A New Use for Single Quote Marks?

My final posting for this Oz and Ends PUNCTUATION WEEK concerns a use of quotation marks in fiction that's not standard, as far as I can tell, but might become so.

My final posting for this Oz and Ends PUNCTUATION WEEK concerns a use of quotation marks in fiction that's not standard, as far as I can tell, but might become so.

In a few books, when the text quotes words that no character is saying in the present scene--words that a character has said before, or often says, or that another character imagines being said--that dialogue appears in single quote marks instead of the regular (American) double quote marks.

I first noticed this usage in Scott Turow's Presumed Innocent, published in 1987. Since then, I've kept my eyes open for other books using the same style, and the earliest book in which I've spotted it is Madeleine L'Engle's A Wind in the Door (1973), the first sequel to A Wrinkle in Time. (It may not be coincidence that both those titles came from Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

Here are a couple of passages from A Wind in the Door, chapter three, showing this style in action: The children were all fond of Dr. Louise, and trusted her completely as a physician, but they were not quite sure that she had their parents’ capacity to accept the extraordinary. Almost sure, but not quite. Dr. Colubra had a good deal in common with their parents; she, too, had given up work which paid extremely well in both money and prestige, to come live in this small rural village. (‘Too many of my colleagues have forgotten they are supposed to practice the art of healing. If I don’t have the gift of healing in my hands, then all my expensive training isn’t worth very much.’) She, too, had turned her back on the glitter of worldly success.

And a page later: “You haven’t proven them to me,” Dr. Louise said. “Yet!” She looked slightly ruffled, like a little grey bird. Her short, curly hair was grey; her eyes were grey above a small beak of a nose; she wore a grey flannel suit. “The main reason I think you may be right is that you go to that idiot machine--” she pointed at the micro-electron microscope--“the way my husband used to go to his violin. It was always a lovers’ meeting.“

I wouldn't have used single quote marks in those passages. (And I wouldn't have included the sixth comma in the first passage, or punctuated the clause about the micro-electron microscope within Dr. Louise’s dialogue like that, either.)

Mrs. Murry turned away from her ‘idiot machine.’ “I think I wish I’d never heard of farandolae, much less come to the conclusions--” She stopped abruptly, then said, “By the way, kids, I was rather surprised, just before you all barged into the lab, to have Mr. Jenkins call to suggest that we give Charles Wallace lessons in self-defense.”

I’ve looked in style guides to see if any state this usage is standard, or even a common option, and haven’t found one that recommends treating some quotations differently from others this way. The closest guideline is a Chicago Manual of Style stipulation that in philosophical and linguistic texts certain terms might be enclosed in single quote marks (14th edition, 6.67 and 6.74).

To prepare for this posting, I kept watch for an example of standard use of quote marks in the same situation, and found one in Gail Gauthier's The Hero of Ticonderoga (2001): Mom sighed one of her “I’m trying to keep from killing you” sighs. “No, it does not.”

The dialogue that start “I’m trying...” would be within single quote marks in the system L'Engle and Turow used. That might even be clearer about what's spoken aloud in that scene and what the narrator is recalling from earlier moments. But until that system becomes standard, and readers know how to interpret it on the fly, I think it risks being confusing instead of clarifying.

Has anyone else come across this quirk of punctuation? Has it gotten into any style guides? Does anyone use it all the time?

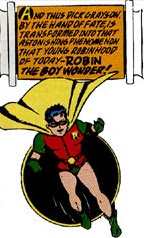

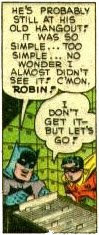

As threatened, here is the first installment of my series-within-a-series that I'm calling "Reasons for Robin." It proposes reasons why the creators of

As threatened, here is the first installment of my series-within-a-series that I'm calling "Reasons for Robin." It proposes reasons why the creators of  Back in

Back in

The Batman Strikes creative team has carried over one element of the modern DCU Batman and Robin stories that's different from the comics of the 1940s through the 1980s: nowadays, Robin is often the more mature partner.

The Batman Strikes creative team has carried over one element of the modern DCU Batman and Robin stories that's different from the comics of the 1940s through the 1980s: nowadays, Robin is often the more mature partner.