This is not yet another weekly Robin essay about the costume of Robin the Boy Wonder. No, these are remarks on the costume that Dick Grayson, the original Robin, adopted after he gave up that crime-fighting moniker.

This is not yet another weekly Robin essay about the costume of Robin the Boy Wonder. No, these are remarks on the costume that Dick Grayson, the original Robin, adopted after he gave up that crime-fighting moniker.

In 1984, Dick was a central character in DC's most popular comic book, The New Teen Titans. But he was also still an occasional supporting character in various Batman comics, meaning that the New Teen Titans creative team, Marv Wolfman and George Pérez, had to consult with the Batman squad on any major events involving him. "A trip into space to visit his gorgeous alien girlfriend's parents and, incidentally, save the planet? Sorry, not this month--he has to be in Gotham to stumble onto a payroll robbery and get tied up by crooks."

Eventually the company decided to have the Batman team create a new Robin (the first Jason Todd), while Wolfman and Pérez got to portray Dick adopting a new persona: Nightwing! That name, and the mostly dark blue costume he started wearing, were tributes to Batman (and, for those in the know, Superman), but the new identity was also a signal that Dick Grayson had come of age. After over forty years, he'd left the protection and shadow of Batman's cape. He didn't even need a cape of his own.

Some fans today find the original Nightwing costume quaint. Criticism centers on the "disco collar," but I'm sure practical people also find fault with the neckline that leaves so much chest exposed, and how the light blue and yellow would stand out at night. (Since most Titans missions took place in the daytime, that wasn't a problem.)

Since I was a New Teen Titans fan before I stopped reading comics altogether for quite a while, this Nightwing costume looks just fine to me. After all, a handsome man looks good in anything he wears.

Except a mullet.

Except a mullet.

At some point in the early 1990s, for reasons I don't understand and the World Wide Web wasn't around to record in detail, Dick started wearing a new Nightwing costume. It had more bright yellow areas, and something resembling feathers folded between the arms and the chest.

Dick also grew his hair long in the back. At times he wore it in a ponytail, such as when he had to fit it inside the Batman cowl during a brief period of standing in for Bruce Wayne. Around 1995, in the Nightwing: Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick's hair reached full Fabio proportions, as shown to the right.

Dick also grew his hair long in the back. At times he wore it in a ponytail, such as when he had to fit it inside the Batman cowl during a brief period of standing in for Bruce Wayne. Around 1995, in the Nightwing: Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick's hair reached full Fabio proportions, as shown to the right.

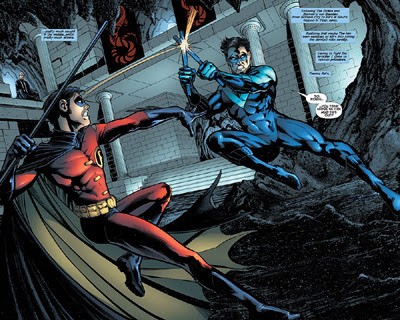

This costume also allowed Nightwing to glide through the air in a prone position. Apparently all that we humans need to become aerodynamic is to wear some yellow fans in our armpits. The panel below shows Dick traveling that way while Tim Drake, the fourth Robin, swings on a rope in more traditional fashion. (They may appear to be making catty remarks about their acquaintance Jean Paul's taste in capes, but it's a passionate discussion about the previous stand-in for Bruce Wayne.)

During the Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick Grayson received yet another Nightwing costume, but this one looked really good. No yellow anymore--just black highlighted with a jagged blue stripe from the fingers of one hand to the fingers of the other. And in the first issue of Nightwing magazine in 1996, some bad guys sliced off Dick's ratty ponytail, thank goodness.

During the Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick Grayson received yet another Nightwing costume, but this one looked really good. No yellow anymore--just black highlighted with a jagged blue stripe from the fingers of one hand to the fingers of the other. And in the first issue of Nightwing magazine in 1996, some bad guys sliced off Dick's ratty ponytail, thank goodness.

Since then, the Nightwing look has remained generally consistent, as shown in the big picture below. Dick's hair has sometimes been long and messy, but never again in a style made famous by hockey players. The simplicity of the costume lets artists put their attention to the acrobatic body it sticks to.

Since then, the Nightwing look has remained generally consistent, as shown in the big picture below. Dick's hair has sometimes been long and messy, but never again in a style made famous by hockey players. The simplicity of the costume lets artists put their attention to the acrobatic body it sticks to.

Nightwing doesn't need to fly, as the cover image to the left shows. Through his extraordinary athletic ability and readers' willingness to suspend disbelief, Dick can jump off buildings and catch himself on the way down. This picture also shows the eskrima sticks that Nightwing adopted as his signature non-lethal weapon at some point.

For a brief period in 2005 Nightwing started to wear a red and maroon variation on his regular outfit, as shown on the Renegade collection. That costume lasted about five issues, which I haven't seen. Most comics fans seem to think that storyline better forgotten.

For a brief period in 2005 Nightwing started to wear a red and maroon variation on his regular outfit, as shown on the Renegade collection. That costume lasted about five issues, which I haven't seen. Most comics fans seem to think that storyline better forgotten.

The image below, created by Ryan Sook, appeared on a 2007 issue of Nightwing magazine and then on the Lost Year graphic novel, issued last month. It shows Dick Grayson in his current costume with two of his previous outfits reflected in the windows around him. It's a very handsome portrait, but I still wonder why we don't see the real Nightwing costume with the spiffy collar.

Here are a few provocative remarks from this week's "Think Future" panel on what distinguishes Young Adult literature from adult literature, as reported by panel host Publishers Weekly. The panelists addressed the never-ending question of what distinguishes "young adult" literature. Perhaps because of demographics, we seem to have shifted from how YA differs from books for "tweens" and younger to how YA differs from adult books. And by "provocative," I hope to mean "thought-provoking" as well as "attention-getting."

Here are a few provocative remarks from this week's "Think Future" panel on what distinguishes Young Adult literature from adult literature, as reported by panel host Publishers Weekly. The panelists addressed the never-ending question of what distinguishes "young adult" literature. Perhaps because of demographics, we seem to have shifted from how YA differs from books for "tweens" and younger to how YA differs from adult books. And by "provocative," I hope to mean "thought-provoking" as well as "attention-getting."

This is not yet another

This is not yet another

Except a mullet.

Except a mullet. Dick also grew his hair long in the back. At times he wore it in a ponytail, such as when he had to fit it inside the Batman cowl during a brief period of standing in for Bruce Wayne. Around 1995, in the Nightwing: Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick's hair reached full Fabio proportions, as shown to the right.

Dick also grew his hair long in the back. At times he wore it in a ponytail, such as when he had to fit it inside the Batman cowl during a brief period of standing in for Bruce Wayne. Around 1995, in the Nightwing: Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick's hair reached full Fabio proportions, as shown to the right. During the Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick Grayson received yet another Nightwing costume, but this one looked really good. No yellow anymore--just black highlighted with a jagged blue stripe from the fingers of one hand to the fingers of the other. And in the first issue of Nightwing magazine in 1996, some bad guys sliced off Dick's ratty ponytail, thank goodness.

During the Ties That Bind miniseries, Dick Grayson received yet another Nightwing costume, but this one looked really good. No yellow anymore--just black highlighted with a jagged blue stripe from the fingers of one hand to the fingers of the other. And in the first issue of Nightwing magazine in 1996, some bad guys sliced off Dick's ratty ponytail, thank goodness.