How Picture Books (and Life) Used to Be

Courtesy of the Albert Whitman blog, a page from Time to Eat: A Picture Book of Foods, by Mame Dentler and Frank Fenner, Jr., published in 1945:

Musings about some of my favorite fantasy literature for young readers, comics old and new, the peculiar publishing industry, the future of books, kids today, and the writing process.

Courtesy of the Albert Whitman blog, a page from Time to Eat: A Picture Book of Foods, by Mame Dentler and Frank Fenner, Jr., published in 1945:

PERMANENT LINK:

12:34 PM

1 comments

![]()

PERMANENT LINK:

5:13 PM

2

comments

![]()

The American Antiquarian Society in Worcester has announced two new short-term fellowships for the study of early American children’s literature:

The Justin G. Schiller Fellowship supports research by both doctoral candidates and postdoctoral scholars from any disciplinary perspective on the production, distribution, literary content, or historical context of American children’s books to 1876.As a teenager, Schiller helped to found the International Wizard of Oz Club, and he went on to become a leading dealer in children’s books.

The Linda F. & Julian L. Lapides Fellowship supports research on printed and manuscript material produced in America through 1865 for (or by) children and youth. The Lapides Fellowship will support projects examining the creative, artistic, cultural, technological, or commercial aspects of American juvenile literature and ephemera produced between the Puritan Era and the Civil War. It is open to both postdoctoral scholars and graduate students at work on doctoral dissertations.The deadlines for applying for either scholarship is 15 Jan 2012. See the AAS website for more details.

The Eloise character herself was totally Kay Thompson. She told me who this little girl was. Kay was not particularly visual, and when we worked together, she would talk to me and I would draw things. And that’s how we did all the books. We worked directly together, which is very unusual.That’s an interesting way to reconsider Eloise—as one of those adult books that look like picture books, but aren’t at all meant for the traditional picture-book readership. Certainly they weren’t created in the typical picture-book way, but that means nothing about the intended audience.

And the other thing that I keep talking about, because Kay was so adamant about it, is that they were never children’s books. They have become children’s books, but Kay never agreed that they were. It was sort of a joke in the beginning. There was a chain of bookstores called Doubleday on Fifth Avenue in New York, and Kay lived nearby at the Plaza. She used to go in and [see that the Eloise books] had been moved into the children’s section. She would march in and carry them to the front of the store and put them in the adult section. And then they’d just get moved back again.

It was the best thing, really, that happened to her because it was kind of a novelty adult book. It even says that it’s not a children’s book; it says that it’s a book for precocious adults in a banner across the top. She never wrote the books down to children. Of course, they look like children’s books and they were about someone who was getting away with something, so it appealed to kids, thank God.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:15 AM

0

comments

![]()

I think the biggest surprise was how professional all the artists were. Not a single submission came in after deadline. Not one. I remember having visions of artists calling at 5:01 asking for extensions, but it was silent, so I played with fonts instead.Giving credit where it’s due, I must report that artist Alex Cormack handled the submission of our story, “Essex County Literary Wax Museum & Menagerie,” which leads off the collection. I might well have been on the phone at 5:01.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:29 AM

0

comments

![]()

We piglets do not all agree.Or maybe that’s in honor of the new Supreme Court session.

Now three of us are saying, “No,”

While “Yes” declare another three,

And three aren’t sure which way to go.

We therefore caucus and discuss

The very best thing to be done,

What holds the most rewards for us,

And tally: four to four to one.

The argument turns fierce and hot

Until the vote is five to four.

At last we’re done! But we forgot

Exactly what we voted for.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:51 AM

0

comments

![]()

PERMANENT LINK:

1:12 PM

0

comments

![]()

PERMANENT LINK:

11:59 PM

0

comments

![]()

Bradamant’s Quest is set in a fantasy world that was immensely popular for centuries, but which we don’t visit much anymore: the “Matter of France,” or romances of Charlemagne. How did you decide to add to that saga? What does it offer that we don’t find in other great myths of the western world?Bradamant’s Quest comes to us from FTL Publications of Minnesota, which offers a free peek at the first chapter.

When I read the stories in the Incompleat Enchanter series by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, many years back, their treatments of the worlds that Harold the I.E. visits made me interested in looking up and reading the books involved. That eventually led me to reading a translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, and I thought Ariosto’s Bradamant was a fascinating character, sure of herself and resourceful in going after her true love (a warrior in the enemy army’s forces? — no reason to give up, is her feeling).

