“Uncomfortable with how he came to have it”

From Eula Biss’s essay “White Debt” in yesterday’s New York Times Magazine:

This anecdote reminded me of time nearly a decade ago when I accompanied Godson and Godson’s Brother, along with their parents, to Plimoth Plantation. The boys were about six, and they enjoying tearing around the recreated meetinghouse/fort in that museum village, peering down the cannon barrels out across the stockade.

Then Godson’s Brother stopped and told me very seriously that if he were able to go back to Plymouth in 1627, he would give the Natives rifles. (Actually, he said “wifles,” because he was still having trouble with some consonants.) I rather hoped he was thinking about establishing a fairer balance of power rather than more deadly fighting, especially since some of my ancestors would have been on the other side of those mythical rifle shots. Again, comfort and discomfort, and a broader perspective from today’s kids.

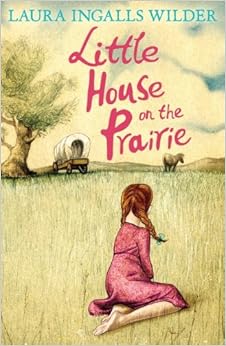

I read several hundred pages of Little House on the Prairie to my 5-year-old son one day when he was home sick from school. Near the end of the book, when the Ingalls family is reckoning with the fact that they built their little house illegally on Indian Territory, and just after an alliance between tribes has been broken by a disagreement over whether or not to attack the settlers, Laura watches the Osage abandoning their annual buffalo hunt and leaving Kansas. Her family will leave, too.This five-year-old’s reaction could not have been solely based on what Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter wrote in that book, which reflects previous centuries’ views of that conflict (Ma Ingalls’s even more old-fashioned than Pa’s and the authors’). That suggests that, at least for him, he’s picking up a broader perspective about the long, often fatal conflict over land in North America.

At this point, my son asked me to stop reading.

“Is it too sad?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “I just don’t need to know any more.” After a few moments of silence, he added, “I wish I was French.”

The Indians in Little House are French-speaking, so I understood that my son was saying he wanted to be an Indian. “I wish all that didn’t happen,” he said. And then: “But I want to stay here, I love this place. I don’t want to leave.” He began to cry, and I realized that when I told him Little House was about the place where we live, meaning the Midwest, he thought I meant it was about the town where we live and the house we had just bought.

Our house is not that little house, but we do live on the wrong side of what used to be an Indian boundary negotiated by a treaty that was undone after the 1830 Indian Removal Act. We live in Evanston, Ill., named after John Evans, who founded the university where I teach and defended the Sand Creek massacre as necessary to the settling of the West. What my son was expressing — that he wants the comfort of what he has but that he is uncomfortable with how he came to have it — is one conundrum of whiteness.

This anecdote reminded me of time nearly a decade ago when I accompanied Godson and Godson’s Brother, along with their parents, to Plimoth Plantation. The boys were about six, and they enjoying tearing around the recreated meetinghouse/fort in that museum village, peering down the cannon barrels out across the stockade.

Then Godson’s Brother stopped and told me very seriously that if he were able to go back to Plymouth in 1627, he would give the Natives rifles. (Actually, he said “wifles,” because he was still having trouble with some consonants.) I rather hoped he was thinking about establishing a fairer balance of power rather than more deadly fighting, especially since some of my ancestors would have been on the other side of those mythical rifle shots. Again, comfort and discomfort, and a broader perspective from today’s kids.

No comments:

Post a Comment