The Pictures and the Prose

When the National Book Award nominations were announced earlier in the fall, Gene Yang's American Born Chinese received extra attention because it was the first graphic novel to receive that honor. Not all that attention was favorable, and Wired's "Luddite" columnist Tony Long complained:

When the National Book Award nominations were announced earlier in the fall, Gene Yang's American Born Chinese received extra attention because it was the first graphic novel to receive that honor. Not all that attention was favorable, and Wired's "Luddite" columnist Tony Long complained:...as literature, the comic book does not deserve equal status with real novels, or short stories. It's apples and oranges.

I have tried writing "a real novel" or two or seventeen in my time, and I've tried writing and drawing a couple of "real comic books." They are indeed two very different media. But if the level of difficulty is the criterion for judging their value, I'm taking the easy road by sticking to prose.

If you've ever tried writing a real novel, you'll know where I'm coming from. To do it, and especially to do it well enough to be nominated for this award,...is exceedingly difficult.

In a most classy move, Yang replied on his publisher's First Second blog with praise for...another nominee! (And yesterday's eventual winner, Octavian Nothing, by M. T Anderson). Yang wrote:One of the most intriguing aspects of the book (for me, at least) is Anderson's use of visual storytelling devices. For example, Anderson uses different fonts and font styles to communicate time, place, and emotion.

My only quibble with this argument is that, while "modern printing technology" makes the mix of prose and art much more cheap and flexible than it's been in times past, that novelistic technique is about as old as Anderson's Octavian character, if not older.

There are other, more striking, examples. In an early chapter, the protagonist opens the door to a forbidden room and is startled by a sign hanging on the wall, a sign that reveals the secret behind the peculiarities of his existence. That sign is DRAWN in the middle page. It slaps you in the face on the page turn, much as it does Octavian when he opens the door.

Toward the end of the book (here comes a spoiler, so go away until you've actually read it), after Octavian suffers a gruesome personal tragedy, entire passages of the book are scribbled out with what looks to be a crow quill pen. The pages of angry lines and ink splotches communicate as much or more about Octavian's state of mind as the paragraphs that came before.

No one would argue that M.T. Anderson's book is not a novel, but does Anderson's inclusion of graphic devices diminish the "novel-ness" of Octavian Nothing? Does it make Anderson less of a "novelist"?

Not to me. To me, it shows that he committed to the telling of his story above all else, and that he is willing to use whatever devices modern printing technology affords to communicate effectively.

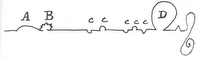

As this online exhibit from the Glasgow University Library shows, Laurence Sterne interrupted what little story there was in his Tristram Shandy with such devices as a marbled page, a black page, and a crooked line like this: And how about that stately, plump S at the start of James Joyce's Ulysses? I'm pretty sure Tristram Shandy and Ulysses are "real novels" within the English literary tradition. But they're not plain prose.

And how about that stately, plump S at the start of James Joyce's Ulysses? I'm pretty sure Tristram Shandy and Ulysses are "real novels" within the English literary tradition. But they're not plain prose.

2 comments:

Doing anything worthwhile well isn't easy. Writing excellent prose isn't easy. Creating excellent comics isn't easy. If this guy's "easy" judgement that you cite is truly his assessment, then he doesn't know what he's talking about.

I, too, have written prose and created comics. That I've chosen to draw more comics and consider myself primarily a cartoonist isn't because it's easier than prose. It's because that's the way I've found that seems natural for me to communicate stories.

I'm not sure one is easier. They both have different challenges, the most obvious being that you gotta be able to draw to create comics. Comics generally takes much, MUCH longer.

I have no problem with Gene Yang's book being nominated, and I say more power to him.

Having said that, however, comics are a different medium than prose, and I can see clear arguments why comics should not be included in awards for prose. Plays aren't considered for movie awards. Poems aren't considered for music awards. Radio isn't considered for television awards. All these pairs of media have things in common. Yet each is distinct from the other just as comics as a medium is distinct from prose as a medium.

On the other hand, the line between comics and illustrated books often is quite blurry in the way that the distinction between radio and television is not. Just taking one example of many, is Sendak's Higglety Pigglety Pop a picture book or a comic book? Well, it's both. And now that "traditional" book publishers are publishing so many comics, the lines between comics and prose are blurring on several different fronts.

I think this is all good. It's certainly good for comics and it doesn't hurt prose at all.

Best,

Eric Shanower

I agree that it makes sense to consider graphic novels/comics separately from other prose novels, just as we consider prose novels different from poetry or nonfiction.

It's clear from one glance that Octavian Nothing and Tristram Shandy are mostly prose, though they incorporate graphic elements. American Born Chinese and Age of Bronze are mostly pictures, judging by the amount of space they take up on--though their words are a much more important ingredient than the text in, say, Winsor McKay's Little Nemo in Slumberland.

In this regard, it's interesting to note that the National Book Award goes to "Young People's Literature," not to fiction, nonfiction, poetry (the three other categories, with "adult" being assumed), or any other classification. Recent nominations in that category have pitted nonfiction against fiction, poetry against prose. And now prose against comics.

(As for whether prose or comics is easier, I was writing only from my own experience, with my own mix of talents. But that subjectivity is another reason to reject Gene Long's implication that what's more difficult is ipso facto more worthy of respect. If so, I really should be trying to express myself at the ballet because I have the least aptitude for that art.)

Post a Comment