Bradamant gets treated rather poorly in modern stories, being presented as a too-big, beefy, well-meaning-but-clumsy type in deCamp/Pratt, and as a rigidly military fighting machine in Italo Calvino’s The Non-Existent Knight. I thought there ought to be more adventures for Bradamant as strong without being therefore laughable or unpleasant, and eventually decided to do something about that.

Oberon also makes an appearance in Bradamant’s Quest. I know he’s got roots in the Middle Ages, but has he played a role in Carolingian romances before? Would we recognize him from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (or would he recognize himself)?

Oberon the Fairy King is a major character in the 12th century Huon of Bordeaux, Huon being one of Charlemagne’s knights. The 1534 translation of it into English is where Shakespeare got his Oberon. The name is equivalent to Auberon, which is equivalent to the German Alberich, meaning elf-lord, although Oberon would not recognize himself in the Alberich of the stories of the Volsung Saga/Ring of the Nibelungs. Huon’s Oberon is enough like Shakespeare’s to make them recognizable, for instance, in their power and in their inclination to befriend mortals, although Shakespare made important changes, such as introducing Titania and Robin Goodfellow into Oberon’s court.

The romance authors of medieval Europe freely added to each other’s work, as when Ariosto wrote Orlando Furioso to finish Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato. These days, many people would call that plagiarism, or fanfiction (and which is more respectable?). What are your thoughts on this sort of collective fiction-making? Should we revise our ideas of originality and look at it differently today?

No one seems to object to modern Arthurian adventures. Jane Yolen likes to say that King-Arthur-and-his-knights make up one of the earliest shared-world settings, although by no means the earliest. Tennyson, when he was doing his retellings of stories from Greek mythology (and the same applies to his Arthurian adventures in his Idylls of the King) remarked in a letter to a friend that he did not like to re-tell a story if he thought it was simply a rechaufée, re-heated leftovers, but if he felt he had something to say that was more than could be found in the original, then he felt that his version was worth doing. And, as T.S. Eliot said: only bad poets borrow — good poets steal.

You’re a charter member of the Int’l Wizard of Oz Club, and you’ve been writing articles about fantasy literature and resurrecting lost stories for many years, as well as writing short stories. How does it feel to be publishing your first novel?

I’m delighted to have it in print. I remember some years back I was on a panel at a science-fiction convention about writing stories based on legends/myths. I tried to say something about Bradamant, and the moderator kept shutting me up, I think because she thought an unpublished novel could not be worth talking about. I take a good deal of satisfaction in thinking that now I can tell people about it, and if they think it sounds interesting, it’s possible for them to get it.

Gracious, I missed that Mari Ness at Tor was reviewing all the books by E. Nesbit!

I didn’t see a mention of how in her golden period Nesbit wrote for The Strand, so her books appeared first in that magazine in chunks and only later were collected. That helps to explain their episodic rhythm, especially in the early years.

Ness gets rather cutting on a time-travel novel that I haven’t been able to complete, Harding’s Luck:

Nesbit also choose[s] to make Dickie into a poor crippled orphan, and thus, Extremely Good, so Good that Dickie is willing to return to poverty and disability, giving up the pony, just to turn a homeless beggar and thief into a hardworking, honest man.That’s not a selling review, is it? The title of this illustration by H. R. Millar might sum up the tone that Ness disliked in the book: “It hurt, but Dickie liked it.”

I’m not certain that any writer could have pulled this off; certainly Nesbit couldn’t. I can believe in Nesbit’s magical rings and wishes; I can certainly believe in her portraits of children who do thoroughly selfish and foolish things or spend more time thinking about food and fun than about being good. But not this. . . .

By 1907/1908, when Nesbit was planning and writing Harding’s Luck, she was well established as a popular, clever, children’s writer. But then, as more than occasionally now, “popular,” “clever,” and “children’s” did not add up, in the eyes of important (and generally male) critics, as “good” or “of literary merit.” . . . Nesbit, on personal, friendly terms with some of these literary critics, knew what they were looking for, and she was prepared to change her writing to meet it. Thus the serious tone of this book, and its often self-conscious “literary” feel.

PERMANENT LINK:

10:39 AM

0

comments

![]()

Of all Lemony Snicket’s comments on the Occupy Wall Street movement and the financial/political elite’s reaction to it (also ensconced on Neil Gaiman’s website), I thought this was the most incisive:

Money is like a child—rarely unaccompanied. When it disappears, look to those who were supposed to be keeping an eye on it while you were at the grocery store. You might also look for someone who has a lot of extra children sitting around, with long, suspicious explanations for how they got there.When we start implicitly comparing mortgage barons to Count Olaf, they should know they’re in trouble.

