Weekly Robin Robinson Edition

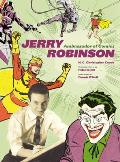

This spring the National Cartoonists Society was in town, and Jerry Robinson, principal creator of Robin, did a signing at Comicopia. I got his autograph in a copy of Batman: From the ’30s to the ’70s, the book where I first saw his art (uncredited, of course), and in N. Christopher Crouch’s illustrated biography, Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of Comics.

I’ve written about how at Oz conventions I ask men who played Munchkins in the MGM Wizard of Oz about their experience of World War II. The surviving performers were in their teens or early twenties back in 1938 during filming, and thus of military age during the war. But their height made them ineligible for military service. That question has prompted stories of piloting planes for the Civil Air Patrol, putting one’s small size to work repairing planes, and working on a farm.

I knew that when Jerry Robinson met Bob Kane in 1939, he was about to start college, meaning he was the same age as those former Munchkins. So I asked Robinson about his wartime experience. He shared an anecdote that isn’t in the book, so I’m setting it down in pixels for posterity’s sake.

Robinson was in Florida when he received an invitation from his draft board back in New York City to report for a physical. Not the sort of invitation a man could ignore. And since he’d already had two exams and been rejected for low weight and poor vision, Robinson figured things might be looking desperate for the Allies.

He found a plane headed back to New York. During the war, he said, it was tough to find regular flights, but a lot of small operators jumped in to fill the gaps—guys who might own one airplane.

He found a plane headed back to New York. During the war, he said, it was tough to find regular flights, but a lot of small operators jumped in to fill the gaps—guys who might own one airplane.

Without other options, Robinson got on a plane with seats for six passengers. But his seat wasn’t in the cabin. The pilot asked him to sit in the co-pilot’s seat and hold the maps, looking out the window for landmarks to keep the flight on course.

After several hours Robinson landed, having had a rare perspective on America’s East Coast. He reported to his draft board for his third physical—only to be rejected for bad vision.

Of course, Robinson was then making his living as a visual artist, and had just managed to navigate from Florida to New York by sight. But the ocular requirements for a rifleman must have been tougher.

The doctor told Robinson (and this punch line is in the book), “Look, son, we’ll call you when the Nazis get to Fourteenth Street.”

I’ve written about how at Oz conventions I ask men who played Munchkins in the MGM Wizard of Oz about their experience of World War II. The surviving performers were in their teens or early twenties back in 1938 during filming, and thus of military age during the war. But their height made them ineligible for military service. That question has prompted stories of piloting planes for the Civil Air Patrol, putting one’s small size to work repairing planes, and working on a farm.

I knew that when Jerry Robinson met Bob Kane in 1939, he was about to start college, meaning he was the same age as those former Munchkins. So I asked Robinson about his wartime experience. He shared an anecdote that isn’t in the book, so I’m setting it down in pixels for posterity’s sake.

Robinson was in Florida when he received an invitation from his draft board back in New York City to report for a physical. Not the sort of invitation a man could ignore. And since he’d already had two exams and been rejected for low weight and poor vision, Robinson figured things might be looking desperate for the Allies.

He found a plane headed back to New York. During the war, he said, it was tough to find regular flights, but a lot of small operators jumped in to fill the gaps—guys who might own one airplane.

He found a plane headed back to New York. During the war, he said, it was tough to find regular flights, but a lot of small operators jumped in to fill the gaps—guys who might own one airplane. Without other options, Robinson got on a plane with seats for six passengers. But his seat wasn’t in the cabin. The pilot asked him to sit in the co-pilot’s seat and hold the maps, looking out the window for landmarks to keep the flight on course.

After several hours Robinson landed, having had a rare perspective on America’s East Coast. He reported to his draft board for his third physical—only to be rejected for bad vision.

Of course, Robinson was then making his living as a visual artist, and had just managed to navigate from Florida to New York by sight. But the ocular requirements for a rifleman must have been tougher.

The doctor told Robinson (and this punch line is in the book), “Look, son, we’ll call you when the Nazis get to Fourteenth Street.”

No comments:

Post a Comment