This past week turned out to be significant in Robin history. Robin, #174, confirmed what DC Comics magazines and editors had been hinting for months: that Stephanie Brown, the (by my count) fifth teenager to take the role of Robin, wasn't dead after all.

This past week turned out to be significant in Robin history. Robin, #174, confirmed what DC Comics magazines and editors had been hinting for months: that Stephanie Brown, the (by my count) fifth teenager to take the role of Robin, wasn't dead after all.

A little background. In 1992, shortly after Tim Drake debuted as the fourth Robin, the Batman comics introduced Spoiler: a female acrobatic masked vigilante in eggplant-colored tights and cape. Tim tracked down the Spoiler and identified her as Stephanie Brown, the teen-aged daughter of a minor villain named the Cluemaster. She was trying to fight crime--on a shoestring budget, with no mentor--out of embarrassment about her father.

The following year, DC launched the ongoing Robin comic book, and Tim's relationship with the slightly older Stephanie was a major plot engine over the next decade. As Chuck Dixon, the magazine's writer until 2002, said in a recent interview:

Frankly, Spoiler began as a pure plot device and evolved, because of fan interest, into a romantic foil for Robin. . . . It's also kind of cool that Robin has someone around his own age to run rooftops with. It's sort of a male fantasy to find a girl who shares your hobby.

Tim and Stephanie fell in love, had a baby (not his, but he helped at the birth), broke up, got back together, and went through other experiences of hormonal teenagers. On top of that, they had the typical experiences of comic-book heroes: finding out secret identities, switching bodies, having to fight their own parents, dealing with jealous ghosts, and so on.

In 2004, DC hired

Bill Willingham to script the

Robin series. I've mentioned Willingham's

Fables comics favorably, and will have more to say about them in due course.

Comic Book Resources interviewed Willingham about his eventful stretch of

Robin comics:

CBR: While writing "Robin," the character has gone through some major changes, including his father finding out about his secret identity, the death of his father, the death of his girlfriend, and relocating to a new city. How many of these changes originated with you, and how many were given to you to explore by editors?

BW: What a nice way to put that - "...given to you to explore by editors" as opposed to, "inflicted on you against your will and better judgment," Well done. Very diplomatic. . . .

CBR: Despite all the changes the character has gone through, all of Robin's actions seemed true to his character.

BW: How nice of you to say, but some readers might disagree with that.

And so, it's apparent, might Willingham. The story of Tim Drake's father learning that he's been spending his nights as Robin, instead of, oh, playing in a midnight basketball league, appears in the collection

Robin: Unmasked.

Tim's resignation for his dad's sake left Batman without a teen-aged partner. Meanwhile, the Batman editorial team had plans for a big "crossover" story to promote all their magazines, which would need some striking landmark event to drive the plot. These days, such comic-book events usually involve a character dying. Willingham had a bright idea, as he explained in that interview:

The death of Spoiler was locked in before I was asked to take over the series, but it was my idea to let her become Robin for a short time before that. My thinking is that it would be nice to give her at least one moment of glory, accomplishment and success, before all of those horrible things that were destined to happen to her.

Thus, Stephanie Brown became the first female Robin within the regular DC continuity. Most of the Batman stories in which she wears the red and green costume appear in a collection called

Batman: War Drums. According to Willingham in an interview with Word Balloon

quoted at evenrobins.net:

There was a nice spike in sales during that time and I wish her death hadn’t been so as locked in because when it started going really well, what I would have liked to have said was, "Let’s follow this for a while." That was not available as an option and you can’t really...do that same stunt over and over again. We had that momentum once, we lost it.

The long-planned crossover is archived in the three

Batman: War Games volumes; many fans seem to feel that's three too many. Having been fired as Robin, Stephanie returns to her Spoiler role and ignites a gang war. A villain named Black Mask captures and tortures her. Tim Drake returns as Robin, sadder and madder. Batman beats up people. And, we are given to understand, Stephanie Brown dies for our entertainment.

Here's a passage from yet another interview with Willingham, from the

AV Club, on his great notion:

My personal theory is that we've all got this bucket full of good ideas, and if you just hold onto them, your bucket never gets fuller. There's only so many you can hold at a time, but as fast as you use them up, it fills up again with more good ideas. My notion is to spend everything you've got coming through your head as fast as you can, and you're guaranteed to get more good stuff.

So while writing Robin and stuff like that, if I had good ideas, I'd try to pitch them and run with them. Sometimes it backfired. It was my idea to make Spoiler into Robin, just before she died horribly. I thought that would be a good thing for the character, but it turns out that legions of female fans now detest me for doing that.

Indeed, they did. Which seems unfair because DC's (outgoing) editorial powers had decided on the death of Stephanie Brown before Willingham took the job.

