The Significance of “Playin’ Hookey”

“Playin’ Hookey,” credited to director Anthony Mack (IMDB; YouTube; The Lucky Corner; Dave Lord Heath), is not one of the more inspired Our Gang comedies. Like a number of the series’ other silent shorts, it feels like two half-developed stories with only a loose connection between them.

In the first half, Joe Cobb’s dog Pansy gets blamed for scaring chickens and destroying property. Pansy’s misbehavior is actually the fault of Joe’s little brother Wheezer, played by Bobby Hutchins. In this stretch of the series, Wheezer was an unstoppable engine of chaos.

Joe’s dad prepares to kill the dog with a shotgun. [Kids’ comedy, folks!] But Joe unloads the gun and tells Pansy to play dead. He sneaks her away and tries to find her refuge with Farina and his little sister, portrayed by Sunny and Jannie Hoskins. Jannie’s character is called Zuccini because almost all the series’ black kids got assigned food names; usually Farina’s sister was named Mango, but other exceptions were Arnica and Trellis.

Then a police chase happens nearby. All the big kids run to see. That action turns out to be a scene from a movie being filmed on the streets of Culver City. By a stroke of luck, the movie crew is looking for a dog that can play dead. Joe offers to bring Pansy to the studio for $5. His pals sneak in after him.

In fact, the gang sneaks into the All-American Studios by pretending to be dummies in a truck, the exact same way the gang got into the West Coast Studios in “Dogs of War” (1923). That short also began as one story—an elaborate parody of trench warfare—and turned into a romp through movie sets. William Gillespie appeared in both films, in the first as a harried director and in the second as a harried actor.

For the rest of “Playin’ Hookey,” the kids and dog run around the studio, disrupt scenes being filmed in a variety of genres, and tangle with actors and security guards. At one odd moment we see the Triceratops costume from Laurel and Hardy’s “Flying Elephants,” filmed in early May 1927. Indeed, that Triceratops gets more screen time in “Playin’ Hookey” than in the surviving “Flying Elephants.”

Eventually, the action shifts to a set in a kitchen filled with custard pies and buns, the latter for some reason being filled with gunpowder. Charlie Hall plays a comedian made up to look as much like Chaplin as possible without risking a lawsuit. There’s a line of cops in old-fashioned helmets and long coats, looking nothing like the police officers earlier in this film. In short, we’ve entered a travesty of the Keystone Studio as it was more than a decade before.

The kids run onto that set. They see the comedian being chased by a knife-wielding chef. The gang’s current freckled boy—skinny, bespectacled Jay R. Smith—picks up a pie and throws it at the chef. Soon the other kids are tossing pies, as well as those exploding buns. Chaos ensues, but not hilarity.

Critics might quibble that this isn’t a full pie fight since nobody throws anything back at the kids. But the action does include the usual detail of pastry flying wild and hitting people not part of the initial conflict. Among the adults struck with pies are those Keystone-style cops, an actress played by Dorothy Coburn, and her hairdresser played by Edith Fortier (usually on set as the Hoskinses’s aunt and chaperone).

Eventually the studio security team led by Tiny Sandford catches the gang and literally throws them out of the studio. We never learn what will happen to Pansy. That concern was back in the first half of the movie, after all.

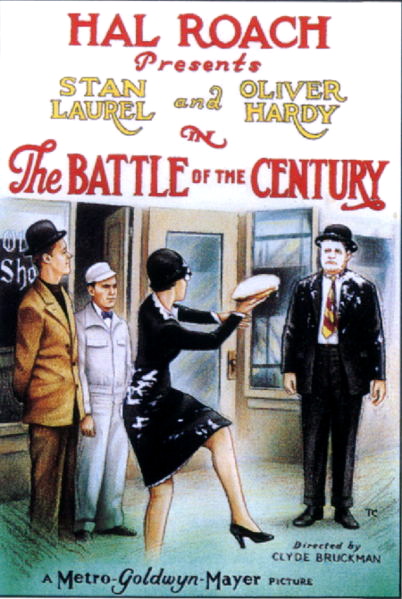

“Playin’ Hookey” isn’t a very interesting film. Even the backstage look at the Roach lot is unrevealing since the set-ups are so artificial; “Dogs of War” shows more. But “Playin’ Hookey” is significant as an example of a pie fight shortly before Laurel and Hardy’s lauded “Battle of the Century,” reflecting how the studio viewed that trope (IMDB; YouTube).

But wait! you say. “The Battle of the Century” is a 1927 film. “Playin’ Hookey” is listed as from 1928.

Quite true, I reply. But “Playin’ Hookey” was made in the summer of 1927 while “The Battle of the Century” went into production on 5 October. (For a complex discussion of when “Playin’ Hookey” was made, see its page at the Lucky Corner. For equivalent information about “The Battle of the Century,” see Dave Lord Heath’s page.)

MGM released “The Battle of the Century” on the very last day of 1927. Roach’s previous distributor, Pathé, had the rights to “Playin’ Hookey,” and it held that picture back until the first day of 1928. As a result, its significance has been masked.

“The Battle of the Century” starts as a boxing movie, inspired by the Gene Tunney–Jack Dempsey fight of 22 Sept 1927. In talking about where to go from there, someone on the writing staff suggested a pie fight.

The Hal Roach Studio was small and friendly. Hall, Coburn, Sandford, and other players in the Our Gang picture also acted in Laurel and Hardy movies that summer. Stan Laurel and his fellow writers had to have known about the making of “Playin’ Hookey.”

