Chabon Feeling Torn on Twain

At The Atlantic, novelist Michael Chabon clocks in on the new, worst-epithets-free edition of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. As he notes, he’s criticized that volume for all the applaudable reasons.

At The Atlantic, novelist Michael Chabon clocks in on the new, worst-epithets-free edition of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. As he notes, he’s criticized that volume for all the applaudable reasons.

Yet when reading Twain aloud to his own kids, Chabon found himself changing the text just like Prof. Alan Gribben:

Reading Tom Sawyer occupied the entire summer, and during that time I don't remember wrestling at all with the question of what to say, out loud, with my actual lips and tongue, when my eyes arrived at that strange little word. A cursory search of Google Books suggests that it makes a total of only 10 appearances in the entire book, which is, after all, not told by a backcountry boy in his own dialect but narrated, with a great deal of mock-decorum, in the third person. Ten is probably fairly close to the number of times that I have said "nigger" in my life, never once without some kind of ironizing or sterilizing quotation marks of tone fitted carefully around it, and, somewhat humiliatingly given the choice made by Professor Gribben of Auburn, which I heartily and firmly, piling on, condemn for its cowardice, mealy-mouthedness, and all-consuming fallaciousness, I recall that in those fleeting spots where I encountered the word I would substitute, without missing a beat or losing any literal meaning, "slave." It was no big thing. The kids had no idea that a switcheroo had been run on them.But then comes Huckleberry Finn, because the kids want to hear more about those characters (and Tom Sawyer Abroad is, let’s face it, no substitute).

Chabon faced this awkward situation in a most comfortable setting: with his own kids well before their teens, in a bohemian-bourgeois coastal bedroom, without listeners who might be personally affected by the epithets. (Okay, there’s at least one more comfortable setting to consider the matter: my own, right now, with no big-eyed kids looking up at me and wondering why I haven’t started reading.)

Would the Chabon family stick with Huck Finn as Twain depicted him? Or would they find, like Prof. Gribben, some open compromise with the work? Read the rest of Chabon’s essay for the resolution they found. But don’t miss:

"Hey, Dad," the little guy asked me at one point. "How come if you can't say you-know-what, when you were reading Tom Sawyer you kept saying INJUN Joe, because that's offensive, too."The NewSouth edition of Twain has already dealt with that issue.

Chabon’s essay reminded me of a story I heard about fifteen years ago at a PEN New England forum from an author whose name I’ve tried and failed to recall. Her mother was Native American, her father European-American, and one of her favorite bedtime readalouds was Peter Pan. Her father insisted that she not read that book on her own; she had to wait until he could read it aloud—the book was that special.

Only after this author had grown did she realize that her father was silently editing J. M. Barrie’s passages about the Indians to sand down the offensive stereotypes.

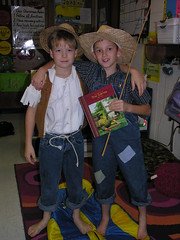

(Photo above courtesy of Judy Baxter, via Flicker under a Creative Commons license.)

3 comments:

To me Chabon and many who commented point to the solution we have always had --- deal with it personally. Years ago when I had a Japanese boy in my class I choked on "Jap" when reading aloud Gary Paulsen's HARRIS AND ME. I explained the situation to the class, but then, even though they seemed unperturbed (probably because they'd never heard of the word as a pejorative before) I was unable to read it again and did indeed edit it out of the rest of my reading of the book. But that was me doing it, not a publisher.

I absolutely am with the commenter who said this yet another instance of mistrusting teachers.

I'm also totally with Lorrie Moore in today's Times. Let Huck and Jim go to college.

I edited Tom Sawyer when I read it to my kids, too. I can't remember how I did it. We didn't read Huck Finn.

I flinched repeatedly in reading Huck Finn to myself, though what annoyed me most was not the n-word but Nigger Jim's character. He was infantile, hanging on Huck (a child) to decide what to do & where to go.

Post a Comment