Critics saw Stephanie's violent death as fitting into a larger pattern of how comic books exploit supporting female characters to provide angst for leading male characters. Ten years ago the website

Women in Refrigerators catalogued many other examples of female characters and their suffering. This list is not unlike the one about

gay superheroes killed in mainstream comics that novelist

Perry Moore assembled. I'd like to see a comparative analysis of straight male secondary characters and their fates as well; those guys may also be plot fodder.

Since DC killed and resurrected

Superman in the early 1990s, death and rebirth have been superhero clichés. When a company could thrive while (temporarily) killing off even its oldest, strongest, and most lucrative trademark, a supporting character like Spoiler doesn't stand a chance of avoiding the grim reaper. But any comic-book death, unless it defines a hero's origin (as in the killing of Bruce Wayne or Dick Grayson's parents,

Peter Parker's uncle, or the entire planet of Krypton), can be reversed when the market seems right.

Gail Simone, the creator of Women in Refrigerators, had a simpler argument for the superhero comics publishers: How will you attract female readers and stay in business if you keep killing off or hurting your female characters? Her criticism brought her to the attention of DC Comics, which hired her to script

Birds of Prey, about an all-female superhero team (which had at times included Spoiler as a trainee), and now

Wonder Woman.

The elimination of Stephanie Brown inspired more specific protest, such as this

open letter from Katherine Keller and other internet essays. Fan anger focused around

Project Girl Wonder, an email crusade to have the Batcave include a memorial for Stephanie, just as there was one for the

third Robin, Jason Todd. (He's come back from the dead, too, a couple of years ago.)

As the clues piled up this spring that Stephanie would be brought back alive, the Girl-Wonder.org website suspended its campaign. Project Girl Wonder had probably played a role in the character's return--not by putting pressure on DC Comics in a political sense, but by showing that Spoiler had her own fervent fan base. [

Girl-Wonder.org remains active as a source of commentary on the bigger, ongoing issue of females in superhero comics.]

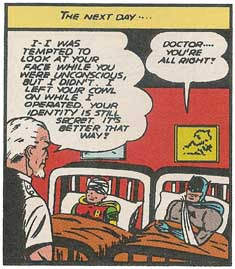

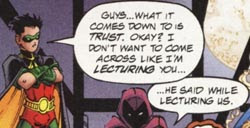

Now Stephanie's back. And as you can see in this image from the latest

Robin, drawn by Chris Batista and Cam Smith, Tim's very pleased to see her. (Yes, he does have a

bo staff on his belt, but he really is pleased to see her.) One question now is whether Stephanie Brown was popular

because she was unfairly treated and cruelly killed off, or because of some internal appeal of her personality that can keep her around.

Next month brings a one-off

Robin/Spoiler magazine. The

cover by Rafael Albuquerque (at top) pays tribute to Carmine Infantino's iconic image from the late 1960s of Batman and Robin on a rooftop. Visit the ad-heavy

Bat-Blog to see the original and some previous homages.

The Atlantic's June issue also contains an alarming story by Gregg Easterbrook on the threat of large asteroids and comets striking Earth in ways that could end human civilization or even the human species.

The Atlantic's June issue also contains an alarming story by Gregg Easterbrook on the threat of large asteroids and comets striking Earth in ways that could end human civilization or even the human species.

The elimination of Stephanie Brown inspired more specific protest, such as this

The elimination of Stephanie Brown inspired more specific protest, such as this

Last November,

Last November,

Some Oz and Readers might have assumed (or hoped) that PUNCTUATION WEEK would mean skipping a

Some Oz and Readers might have assumed (or hoped) that PUNCTUATION WEEK would mean skipping a  The panel on the right shows a rather unusual use of punctuation in a superhero comic dating from the "Golden Age" or early "Silver Age." Indeed, that usage probably shows up in this panel only because it was created in 1943, when the standard style was still being developed. Can you spot the detail?

The panel on the right shows a rather unusual use of punctuation in a superhero comic dating from the "Golden Age" or early "Silver Age." Indeed, that usage probably shows up in this panel only because it was created in 1943, when the standard style was still being developed. Can you spot the detail? Instead, most remarks in speech balloons became exclamations! Everything was dramatic! Even the most mundane remarks!

Instead, most remarks in speech balloons became exclamations! Everything was dramatic! Even the most mundane remarks! And what about those two hyphens? It's almost impossible to find an

And what about those two hyphens? It's almost impossible to find an  On the left,

On the left,  Nevertheless, neither the interrobang nor the juxtaposition of question mark and exclamation point fits in standard prose. They belong only in the most informal or experimental writing. To include them in a book manuscript is to risk being perceived as someone who hasn't read enough books to pick up the rules.

Nevertheless, neither the interrobang nor the juxtaposition of question mark and exclamation point fits in standard prose. They belong only in the most informal or experimental writing. To include them in a book manuscript is to risk being perceived as someone who hasn't read enough books to pick up the rules.