Did you ever consider a sequel to David and the Phoenix?I think that reflects how the character of the Phoenix so dominated that book, and David was fairly blank. Any sequel would also have risked undercutting the first book’s theme of accepting the cycle of life and death. Ormondroyd did write a sequel to Time at the Top, once again featuring an author named Ormondroyd, and I may have to look that up now.

I not only considered it, I was fool enough to write it. Disaster! I threw away the whole book.

What was the sequel about? When did you write it? Did you save no copy?

Well, the Phoenix was irrevocably gone, so I substituted a gnome-like figure, and he and David set out on a quest, carried by a flying suitcase...but of course without the old Phoenix it was as useless as Gone with the Wind without Scarlett O'Hara. I can't remember when I committed this literary crime. No copy. My wastebasket is a receptacle of no return.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:58 AM

8

comments

![]()

Dorothy Gale lived on a farm in Kansas, with her Aunt Em and her Uncle Henry. It was not a big farm, nor a very good one, because sometimes the rain did not come when the crops needed it, and then everything withered and dried up. Once a cyclone had carried away Uncle Henry’s house, so that he was obliged to build another; and as he was a poor man he had to mortgage his farm to get the money to pay for the new house. Then his health became bad and he was too feeble to work. The doctor ordered him to take a sea voyage and he went to Australia and took Dorothy with him. That cost a lot of money, too.This was, of course, before American society decided that it was both heartless and wasteful to let medical costs force people into bankruptcy. Now, of course, we’ve progressed to... Never mind.

Uncle Henry grew poorer every year, and the crops raised on the farm only bought food for the family. Therefore the mortgage could not be paid. At last the banker who had loaned him the money said that if he did not pay on a certain day, his farm would be taken away from him.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:07 AM

2

comments

![]()

I think I speak for the entire paleontological community when I say: This is not what most of us do with our time, honestly.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:00 AM

4

comments

![]()

What’s more, one villain is monitoring events on TV screens while standing beside his exact scale-model of New York. The panels can thus shift from a real-life setting to a video image of that setting to a little replica of that setting. Yes, it’s more than occasionally confusing, but that mirrors the layering of the plot itself.

What’s more, one villain is monitoring events on TV screens while standing beside his exact scale-model of New York. The panels can thus shift from a real-life setting to a video image of that setting to a little replica of that setting. Yes, it’s more than occasionally confusing, but that mirrors the layering of the plot itself.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:36 AM

4

comments

![]()

For folks who weren’t in the room at the time, please tell the story of how you invented the Galaxy Games.Thanks, Greg! And now, today’s Galaxy Games puzzle piece.

The room in question was a breakout session at an SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) conference in Los Angeles. An editor was presenting a workshop on writing series for middle grade boys. She assigned us all genres in which to create a pitch, on the spot. Mine was sports. Since you were in the room, you heard me give a pitch for something I called “Galaxy Games” that was a lot like how the Galaxy Games series really did turn out.

For folks who were in the room but weren’t inside my head, I can go into even greater detail. Actually, I was disappointed at being given sports as a genre instead of fantasy or science fiction, which I thought of as my strengths. I follow sports, but I’d never read any sports series books, and I’d certainly never considered writing them. The first thing that came to mind was a manga called Slam Dunk, which follows a boys’ basketball team through a season of ups and downs. Another thing I had in mind was a baseball movie called The Bad News Bears, which was full of funny moments and dysfunctional players. The third thing was aliens, and lots of them. That’s where my high concept came from: The Bad News Bears in space, battling aliens in a season-long sports tournament.

How has Galaxy Games grown over the years since you first had the idea?

My original idea was to write a whole bunch of short chapter books. Now I have a smaller number of thicker and more complex books. The starting point has also changed. Originally, Earth was already in the tournament on Page 1 and we really didn’t know how. The Challengers tells that story and lets us see the first aliens arrive and the chain of wacky events that turn an ordinary Earth kid like Tyler Sato into a planetary team captain.

As a writing colleague, I've heard about a lot of your interests—the law, website design, real estate, schools, the Red Sox, wife and child—but until I read Galaxy Games: The Challengers I didn’t know about your experience with Japan. Tell us about that and how it fed into the book.

I studied in Tokyo during law school and have spent more time in Japan than in any other country outside the United States. I’m also a fan of manga and had an anime/manga style in mind while I was writing the series. When it came to fleshing out a team of kids from all over Earth, it was natural for me to put a special focus on Japan.

