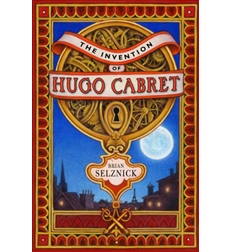

A Real Graphic Novel: Hugo Cabret

The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznick, is a graphic novel. Unfortunately, in a bid for literary respectability a couple of decades ago, comics genius Will Eisner coined the term "graphic novel" for what was in fact a collection of his comics. Thus, when we now hear "graphic novel," we think "comics over 48 pages long that take themselves seriously."

The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznick, is a graphic novel. Unfortunately, in a bid for literary respectability a couple of decades ago, comics genius Will Eisner coined the term "graphic novel" for what was in fact a collection of his comics. Thus, when we now hear "graphic novel," we think "comics over 48 pages long that take themselves seriously."

But Hugo Cabret actually has the length, plot, and undeniable weight of a novel. Its graphic elements are a crucial part of the storytelling, both in content and theme. It's therefore a graphic novel. But it's not comics.

The pictures in Hugo Cabret don't work like the pictures in comics. They're sequential, to be sure, but only one image is visible on each page spread. We move from one to the next through by turning pages, so we can never take in two images at once.

Furthermore, those pictures don't combine words and images the way most comics do. In fact, the pictures are almost empty of words. One shows a sign over an old man's toy stand which says, "JOUETS"; most American readers won't be able to read that. Another picture shows an automaton signing the old man's name. In all the rest, including scenes in the train station and in a bookstore, there are no signs or titles to read. On page 143 Hugo reads a note, but we readers never see an image of that note, even one created typographically.

Hugo Cabret actually tells us what storytelling model it's based on. On page ix the yet-unnamed narrator asks us to imagine that we're in a cinema, with the curtain opening on a screen. To reinforce that point, the book contains several stills from movies, such as Safety Last and A Trip to the Moon.

After the young characters sneak into René Clair's The Million, the text tells us that Hugo “thought every good story should end with a big, exciting chase.” And sure enough, two hundred pages later there's a big chase through the tunnels of the railroad station with the background blurring to convey the speed. (This is a technique from Japanese comics as well as cinema.) At the end of that chase Hugo gets caught and locked up, but no matter; on page 458 he escapes again, so that pursuit seems to be in the book just for the excitement.

Selznick's pictures work like movie shots, not like comics panels or picture-book spreads. Sequences of drawings narrow in on details, track moving characters, cut and dissolve from one image to another.

Furthermore, we're really supposed to look at each image only once before moving on to the next. The pictures don't reward close examination or reexamination. In a scene of Hugo making his way across the crowded train station, for example, his face is the only one that's clearly rendered, focusing our attention on him just as good Hollywood lighting and cinematography would. There are no important details to collect after your first impression. These images are like frames of a film, each a burst of visual information rather than a landscape to visit at your leisure.

TOMORROW: So what does that all add up to?

No comments:

Post a Comment