The Mummy Turns: The Professor’s Daughter

Our mummy monster myth seems to be relatively recent. As Paula Guran's essay on DarkEcho traces, the tradition in English literature seems to go back to Arthur Conan Doyle's stories "The Ring of Thoth" (1890) and "Lot No. 249" (1892), and Bram Stoker's novel The Jewel of Seven Stars (1906). Though other authors, many of them French, had written a variety of fantastic stories about mummies, those three tales from late Victorian London seem to have codified the myth.

Our mummy monster myth seems to be relatively recent. As Paula Guran's essay on DarkEcho traces, the tradition in English literature seems to go back to Arthur Conan Doyle's stories "The Ring of Thoth" (1890) and "Lot No. 249" (1892), and Bram Stoker's novel The Jewel of Seven Stars (1906). Though other authors, many of them French, had written a variety of fantastic stories about mummies, those three tales from late Victorian London seem to have codified the myth.

In 1932, after Dracula was a big hit, Universal Pictures seized on that tradition to make The Mummy with Boris Karloff. (Hollywood had produced several short movies about mummies in the 1910s and '20s, but those were comedies, not horror adventures.) Other mummy movies followed that one, right through this decade, cementing the myth in our culture.

These horror tales share a basic narrative: Ancient Egyptian monarch or priest is brought back to life, is upset about Westerners raiding his tomb or some other affront, and wreaks more havoc than a dessicated corpse wrapped in cloth should be able to wreak. A recurring plot element is that the mummy seeks his (or, in the rare case, her) lost love, who in an astonishing coincidence is closely connected to the archeologist who did the tomb-raiding. It's easy to read colonialist fear and guilt into that part of the tale. The Professor's Daughter, the 2007 Cybils Award designee as Best Graphic Novel for Teens, borrows some of that mummy myth and turns the rest of its head. A corpse in bandages named Imhotep IV woos Lillian Bowell, daughter of the scientist who has brought him to London sometime in the late 1800s. The young woman even reminds the mummy of his dead wife. But in this tale Lillian loves him back. And why not? Imhotep's charming and devoted. The only tyrant in her life is her father.

The Professor's Daughter, the 2007 Cybils Award designee as Best Graphic Novel for Teens, borrows some of that mummy myth and turns the rest of its head. A corpse in bandages named Imhotep IV woos Lillian Bowell, daughter of the scientist who has brought him to London sometime in the late 1800s. The young woman even reminds the mummy of his dead wife. But in this tale Lillian loves him back. And why not? Imhotep's charming and devoted. The only tyrant in her life is her father. When Imhotep expresses his love for Lillian, Prof. Bowell replies, "You are the property of the British Museum. You are dead. Stay out of this!" Victorian propriety is an important element of the story, the atmosphere to be upended over and over by slapstick action and sudden death.

When Imhotep expresses his love for Lillian, Prof. Bowell replies, "You are the property of the British Museum. You are dead. Stay out of this!" Victorian propriety is an important element of the story, the atmosphere to be upended over and over by slapstick action and sudden death.

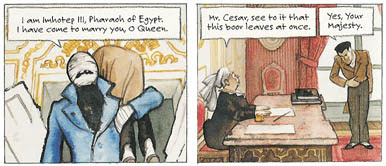

Imhotep IV and Lillian run away, only to fall into the hands of someone else who wishes to marry her, someone far less gentlemanly than Imhotep IV. That's his father, Imhotep III, also a mummy, but with less well preserved teeth. He's the classic monster: arrogant, angry, and unstoppable. The plot twists around on itself like a long bandage. There are jail breaks and dream sequences and murder trials and imprisonment in the Tower of London. Queen Victoria herself makes an appearance as the older mummy seeks a mate worthy of his rank.

The plot twists around on itself like a long bandage. There are jail breaks and dream sequences and murder trials and imprisonment in the Tower of London. Queen Victoria herself makes an appearance as the older mummy seeks a mate worthy of his rank. In fact, though we root for Imhotep IV and Lillian to gain a happy ending, I think Imhotep III eventually carries away this story. In his own brutal way, he wants the best for his son as well as only the best for himself. He's also ruthless, killing at least two men, probably many more. But of course a story about mummies has death running through it from the beginning, doesn't it?

In fact, though we root for Imhotep IV and Lillian to gain a happy ending, I think Imhotep III eventually carries away this story. In his own brutal way, he wants the best for his son as well as only the best for himself. He's also ruthless, killing at least two men, probably many more. But of course a story about mummies has death running through it from the beginning, doesn't it?

All but four pages of this book have the same layout of six equal-sized panels. (There's a reason for each of those four deviations from the pattern, in two cases important plot turns.) The art's lines are generally soft, the colors generally muted. As the story's wild activities appear in that gentle style, it becomes the visual equivalent of a deadpan, both softening the violence and heightening the humor.

The script for The Professor's Daughter was by Joann Sfar, who also writes and illustrates the Little Vampire books. The art was by Emmanuel Guibert, and a selection from his London sketchbook appears in the back. (Such add-ons seem unique to graphic novels; we don't see research notes, discarded chapters, or character sketches at the back of other types of books.) This comic was originally published in France in 1997, a decade before it was translated by Alexis Siegel and published in the US.

As before, I recommend Angie Thompson's summary of the charms of The Professor's Daughter. This month Cynthia Leitich Smith's blog ran an interview with artist Emmanuel Guibert by Anita Loughrey that reads like pulling teeth.

1 comment:

Hi J. L. Bell,

Thank you for the mention on your most excellent blog. I have added you to my favourites so I can pop back and visit from time to time.

I agree Emmanuel was a man of very few words. But, what he did write was very funny and made me laugh.

What we need to remember was he was reading and writing in English rather than in French and he is primarily an illustrator. His illustrations are amazing.

The interview I did with Marc Boutavant, which is yet to appear on Cynthis's Blog, was mainly answered through illustrations. That will be one to look out for.

Best wishes,

Anita Loughrey

Post a Comment