Are you choosing other Galaxy Games settings based on places you’ve traveled? Aruba? Ossmendia?

Since you’re read some early chapters from Book #2, you know that there will be a prominent character from Aruba for which I’m thankful to have spent some time in the Caribbean. I’m quickly running out of places I can write from actual experience, though, unless there’s a travel grant I can apply for. Ossmendia is like Europe in that I’ve only been there in my imagination.

Who or what are some of your influences as a storyteller? What storytellers did you find funny as a kid? What science fiction did you like most?

My mother is my greatest influence as a storyteller. She can take any incident and make it more dramatic and humorous at the same time. For science fiction influences, I’ll go with Isaac Asimov, Madeleine L’Engle, Piers Anthony, Frederic Brown, and Douglas Adams. For humor, I’ll single out Bugs Bunny.

Tyler Sato, the hero of Galaxy Games, gets a reputation as the best young athlete on the planet, but his skills are really average. And his choices for Earth’s true top young athletes seem questionable (though el Gatito would disagree). Were you aiming to write a sports book for kids who aren’t terribly good at any sports?

I could have made all the kids into superstars, but what fun would that be? My goal was that each member of the team would be chosen for exactly the wrong reason but would turn out to have some other quality, trait, or skill that would make them exactly the right player to be on the team at exactly the right time.

The Galaxy Games series takes the structure of a sports book: the training, the team dynamics, the higher and higher levels, the “big game” that decides everything. But a lot of the competitions are iffy. Adults keep trying to fix the games. The players all take advantage of loopholes in the rules. What does that tell our planet’s young athletes and sports fans?

That I’m a cynic? No, that’s not right. I think the key point is that sports is about more than just what happens on the field during game time. There’s training, practice, the locker room, the clubhouse, the team bus, the owner’s box, the bleachers, the bench, the talk radio shows, and everything else. This can’t just be a story about kids playing a game because too much planetary honor is on the line.

Which Galaxy Games Challenger do you identify with most?

Tyler Sato.

PERMANENT LINK:

7:32 AM

1 comments

![]()

When the book won a young-adult award from librarians, he was peeved. “I’d made something as mature as I was capable of making, and it seemed unfair that I was a victim of a prejudice against my medium,” he says. Ultimately, he says, “I reconciled to the fact that if ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ and ‘Huckleberry Finn’ can be considered children’s books, I can settle for ‘Maus’ being on those shelves.”Gulliver’s Travels is considered appropriate for young readers because of its fantastic element, and because many retellings have been bowdlerized of such scenes as Gulliver putting out a fire for the Lilliputians. Huckleberry Finn gets on that shelf because it has a child as protagonist and narrator. Maus is there because it’s in comics form, with talking animals.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:08 AM

0

comments

![]()

Two years ago, I took note of comments from bookseller Elizabeth Bluemle and librarian Betsy Bird about white adults who don’t want to take home books about children of color, but also don’t want to acknowledge that (perhaps even to themselves).

This month Bird offered another report at Fuse #8 about how some parents avoid the awkward words:

Parents these days speak in code. As a New York children’s librarian I had to learn this the hard way. Let’s say they want a folktale about a girl outwitting a witch. I pull out something like McKissack’s Precious and the Boo Hag and proudly hand it to them. When I do, the parent scrunches up their nose and I think to myself, “Uh-oh.” Then they say it. “Yeah, um . . . we were looking for something a little less . . . urban.”Of course, “urban” has a different value when paired with “fantasy,” and the result is marketed to adults and teens. What “urban fantasy” is may not be entirely clear (here’s one attempt at definition from RDW). But the scariness of the modern American city evidently has more literary value in supernatural thrillers.

Never mind that the book takes places in the country. In this day and age “urban” means “black,” so any time a parents wants to steer a child clear of a book they justify it with the U word, as if it’s the baleful city life they wish to avoid (this in the heart of Manhattan, I will point out).

PERMANENT LINK:

8:39 AM

0

comments

![]()

For each of the four Oz-book adaptations he’s scripted for Marvel Comics, Eric Shanower has drawn a variant cover for at least one issue.

For each of the four Oz-book adaptations he’s scripted for Marvel Comics, Eric Shanower has drawn a variant cover for at least one issue.

