So What's "Temporal Perspective"?

Lee of the Mortal Ghost blog novel sent this comment to one of last week’s posting:

Lee of the Mortal Ghost blog novel sent this comment to one of last week’s posting:Will you please explain what you mean by 'temporal perspective'?

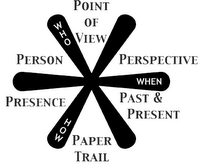

Which left me confused because I hadn’t used that term recently. But by using the search function, I found that Lee must have followed links back to a posting about narrative voices last year. That mentioned a presentation I gave at last year’s SCBWI New England conference about the parameters of narrative voice in fiction.

One of those parameters, I posit, is Perspective. (I gave all six parameters labels that begin with P, just because.) In my thinking, Perspective refers to the amount of time that’s passed between the events in a story and the storytelling itself. Does the narrator indicate that he or she knows how the story ends? Is the narrator looking back on the events from years later? Does the narrator’s Perspective shift with events, as in an epistolary novel?

In my talk I used the openings of three novels to show different common Perspectives--

Immediate“Too many!” James shouted, and slammed the door behind him.

That appears to be the default Perspective today: get us right into the action, with no hint that the narrator has any knowledge of what’s to come. (Curiously, this opening suggests that James is the character with a problem; Cooper does a deft shift in the next paragraph to put us in Will’s head instead. But that’s a matter of what I call Point of View.)

“What?” said Will.

“Too many kids in this family, that’s what. Just too many.” James stood fuming on the landing like a small angry locomotive, then stumped across to the window-seat and stared out at the garden.--Susan Cooper, The Dark Is Rising (1973)

RecentI don’t know just why I’m telling you all this. Maybe you’ll think I’m being silly. But I’m not, really, because this is important. You see, it was different! It wasn’t just because it was Jack and I either--it was something more than that.

This narrator does know what will happen in her story. But she’s still close enough to those events to believe that they’re really important, and deep. This story about adolescence thus comes from an adolescent Perspective. Other novels about that time in life are written from a more distant, adult Perspective. I think that’s one of the significant differences between true YA fiction and coming-of-age novels for adult readers.--Maureen Daly, Seventeenth Summer (1942)

RetrospectiveMy brother Tom and eldest brother Sweyn arrived home for summer vacation on Sunday, June 5, 1898. I remember the date very well because, just two weeks later, the entire town of Park City was destroyed by the worst fire in the history of Utah.

This narrator not only knows what’s upcoming two weeks after the opening moment, but is also distant enough from those events to say, “I remember the date” and “the history of Utah.” This Perspective adds to the sense that the novel might be the true recollection of an aged Utahan. And it hints at entertaining chaos to come.--John D. Fitzgerald, The Great Brain Reforms (1973)

Telling a story in diary form forces an author to adopt a certain Perspective: each diary entry describes what the character writing believes and feels at that moment, not while the events take place, nor the next day with more knowledge. Often this can interfere with a sense of immediacy and produce less suspense for readers. In Beka Cooper: Terrier, Tamora Pierce wrestles with this problem on page 364 by having her heroine write:I must write about today, because so much has happened. I think the only way I can write it is to write of my watch, and do so as I lived it, without knowing how it will end.

As I wrote earlier, eschewing the diary format for an immediate Perspective would have let Pierce launch straight into the episode without this apology for doing so.

Lee added in an email:Have you done any reading in neuroscience or cosmology regarding time? Terribly complex for someone like myself, but fascinating nevertheless. I'm currently working my way through Benjamin Libet's Mind Time: The Temporal Factor in Consciousness.

No, I haven’t explored that far, and I’m not sure my concept of Perspective is up to that level of sophistication. It’s simply a parameter writers might choose when considering various ways to tell a story. The same events can look quite different from the distance of a few minutes, a day, a year, or many years. One story might work best with one Perspective while another story wouldn’t work that way at all. And breaking out of the Perspectives we’re used to (as in, say, the movies Groundhog Day and Memento) can be very powerful.

2 comments:

Thanks for this. I believe it's similar,though not identical, to what John Gardner calls 'psychic distance': 'By psychic distance we mean the distance the reader feels between himself and the events in the story.' (The Art of Fiction, Vintage pb, p. 111). He goes on to list examples of decreasing distance. However, your temporal perspective isolates the time factor - a useful lens - whereas Gardner includes other elements. However, I like his comparison to the dollying of a camera and his warning about clumsy shifts; and his point about the subtle effects a skilled writer can achieve through controlled shifts.

Yes, I believe three or four of my parameters can increase or decrease "psychic distance." Good connections.

I also agree that keeping an eye on reader expectations and controlling shifts in those parameters, or other elements of writing, is key to creating energy in storytelling. Like other forms of art, fiction gains power from the play of the expected and the unexpected, patterns and breaking patterns.

Now if it were so easy to realize that sort of vision on paper...

Post a Comment