How Artemis Fowl Goes Graphic

When Eoin Colfer's Artemis Fowl was first published in 2001, Miramax/Hyperion marketed it as a counterpoint to Harry Potter. Of course, back then every book from presidential memoirs on down was being compared to Harry Potter. At least Colfer had actually written in the same genre as J. K. Rowling.

When Eoin Colfer's Artemis Fowl was first published in 2001, Miramax/Hyperion marketed it as a counterpoint to Harry Potter. Of course, back then every book from presidential memoirs on down was being compared to Harry Potter. At least Colfer had actually written in the same genre as J. K. Rowling.

Artemis is an anti-hero, angling to be a master criminal rather than a magical law enforcer. He has vast resources and loyal support. Though eventually we learn he's as hungry for a happy family as Harry is, long before then the reader might feel that what Artemis deserves most is a punch in the face.

Perhaps as a result, Colfer and Rowling used different storytelling strategies. The Harry Potter novels stick closely to Harry's point of view. When they narrate events through into someone else's eyes, as in the start of HP4, there must be a very important reason: in that case, to show Voldemort killing so we understand the stakes.

In contrast, Artemis Fowl was never all about Artemis Fowl. Yes, the story starts by tracking his scheme to steal fairy secrets and gold, but Colfer shifts to narrating over the shoulder of a young fairy law enforcer named Holly Short--a more upright and sympathetic character. For the rest of the novel, the point of view bounces among different characters, including Holly's gruff but dedicated boss, one of Artemis's household servants, and a dwarf expert in breaking and entering.

In contrast, Artemis Fowl was never all about Artemis Fowl. Yes, the story starts by tracking his scheme to steal fairy secrets and gold, but Colfer shifts to narrating over the shoulder of a young fairy law enforcer named Holly Short--a more upright and sympathetic character. For the rest of the novel, the point of view bounces among different characters, including Holly's gruff but dedicated boss, one of Artemis's household servants, and a dwarf expert in breaking and entering.

Comic books have shifted like that for years. The visual dimension makes it easier for readers to follow the change: we turn the page, see a new character in a new locale, and we get it. We don't even need "Meanwhile,..." captions anymore.

In the last couple of decades, the omniscient narrator who used to fill the captions of comic books with bombastic explanations has disappeared. Instead, most captions are in the first-person, present-tense voice of the main character. That technique has developed its own symbolic grammar: those captions often have different colors, symbols, and fonts for different characters. That lets comics delineate two or more points of view in the same scene, even the same panel.

In the last couple of decades, the omniscient narrator who used to fill the captions of comic books with bombastic explanations has disappeared. Instead, most captions are in the first-person, present-tense voice of the main character. That technique has developed its own symbolic grammar: those captions often have different colors, symbols, and fonts for different characters. That lets comics delineate two or more points of view in the same scene, even the same panel.

Indeed, I think a great potential strength of the comics form is its ability to show two parties working against each other without making readers take sides (if the creators wish to remain neutral, of course).

Artemis Fowl: The Graphic Novel uses that comics technique to replicate the prose novel's shifting points of view. Contrast the caption in the first of the four stacked panels above, its font and coloring, with the caption in panel three. The first is the fairy Holly's thought as she searches for her helmet. The second is Artemis's reflection as he sees Holly about to punch him in the face. The comics form offers both characters' thoughts in the same scene.

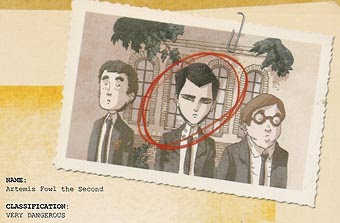

Another comic-book technique that pops up in Artemis Fowl: The Graphic Novel is the character profile; the top illustration is a bit of Artemis's. Each full-page profile offers a combination of words and image to introduce a magical creature or locale. Novels can't lay out such information without breaking the narrative flow, but such profiles are a comic-book tradition. DC publishes a whole series offering such dossiers on its heroes and villains: Secret Files. Another inspiration is probably card games like Magic: The Gathering. (It's no surprise that similar pages appear in The Spiderwick Chronicles; coauthor and artist Tony DiTerlizzi worked on Magic cards.)

There are other big points of overlap between Colfer's Artemis Fowl and comic-book adventures:

- The story highlights advanced technology, even in the fairy world, rather than old-fashioned magic.

- The characters are all flat, in the E. M. Forster sense, with clear goals and little internal conflict or growth.

- A great many problems are solved through physical action. Violence, in fact--though never, heaven forbid, fatal violence. Just a punch in the face here and there.

Bottom line: A novel that reads a lot like a comic book makes a good comic book.

2 comments:

One mistake. The fairy, Holly, should be about 1 meter long, that means shorter than Artemis

The comic’s creators probably decided that showing Holly and other creatures at about the same size as Artemis would work better visually.

Post a Comment