Is One’s Choice of Best Robin Generational?

Chris Sims of Comics Alliance (and, earlier, the Invincible Super-Blog) posted a very good essay this week on the questions: “Who is or was the best Robin? What is the Best Robin moment in Comic Book History?”

Chris Sims of Comics Alliance (and, earlier, the Invincible Super-Blog) posted a very good essay this week on the questions: “Who is or was the best Robin? What is the Best Robin moment in Comic Book History?”

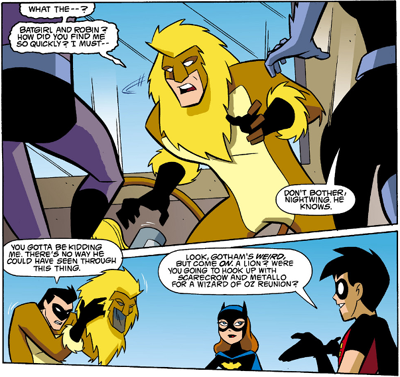

Ultimately Sims decides that what defines Robin is helping Batman, and by that measure he chooses Tim Drake as the best. That approach allows him to praise Dick Grayson for having been Robin and leaving that role to become a major character in the DC Universe. He also finds the best Robin moment when Carrie Kelly fully adopts the role, not through any feat of acrobatics or detection but simply in assuring Batman that he has help.

I see only one major flaw in the essay, and it’s part of Sims’s argument in favor of Tim Drake:

Tim's not in it for himself, and a lot of that comes from the simple fact that he doesn't need to be. When he first appears, he doesn't have a tragedy that defines his past and drives him to seek vengeance. In fact, he has the exact opposite: It's not really exaggerating to say that he's the single most privileged, well-adjusted character in the entire Batman mythos. He's rich enough to live more-or-less next door to Wayne Manor, he has two loving (and living) parents. The one thing that drives him is that he's a kid who loves Batman.But why does Tim (like Sims) love Batman? A big part of the reason, I think, is that he doesn’t have “two loving (and living) parents” with him anymore. When Tim first connects with Batman and puts on the Robin suit, his parents Jack and Janet have parked him at a boarding school while they travel the world doing business deals and sniping at each other. Tim’s interest in Dick Grayson isn’t fueled just by having met the young circus flyer on a bad night; he also hungers for a family. His interest in Batman isn’t just driven by justice; it’s also a desire for an admirable father in his life.

Soon after Tim starts interning in the bat-cave (though that was before the term “interning” had escaped the confines of the medical field), his mother is killed and his father paralyzed by a criminal in Haiti. DC Comics planned for Jack Drake to die soon as well, making Tim’s trajectory the same as the preceding Robins: orphaned by crime, taken in by Bruce Wayne. But scripter Chuck Dixon kept arguing (and demonstrating) that there was more drama in keeping the man alive.

Instead, for more than a decade Tim juggled life with his father and life with Batman, which set him apart from past Robins. And it’s tough to say which man caused Tim more trouble. Jack Drake fell in love with his physical therapist Dana and married her, moved the family out of Gotham and then back, sent Tim to another boarding school, lost all his money, found out about Tim’s double life, and so on. An underlying theme of the Robin comics then was that Tim was actually the more dependable and responsible of the Drakes, the one who was really looking after other people.

Instead, for more than a decade Tim juggled life with his father and life with Batman, which set him apart from past Robins. And it’s tough to say which man caused Tim more trouble. Jack Drake fell in love with his physical therapist Dana and married her, moved the family out of Gotham and then back, sent Tim to another boarding school, lost all his money, found out about Tim’s double life, and so on. An underlying theme of the Robin comics then was that Tim was actually the more dependable and responsible of the Drakes, the one who was really looking after other people.In other words, Tim still needed the strong father figure of Batman in his life, whether he could admit that or not. That’s why I don’t think Tim Drake became Robin just for justice. He also had private psychological needs compelling him to take on that role. (Another underlying theme, stronger in the 2000s, was that Tim was also often more mature than Bruce Wayne.)

I also suspect Chris Sims has a particular perspective on the Robins question based on his age—or more particularly on the age when he was reading superhero comics most avidly. Now I recognize that as a professional comics writer with a specialty in Batman he’s still reading superhero comics avidly, and that he’s consumed and considered the canon published back before he started. Nonetheless, I think that the stories one read as a child and young adolescent exert the strongest emotional tug and establish one’s expectations.

