robins may come and go there should only be ONE Nightwing. That *is* his mature identity. He's on the same journey now most readers are: how to prove himself before he dies. I think that's why he's appealing to younger readers and especially to women - not because he's not a full adult, but because there's a false perception of role he'll always be surprising people by moving beyond.

I think we agree that the character of Dick Grayson works best as Nightwing, not Batman, and that his status as a former sidekick is inherent in what his character represents. That and his lack of superpowers leave him having to prove himself differently from other heroes. I also think that brings us back to the unresolvable foundational conflict. Once Dick does prove himself—by being quite successful as Batman, for instance—there's less tension in his overall character development.

For a hero to have a spouse and children obviously changes his or her freedom to dash around anywhere. However, all heroes have some limits, and I think that one could be especially interesting in the case of Wally West, who's grown up able to dash anywhere in a few seconds. But the audience for such stories might not overlap with the majority of readers of American comics today. (Even with Mark Waid scripting, Flash-family stories didn't sell high enough to keep running.) Too much quotidian reality might interfere with the escapism that seems inherent in the genre.

Post a Comment