PERMANENT LINK:

9:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

PERMANENT LINK:

8:33 AM

2

comments

![]()

In 1988, I had come up with the basic storyline, but I was then suffering a terrible writer’s block, the only one in my career, thank God, although it lasted 5 years. George, then-editor Barbara Randall Kesel and I talked over what I’d come up with, and because of my block George went home and typed up the overview, breaking it down and filling it out with ideas, etc. We actually print that plot in the Games hardcover complete with annotations so people can see what had been and what was then changed. He then drew between 60-70 pages before going into a Titans block and stopped. I never dialoged any pages since I was waiting for them all to be finished so I could write them all at once. Also, I was hoping my block would go away as didn’t want to do less than my best on it.That delay also meant that Games has ended up standing outside the standard DC Comics continuity—which might well be a good thing.

But when we finally came back to the story 23 years later, since we had not really worked out the last 50 plus pages in any depth, and because neither of us could remember what we intended decades before, and the plot, frankly, would have felt dated, we decided to come up with a new story, utilizing and making sense of all the pages George had already drawn, yet written to have an entirely new meaning. I started re-plotting the story, adding in a new villains, plot twists and more, as well as suggesting we change the major villain who was actually behind the whole plot, which was new as well. We also had to come up with all new character-driven scenes to make what was supposed to have been a pure action story into something much more. (As a companion piece to the regular book we were working on, a solid action book would have worked. Twenty-three years later that would not have been satisfying to any of us who had been waiting so long.)

Knowing the new character scenes which George and I worked on together, batting ideas back and forth as we always had, I then was able to dialog the earlier, already drawn pages, in a way that would cleanly set up where we were going to go. When you read it you will assume that was what was intended all along, because the copy and art work perfectly together, but it’s new. George and I would go back and forth and I’d rewrite the ideas and we finally had a story that was much, much stronger than had originally been designed.

At Salon, Paul LaFarge discusses the fate of hypertext fiction, celebrated as the coming new thing in the 1990s and forgotten today.

At Salon, Paul LaFarge discusses the fate of hypertext fiction, celebrated as the coming new thing in the 1990s and forgotten today.

Born into a world that wasn’t quite ready for it, and encumbered with lousy technology and user-hostile interface design, it got a bad reputation, at least outside of specialized reading circles. At the same time, it’s impossibly hard to create, one of the only modes of fiction I know of which is more demanding than the novel. (And then add to that the need to create a user interface, and maybe a content-management system, and is it going to be an app? Suddenly your antidepressants aren’t nearly strong enough to get you out of bed.)LaFarge name-checks several print precursors to digital hypertexts: Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-69), Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962), Júlio Cortázar’s Hopscotch (1963), and Jacques Roubaud’s The Great Fire of London (1989).

It’s tempting to leave the story there, and to let the hypernovel, or whatever you want to call it, become part of the technological imagination of the past, like the flying car. But I believe that the promise of hypertext fiction is worth pursuing, even now, or maybe especially now. On the one hand, e-books are beginning to offer writers technical possibilities that, being human, we’re going to be unable to resist. On the other, the form fits with life now. So much of what we do is hyperlinked and mediated by screens that it feels important to find a way to reflect on that condition, and fiction, literature, has long afforded us the possibility of reflection.

Just as the novel taught us how to be individuals, 300 years ago, by giving us a space in which to be alone, but not too alone — a space in which to be alone with a book — so hypertext fiction may let us try on new, non-linear identities, without dissolving us entirely into the web.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

…books don’t want to be free; they just want to be a whole lot cheaper than they are. And when you make books (not all books, but some) $4.99 or $1.99 or even 99 cents, people will buy more of them. . . .I doubt that people would sign up for anything an author writes. But they might well sign up for notifications (and one-click purchasing) of anything she writes, so they can be sure of the genre, main character, or other necessary qualities. If such a system takes place, it will surely change the nature of the writing, just as we can tell where Dickens broke off his serialized installments while making sure readers would come back for the next.

There’s even the possibility that books could be free and still make money: Amazon has an ad-supported Kindle, so why not extend that model to the books themselves? Magazine writers publish their content in an ad-supported medium, so why not books? Authors such as Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle wrote many of their novels on a monthly basis as magazine supplements. And Amazon apparently already has a patent that covers advertising-supported e-books.

As we’ve pointed out before, the book is evolving as it becomes digital — there are Kindle Singles that aren’t much longer than a magazine-length feature, and some magazines and newspapers are packaging features in just that format, as well as newer services like Byliner that have been commissioning custom content. A free Kindle could be just the beginning of an explosion of book-like content from Amazon and others: The company is already talking about a “Netflix for books” that would offer content for a monthly fee.

