It’s Birds! It’s Planes! It’s…Supermen!

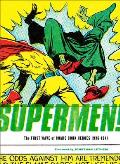

Supermen!: The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes, 1936-1941 promises to fill gaps in “the origins and early development of superheroes and the comic book form.” Editor Greg Sadwoski has assembled an eye-catching collection of stories, magazine covers, and house ads showing unfamiliar faces from the first years of American adventures comics.

There are many familiar names, however. Sadowski appears to have sought out stories by creators who eventually found success with other characters: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Bill Everett, Joe Simon, and Jack Kirby, among others. The collection includes two stories by the execrable Fletcher Hanks, who’s on his way to being the least deserving artist to have his entire oeuvre reprinted. My favorite item is the cover of Fantastic Comics, #3, by Eisner and Lou Fine.

Along the way there are a few landmarks in the development of the American superhero. We see the first caped flying hero (Zator, 1936), the first masked comic-book hero (the Clock, 1936), the first adolescent hero in cape and shorts (Dirk the Demon, 1938—two years before Robin).

But Supermen! is most interesting for what didn’t lead anywhere. All these comics are in the public domain, which of course makes them cheaper to republish. The book is thus a collection of failures—characters and storylines that didn’t attract enough readers to survive. There’s nothing from the firms that became DC and Marvel, and only a couple of items from M.L.J. before it found Archie. In the evolution of the American comic book, these are dead ends.

Seeing what didn’t work or become the norm can be as illuminating as seeing what did. For example, the field was already on its way to male domination when Al Bryant used the pen name “Allison Brant” for a horror story about “Fero, Planet Detective” in May 1940.

We can see publishers figuring out what sells. Silver Streak Comics’s first covers in late 1939 featured a villain—a sort of superhuman Fu Manchu named the Claw. By issue #3 the magazine showed off a hero named Silver Streak instead, and by issue #7 another new hero called Daredevil was fighting the Claw.

Several stories in this volume, especially the earliest, are space-opera science fiction, inspired by Buck Rogers (1928) and Flash Gordon (1934). Their heroes aren’t costumed crime-fighters, but square-jawed men with ordinary abilities in futuristic settings.

The earliest are chapters within continuing stories: the adventures of Dr. Mystic (1936), Dan Hastings (1937), and Cosmic Carson (1940) break off at cliffhangers rather than conclude with triumphs. Clearly, early comic-book publishers and creators were taking their cues from newspaper comics, with their ongoing adventures. But families had newspaper subscriptions, and municipal distribution networks were solid. In contrast, fledgling comic-book publishers probably couldn’t deliver the next installments so reliably, so readers gravitated toward magazines that told complete stories.

Now the industry’s gone back to stretching storylines out over several issues, a form of storytelling possible only because their readership has fallen and their distribution though comic-book shops is narrow but reliable.

There are many familiar names, however. Sadowski appears to have sought out stories by creators who eventually found success with other characters: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Bill Everett, Joe Simon, and Jack Kirby, among others. The collection includes two stories by the execrable Fletcher Hanks, who’s on his way to being the least deserving artist to have his entire oeuvre reprinted. My favorite item is the cover of Fantastic Comics, #3, by Eisner and Lou Fine.

Along the way there are a few landmarks in the development of the American superhero. We see the first caped flying hero (Zator, 1936), the first masked comic-book hero (the Clock, 1936), the first adolescent hero in cape and shorts (Dirk the Demon, 1938—two years before Robin).

But Supermen! is most interesting for what didn’t lead anywhere. All these comics are in the public domain, which of course makes them cheaper to republish. The book is thus a collection of failures—characters and storylines that didn’t attract enough readers to survive. There’s nothing from the firms that became DC and Marvel, and only a couple of items from M.L.J. before it found Archie. In the evolution of the American comic book, these are dead ends.

Seeing what didn’t work or become the norm can be as illuminating as seeing what did. For example, the field was already on its way to male domination when Al Bryant used the pen name “Allison Brant” for a horror story about “Fero, Planet Detective” in May 1940.

We can see publishers figuring out what sells. Silver Streak Comics’s first covers in late 1939 featured a villain—a sort of superhuman Fu Manchu named the Claw. By issue #3 the magazine showed off a hero named Silver Streak instead, and by issue #7 another new hero called Daredevil was fighting the Claw.

Several stories in this volume, especially the earliest, are space-opera science fiction, inspired by Buck Rogers (1928) and Flash Gordon (1934). Their heroes aren’t costumed crime-fighters, but square-jawed men with ordinary abilities in futuristic settings.

The earliest are chapters within continuing stories: the adventures of Dr. Mystic (1936), Dan Hastings (1937), and Cosmic Carson (1940) break off at cliffhangers rather than conclude with triumphs. Clearly, early comic-book publishers and creators were taking their cues from newspaper comics, with their ongoing adventures. But families had newspaper subscriptions, and municipal distribution networks were solid. In contrast, fledgling comic-book publishers probably couldn’t deliver the next installments so reliably, so readers gravitated toward magazines that told complete stories.

Now the industry’s gone back to stretching storylines out over several issues, a form of storytelling possible only because their readership has fallen and their distribution though comic-book shops is narrow but reliable.

No comments:

Post a Comment