In another essay Sims has stated that he was twelve in 1994 when he started to collect back issues. In other words, he was at that crucial age when:

- Tim Drake was established as Robin. Furthermore, by then Tim had his father and stepmother at home (hence the “loving parents” understanding).

- Jason Todd was established as the dead Robin, the possibly homicidal Robin, the Robin that haunted Bruce Wayne. As I’ve written, this characterization didn’t solidify until after 1989.

- Dick Grayson was established as Nightwing, the former Robin, but the New Titans were past their glory days.

- Carrie Kelly was a possible future Robin who appeared in one revolutionary volume.

The Robin that came before—the first, red-haired Jason Todd—gets less than a sentence. Of the Robins that came later, Stephanie Brown is dismissed with a hand wave (“Stacy?”). Jason Todd’s return from the dead is treated as an unnecessary, unfortunate change that doesn’t affect his symbolic significance. Damian Wayne gets a longer analysis, and a good one, but it still seems clear that Sims’s heart is back in the 1990s.

Another essayist might conclude that Dick Grayson is the best Robin because he established the mold not just for that character but for all kid sidekicks in superhero comics; because he provided the emotion and humor that the first year of Batman stories lacked; because he was popular enough to appear on more DC covers of the 1940s than any other character; because his relationship with Bruce Wayne offered the only ongoing emotional depth in Batman comics for two decades; because he set the standard all subsequent sidekicks aspire to. And that reader probably read the comics of the 1940s and 1950s at a crucial age.

Yet another fan might argue that Dick is the best Robin because Batman could rely on him whether they were fighting gangsters or extraterrestrials; because he symbolized the best of America’s youth but would, both Alfred and Earth-2 agreed, grow up to be a crime-fighter; because he had no powers but was still the Teen Titans’ leader and badass; because as “Teen Wonder” he offered DC Comics a way to gingerly explore youth culture. And that reader probably read the comics of the 1960s and 1970s, and watched the ABC TV show, at a crucial age.

As I’ve written several times, my first prolonged exposure to superhero comics was the Batman: From the ’30s to the ’70s collection, which emphasized the stories between Robin’s arrival in 1940 and the “New Look” of 1964. And the last superhero comics I was reading in my late teens was the New Teen Titans series in which Dick Grayson made the leap to become Nightwing.

So for me that character wasn’t always a former Robin, and the goofy, shallow stories of the 1950s aren’t just quaint embarrassments—though they were juvenile adventures that Dick Grayson’s character helped lead the company away from as he matured in the early 1980s. Sims’s analysis is rooted in DC’s post-Crisis universe; my expectations were established before the Crisis struck.

For other readers, younger than both of us, Stephanie Brown’s brief period as Robin might loom much larger because it came at a crucial time in their own exploration of Batman comics, and Jason Todd might not be the dead Robin but the Robin who returned from the dead and is still not fully part of the family. Some such readers might prefer those other Robins, arguing that they had so few of Tim’s advantages (and so little of his support from the publisher and the fans he was clearly designed to reflect).

Even younger readers might have just had their expectations shaped by the presence of Damian Wayne for the past few years, seeing him as the best Robin (just as he’d want). Readers whose notions are being shaped by the “New 52” universe are also seeing quite a different Tim Drake, with a different family history and different challenges to overcome. So they may well come to a different conclusion about the best Robin.

I’m not saying that everyone of Sims’s comics-reading generation would agree with him while his arguments would fail on everyone else. I just think that his essay and its conclusions reflect the age when comics meant the most of him, and probably resonate most strongly with people of similar experiences.

Because my own experience starts before Dick Grayson was a former Robin, I’m inclined to see more of the essence of Robin in him, and to see Tim Drake as striving always to match that nearly Platonic model (which Dick might be the first to acknowledge he himself didn’t always attain).

But I’ve become very fond of the first Tim as well, and wouldn’t want to give up either character. As I wrote back here, I imagine Tim would agree that Dick was the best Robin and Dick would say Tim was.

But I’ve become very fond of the first Tim as well, and wouldn’t want to give up either character. As I wrote back here, I imagine Tim would agree that Dick was the best Robin and Dick would say Tim was.Of course, Sims might argue that Tim’s ability to win over a crotchety reader who grew up with Grayson is actually evidence that Tim deserves top honors.

(And the best Robin moment of all time? It’s in The Dark Knight Returns, to be sure. But it’s when Carrie is ready to hold off Superman with an effin’ slingshot.)