Why not offer a subscription to an author, so I can automatically get whatever he or she writes, regardless of length or format? This would blend the worlds of blogging, Kindle Singles, magazine-length features and novels into one stream of content, and I’d be willing to bet more people would read more as a result. The printed book, as Seth Godin wrote recently, is a fetish of sorts, like an expensive watch: something we buy because we like to look at it, but something that is no longer really functional or necessary. In the end, that’s likely to be a good thing, not a bad one.

PERMANENT LINK:

10:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

From the opening chapter of L. Frank Baum’s Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz:

The little girl stood still to watch until the train had disappeared around a curve; then she turned to see where she was.Image from the opening pages of the Marvel Comics adaptation of Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, drawn by Skottie Young from a script by Eric Shanower.

The shed at Hugson’s Siding was bare save for an old wooden bench, and did not look very inviting. As she peered through the soft gray light not a house of any sort was visible near the station, nor was any person in sight; but after a while the child discovered a horse and buggy standing near a group of trees a short distance away. She walked toward it and found the horse tied to a tree and standing motionless, with its head hanging down almost to the ground. It was a big horse, tall and bony, with long legs and large knees and feet. She could count his ribs easily where they showed through the skin of his body, and his head was long and seemed altogether too big for him, as if it did not fit. His tail was short and scraggly, and his harness had been broken in many places and fastened together again with cords and bits of wire. The buggy seemed almost new, for it had a shiny top and side curtains. Getting around in front, so that she could look inside, the girl saw a boy curled up on the seat, fast asleep.

She set down the bird-cage and poked the boy with her parasol.

With ink inscription on front free endpaper, “Richard Adlai Watson, from his Godfather R.J. Street, May 23, 1900”; [bibliographers] Bienvenue & Schmidt note that “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz had its official publication on September 1, 1900,” making this a very early pre-publication copy. In fact, it pre-dates the copy given by [L. Frank] Baum to his brother, which he noted in the May 28, 1900 presentation inscription as “the first copy of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz that left the hands of the publisher.” The present copy was known to Justin Schiller, and in 1970 he speculated that Street was somehow involved in the publication of the book, and took a fresh copy from the press before Baum had a chance to get one.This thing called the internet allows us to learn more about the people involved in this gift.

PERMANENT LINK:

8:39 AM

4

comments

![]()

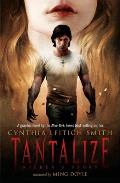

Today artist Ming Doyle signs copies of Tantalize: Kieren’s Story, a graphic retelling of the events in Cynthia Leitich Smith’s novel Tantalize, at the Brookline Booksmith.

Today artist Ming Doyle signs copies of Tantalize: Kieren’s Story, a graphic retelling of the events in Cynthia Leitich Smith’s novel Tantalize, at the Brookline Booksmith.

In honor of that event, this weekly Robin quotes from Smith and Doyle’s Newsarama interview:

Nrama: What characters in comics would you like to write/draw a story with?Smith has also expressed her admiration for Wonder Woman. Of course, that was before the DC Universe’s latest retelling.

Smith: I’ve always been fond of Tim Drake/Robin. I suppose it’s the YA writer in me. I enjoy the intensity of young, smart heroes. I’d love to write him in either graphic or prose form.

Doyle: Tim Drake’s actually a character I have a lot of interest in as well! In general, I’ve always been drawn to the Bat family and its associates.

PERMANENT LINK:

6:45 AM

0

comments

![]()

Published first in 1958, The Rabbits’ Wedding features black and white rabbit protagonists. The artist most likely chose these colors to help delineate the two characters in a limited-color book, but adults interpreted this lovely romp in the forest as an endorsement of interracial marriage.Showing how much things have changed, the most frequently challenged book in America last year was And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, a picture book about two male penguins who raise a chick together. Adults interpret that true story as an endorsement of same-sex marriage.

As Leonard Marcus recounts the controversy in Minders of Make-Believe, the Montgomery Home News condemned the book, then Alabama politicians rallied against the book and spoke out against the director of the Alabama Public Library Service Division, Emily Reed.

J. L. BELL is a writer and reader of fantasy literature for children. His favorite authors include L. Frank Baum, Diana Wynne Jones, and Susan Cooper. He is an Assistant Regional Advisor in the Society of Children's Book Writers & Illustrators, and was the editor of Oziana, creative magazine of the International Wizard of Oz Club, from 2004 to 2010.

Living in Massachusetts, Bell also writes about the American Revolution at Boston 1775.