The Back of The Man in the Ceiling

NON-COMICS WEEK at Oz and Ends continues with thoughts on novels about creating comics--more specifically, creating adventure comics of the sort that dominate the field in America.

NON-COMICS WEEK at Oz and Ends continues with thoughts on novels about creating comics--more specifically, creating adventure comics of the sort that dominate the field in America.

As comics have achieved more literary respect, so respectable fiction has opened up to stories about the crafting those comics. The leading example in literary fiction is Michael Chabon's The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001, the year after it was published. Can you imagine an American novel published in the 1950s through the 1980s that treated the creation of a superhero comic called The Escapist as a serious enterprise? Showing an author or artist toiling in that field would more likely have signaled creative frustration or a fall.

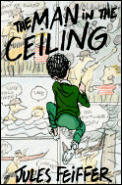

I think the real start of this trend was Jules Feiffer's The Man in the Ceiling, published for young readers in 1993 and put on some of that year's "best" lists. It's about a boy named Jimmy trying to create comics for popularity and self-respect, against a backdrop of his uncle's efforts to write a Broadway musical and ordinary family life.

Feiffer had already written about the comics he drew as a boy in The Great Comic Book Heroes. I think there's a fair amount of autobiography in this first novel. As I wrote earlier, The Man in the Ceiling doesn't have the period detail to set it in the 1930s and ’40s, when Feiffer grew up, but neither does it quite feel like it's taking place in the 1990s. One of the giveaways is the type of comic book Jimmy creates; his stories seem to reflect the anything-goes period when superheroes were still new rather than the continuity-, celebrity-, and event-driven business of the last two decades.

In addition to treating comics as a respectable hobby for a young fellow, The Man in the Ceiling also took a step forward in integrating text and illustration in a middle-grade novel. Now we see a lot more of that: Ruth McNally Barshaw's Ellie McDoodle, Jeff Kinney's Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and Greg Fishbone's Penguins of Doom are all very recent examples.

How tightly are words and pictures integrated in The Man in the Ceiling? Here are the novel's last words:

Jimmy dug his head deep into Uncle Lester's shoulder, forcing him to bring his right arm up to get a better hold. His right hand grasped a sheet of paper that Mother had not noticed before. Uncle Lester gripped it tight, as if it meant the world to him. Mother tried to see what was on it, but couldn't, so she moved quietly and swiftly down the steps to get a better look.You then turn the page and see--well, I'm not going to spoil it. But I will say that this ending doesn't translate well to an audiobook. I had to go back to the library for a print edition in order to understand what was going on.

See for yourself, it's the last page of this book.

2 comments:

I can't imagine this as an audiobook. I didn't much care for it, but it was interesting in how the graphics were integrated. I've not seen anyone else who has read this or who has it in their school library. (I didn't purchase the copy in mine.)

That's interesting, because Man in the Ceiling did get a lot of enthusiastic reviews when it first appeared.

Post a Comment