That picture reflected the dominant industry thinking about pie fights at the time: they were hokum, a relic of the previous decade, entertaining only for kids. A couple of years later, Laurel told Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times that simply throwing pies “really had passed out with Keystone”—exactly as depicted in the Our Gang film.

Looking for something new, Laurel rethought the trope. “We made every one of the pies count,” he said. The scene wasn’t just messy chaos. It was messy chaos that built up gradually from character interactions. “The Battle of the Century” was a hit, and it resurrected the pie fight as nostalgic fun.

COMING UP: A changed Hollywood.

In the first half, Joe Cobb’s dog Pansy gets blamed for scaring chickens and destroying property. Pansy’s misbehavior is actually the fault of Joe’s little brother Wheezer, played by Bobby Hutchins. In this stretch of the series, Wheezer was an unstoppable engine of chaos.

Joe’s dad prepares to kill the dog with a shotgun. [Kids’ comedy, folks!] But Joe unloads the gun and tells Pansy to play dead. He sneaks her away and tries to find her refuge with Farina and his little sister, portrayed by Sunny and Jannie Hoskins. Jannie’s character is called Zuccini because almost all the series’ black kids got assigned food names; usually Farina’s sister was named Mango, but other exceptions were Arnica and Trellis.

Then a police chase happens nearby. All the big kids run to see. That action turns out to be a scene from a movie being filmed on the streets of Culver City. By a stroke of luck, the movie crew is looking for a dog that can play dead. Joe offers to bring Pansy to the studio for $5. His pals sneak in after him.

In fact, the gang sneaks into the All-American Studios by pretending to be dummies in a truck, the exact same way the gang got into the West Coast Studios in “Dogs of War” (1923). That short also began as one story—an elaborate parody of trench warfare—and turned into a romp through movie sets. William Gillespie appeared in both films, in the first as a harried director and in the second as a harried actor.

For the rest of “Playin’ Hookey,” the kids and dog run around the studio, disrupt scenes being filmed in a variety of genres, and tangle with actors and security guards. At one odd moment we see the Triceratops costume from Laurel and Hardy’s “Flying Elephants,” filmed in early May 1927. Indeed, that Triceratops gets more screen time in “Playin’ Hookey” than in the surviving “Flying Elephants.”

Eventually, the action shifts to a set in a kitchen filled with custard pies and buns, the latter for some reason being filled with gunpowder. Charlie Hall plays a comedian made up to look as much like Chaplin as possible without risking a lawsuit. There’s a line of cops in old-fashioned helmets and long coats, looking nothing like the police officers earlier in this film. In short, we’ve entered a travesty of the Keystone Studio as it was more than a decade before.

The kids run onto that set. They see the comedian being chased by a knife-wielding chef. The gang’s current freckled boy—skinny, bespectacled Jay R. Smith—picks up a pie and throws it at the chef. Soon the other kids are tossing pies, as well as those exploding buns. Chaos ensues, but not hilarity.

Critics might quibble that this isn’t a full pie fight since nobody throws anything back at the kids. But the action does include the usual detail of pastry flying wild and hitting people not part of the initial conflict. Among the adults struck with pies are those Keystone-style cops, an actress played by Dorothy Coburn, and her hairdresser played by Edith Fortier (usually on set as the Hoskinses’s aunt and chaperone).

Eventually the studio security team led by Tiny Sandford catches the gang and literally throws them out of the studio. We never learn what will happen to Pansy. That concern was back in the first half of the movie, after all.

“Playin’ Hookey” isn’t a very interesting film. Even the backstage look at the Roach lot is unrevealing since the set-ups are so artificial; “Dogs of War” shows more. But “Playin’ Hookey” is significant as an example of a pie fight shortly before Laurel and Hardy’s lauded “Battle of the Century,” reflecting how the studio viewed that trope (IMDB; YouTube).

But wait! you say. “The Battle of the Century” is a 1927 film. “Playin’ Hookey” is listed as from 1928.

Quite true, I reply. But “Playin’ Hookey” was made in the summer of 1927 while “The Battle of the Century” went into production on 5 October. (For a complex discussion of when “Playin’ Hookey” was made, see its page at the Lucky Corner. For equivalent information about “The Battle of the Century,” see Dave Lord Heath’s page.)

MGM released “The Battle of the Century” on the very last day of 1927. Roach’s previous distributor, Pathé, had the rights to “Playin’ Hookey,” and it held that picture back until the first day of 1928. As a result, its significance has been masked.

“The Battle of the Century” starts as a boxing movie, inspired by the Gene Tunney–Jack Dempsey fight of 22 Sept 1927. In talking about where to go from there, someone on the writing staff suggested a pie fight.

The Hal Roach Studio was small and friendly. Hall, Coburn, Sandford, and other players in the Our Gang picture also acted in Laurel and Hardy movies that summer. Stan Laurel and his fellow writers had to have known about the making of “Playin’ Hookey.”

That picture reflected the dominant industry thinking about pie fights at the time: they were hokum, a relic of the previous decade, entertaining only for kids. A couple of years later, Laurel told Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times that simply throwing pies “really had passed out with Keystone”—exactly as depicted in the Our Gang film.

Looking for something new, Laurel rethought the trope. “We made every one of the pies count,” he said. The scene wasn’t just messy chaos. It was messy chaos that built up gradually from character interactions. “The Battle of the Century” was a hit, and it resurrected the pie fight as nostalgic fun.

COMING UP: A changed Hollywood.

1 comment:

It seems appropriate that footage from “Playin’ Hookey” makes up a big part of the opening for Comedy Capers, a television show made up of a mishmash of footage from silent comedies. That short was itself a mix of 1910s and 1920s styles spoofing earlier comedians.

Post a Comment