Male and Female Storytelling Energies?

Last week, in a discussion on Facebook of whether Harry Potter is a feminist saga (prompted by this essay), author Bruce Coville shared some interesting thoughts about what defines a “boy book”:

I think gender roles are one of the areas in which Rowling’s execution actually undercuts the values on the surface of her books. But Coville is correct about the types of energy she’s combined in her story, whether or not those are intrinsically male and female.

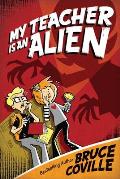

It's not the gender, it's the energy. I've spent a couple of decades thinking about this, in no small part because of the reaction to MY TEACHER IS AN ALIEN. This is a book I wrote first person female, yet it is still considered a "boy's book." I cracked my brain over this for a long time, and in the end I came to the conclusion that it's about the "storytelling energy" of a story. . . .Coville has been talking about that blend for years, which is why I feel comfortable quoting his Facebook comments.

The very best (and most successful) books partake equallly of male storytelling energy (action!) and female storytelling energy (relationship).

Jo Rowling merges them seamlessly.

I think gender roles are one of the areas in which Rowling’s execution actually undercuts the values on the surface of her books. But Coville is correct about the types of energy she’s combined in her story, whether or not those are intrinsically male and female.

3 comments:

You're seeing much more interesting discussions on Facebook than I am.

I would agree with those people who feel the women in the Harry Potter books primarily fill sex-role stereotypes--teachers and mothers. Mrs. Weasley...the stereotypical earth mother of a big brood but with magic she can use to protect her young. Lily...the classic mother who dies for her child. And dying for your child is highly regarded in these books because it's her sacrifice that makes Harry's magic so powerful. Hermione is your classic/stereotypical annoying smart girl. I realize that none of the teachers at Hogwarts are married, but that still means the women teachers are filling the old maid teacher stereotype.

I believe there was one young, edgy, nonfeminine magical woman in the series, and if memory serves me she got what usually comes to women in literature who don't stay in their place.

I guess I’m not surprised that most of the women in a series of school stories are mothers (or mother-figures) and teachers. Most of the men are father figures and/or teachers, after all.

Among the girls, Rowling clearly chose to make no gender distinctions within Hogwarts. There’s no girls’ quidditch team. Still, as I’ve noted before, the girls tend to be attacked through their looks (Hermione’s teeth, Katie’s opal necklace) rather than physically like the boys. I can think of four boys we meet as Hogwarts students who are killed by the end, but no girls.

With such a large cast, I think there’s actually quite a range of female types. Beyond Hermione, mothers, and teachers, there are other students (Cho, Luna, Ginny, Fleur, etc.) and villains (Rita Skeeter, Umbridge, Bellatrix, etc.). I don’t sense full gender parity, but the females aren’t just tokens.

I understand that Rowling didn’t originally mean to kill off her “young, edgy nonfeminine magical woman” among the heroes’ adult supporters, along with her husband. She’s said that she decided to do so after revising plans to kill another character—Mr. Weasley—earlier in the series. That did end up removing two of the sympathetic rule-breaking characters from the restored order—another example of the unconscious undercutting of the series’ surface values.

I think how readers respond to these characters will probably be determined by how much they like the books. If you like the books, the characters are classics, archetypes; if you don't, they're stereotypes.

For instance, I found Rita Skeeter to be a cartoon manipulative, grasping woman reporter and Bellatrix very Dragon Ladyish/Cruella de Ville. Of course, I don't know if that necessarily makes them sex role stereotypes, just stereotypes.

I have trouble keeping the nonHermione girls apart, which, again, doesn't necessarily make them sex role stereotypes.

Post a Comment