Our Cancers, Ourselves

Today Nature announced an agreement between the National Institutes of Health and the heirs of Henrietta Lacks, the woman whose cancerous cells, denoted “HeLa,” have proved remarkably long-lived and therefore useful for medical research.

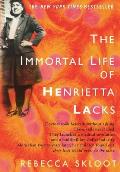

As described by Rebecca Skloot in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Lacks had a hard life even before developing that virulent cancer. Her family received no compensation and minimal recognition for her contribution to modern medicine. Under the new agreement, family members will be on a committee that considers requests for research and publication of genetic data using the HeLa cells, restoring the principle of people being in charge of their own tissue and biological information.

There’s an irony in this situation, of a sort I first noticed in another case of horrible medical care given to an African-American in Jim-Crow America. In 1947 San Francisco doctors diagnosed Elmer Allen, a Pullman porter, with bone cancer. Considering his leg (or simply Allen himself) untreatable, they injected that leg with plutonium in order to study how the radioactive element affected the human body. Three days after the injection, the doctors amputated that leg and sent him home to die.

Allen lived for forty-four more years. He died in 1991, one year before reporter Eileen Welsome connected him to the records of the plutonium experiment. He never knew how badly his doctors and government had treated him, but Allen was reportedly bitter all his life about having lost his leg and career. Yet that amputation, as heartless as it was, may in fact have saved him from the bone cancer.

Similarly, Henrietta Lacks’s descendants view her undying cells as a surviving part of her, yet if she had had the option of killing or getting rid of that cancer she would surely have been glad to take it, and to think of those cells as something apart from herself.

As described by Rebecca Skloot in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Lacks had a hard life even before developing that virulent cancer. Her family received no compensation and minimal recognition for her contribution to modern medicine. Under the new agreement, family members will be on a committee that considers requests for research and publication of genetic data using the HeLa cells, restoring the principle of people being in charge of their own tissue and biological information.

There’s an irony in this situation, of a sort I first noticed in another case of horrible medical care given to an African-American in Jim-Crow America. In 1947 San Francisco doctors diagnosed Elmer Allen, a Pullman porter, with bone cancer. Considering his leg (or simply Allen himself) untreatable, they injected that leg with plutonium in order to study how the radioactive element affected the human body. Three days after the injection, the doctors amputated that leg and sent him home to die.

Allen lived for forty-four more years. He died in 1991, one year before reporter Eileen Welsome connected him to the records of the plutonium experiment. He never knew how badly his doctors and government had treated him, but Allen was reportedly bitter all his life about having lost his leg and career. Yet that amputation, as heartless as it was, may in fact have saved him from the bone cancer.

Similarly, Henrietta Lacks’s descendants view her undying cells as a surviving part of her, yet if she had had the option of killing or getting rid of that cancer she would surely have been glad to take it, and to think of those cells as something apart from herself.

2 comments:

hi John,

I'm reading "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" right now. It's quite a story.

Interesting news about her descendants finally being included in decisions made about the use of her surviving cells.

It's pretty weird that the cells that have proven so useful to medical research are monsters. Though they are genetically Ms Lacks the defects in those cells led them to torture the poor woman to death. The same (?) defects that killed Ms Lacks have made the cells extraordinarily hardy in the lab.

-Glenn

Yes, there's a lot of irony involved in how Lacks's cells could be so harmful and yet so useful.

The question of justice also brings up ironies. It appears that Lacks's medical treatment in 1951 was no worse because she was African-American; doctors couldn't do much for anyone with such powerful cancer cells. And the use of those cells was also typical of how physicians behaved then. They undoubtedly provided for the greater good. On the other hand, it's clear that Lacks and her family suffered from the broader racism in American society, an injustice we now want to acknowledge and, at least some of us, repair.

The Lacks descendants won't profit financially from the new arrangement, in part because the U.S. Supreme Court has just ruled that people's naturally occurring genetic code can't be patented. Some of the Lacks family were already on record saying they didn't want money, just recognition and respect.

Post a Comment