A Sidekick in the Pants

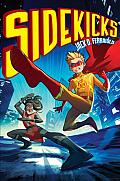

Sidekicks has a mighty “tween”-looking cover for a book that starts out with a boner.

In fact, teen-sidekick-getting-an-erection was the starting-point for novelist Jack D. Ferraiolo, as he explained on his blog:

Then came Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and more emphasis on realism/grittiness in superhero comics. In 2007, even DC addressed the erection question in Nightwing Annual, #2, which shows a late-teens Robin wishing for a longer cape and a minute to compose himself after getting too close to Batgirl.

Ferraiolo’s prose novel examines the plight of the adolescent sidekick through the voice of Bright Boy, ward of Phantom Justice. Their relationship is obviously modeled on that of Batman and Robin. As a dark-caped crimefighter, Phantom Justice says, “Good soldier”; he talks about “embracing the night” but can’t connect with anyone emotionally. There’s even an Alfred figure, a butler and voice of common sense.

However, in this world some people have been born with extra strength, speed, and/or intelligence. Phantom Justice and Bright Boy aren’t “badass normal” like Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson. They’re “plus-plus.” And while their world has mad scientists with amazing inventions, there’s no Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, or Spectre to keep them from the top of the pecking order.

Reviewers obviously new to the superhero genre seem struck by the drastic reversals built into the plot, but those are common in adventure comics. What seems fresh to me is the realistic dialogue between the two adolescents feeling their way into a complicated love affair. On the downside, there are pages and pages of exposition.

I thought the biggest flaw in Sidekicks is that it ends with no “price of fantasy,” as Ellen Howard has termed it. At the start of the book, protagonist Scott feels like a nobody in high school and an embarrassment in the media—those are the costs of being a superpowered hero. (In addition, Scott’s parents died in an accident when he was little, but—unlike the ache that drives the Harry Potter books, even though Harry never knew his parents—we don’t feel that loss.)

At the end of Sidekicks [and that means SPOILERS AHEAD], Scott has solved the problems that bothered him at the start. He’s got a girlfriend, and pals, and cooler clothes, and public adultation, and freakin’ superpowers. For a while it looks like he has to pay a big price—he thinks two of the people he loves have died. But everyone turns out okay in various futuristic ways. The only person he really loses is someone whom he could never warm up to. Scott even manages to come out on top of the Oedipal conflict. It’s total wish-fulfillment with very little cost. [End of SPOILERS] But, as with the plot reversals, that probably won’t look like a flaw to teen readers not yet jaded about this genre.

Which brings me back to that cover. Amulet designer Chad Beckerman has shown how it went through a lot of changes, starting with a more realistic close-up of the main character (wearing braces, though I don’t think they’re mentioned in the book) before ultimately ending up with the art above. One intermediate version appears to the left. Twice, Beckerman writes, the design sketches had “too much crotch.” Yet “too much crotch” is exactly where the story starts.

Ferraiolo writes that he’s heard some criticism (from adults) and lost some library speaking gigs because people thought the novel was inappropriate for younger readers. I think the story’s quite appropriate for young adolescents. But the final cover’s cartoony art, and our culture’s assumption that all superhero stories are appropriate for kids, may suggest to some adults that this is a book for the middle grades.

In fact, teen-sidekick-getting-an-erection was the starting-point for novelist Jack D. Ferraiolo, as he explained on his blog:

I was a full-fledged Batman freak... and being that this was the early eighties (and the Batman comics from the 70s were still pretty available), the DC writers/artists were continuing the process of aging Robin up. I remember…looking at a comic of a late teen/early 20’s Robin and thinking, “Man, he should really cover up.” Here he is fighting hardened criminals – thugs, thieves, murderers – and he's wearing the tiniest pair of green jockey shorts imaginable. And no one mentions it? I mean, not one street tough has something to say about Robin’s itty-bitty bikini bottoms? Especially with all those high kicks he was throwing around?Actually, Robin’s friends had been calling him “Shortpants” for years by then. Marv Wolfman and George Pérez acknowledged the oddity of an eighteen-year-old in trunks as they discussed the early New Teen Titans. Mention of Dick Grayson’s bare legs was forbidden only for villains and, of course, Bruce Wayne.

Then came Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and more emphasis on realism/grittiness in superhero comics. In 2007, even DC addressed the erection question in Nightwing Annual, #2, which shows a late-teens Robin wishing for a longer cape and a minute to compose himself after getting too close to Batgirl.

Ferraiolo’s prose novel examines the plight of the adolescent sidekick through the voice of Bright Boy, ward of Phantom Justice. Their relationship is obviously modeled on that of Batman and Robin. As a dark-caped crimefighter, Phantom Justice says, “Good soldier”; he talks about “embracing the night” but can’t connect with anyone emotionally. There’s even an Alfred figure, a butler and voice of common sense.

However, in this world some people have been born with extra strength, speed, and/or intelligence. Phantom Justice and Bright Boy aren’t “badass normal” like Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson. They’re “plus-plus.” And while their world has mad scientists with amazing inventions, there’s no Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, or Spectre to keep them from the top of the pecking order.

Reviewers obviously new to the superhero genre seem struck by the drastic reversals built into the plot, but those are common in adventure comics. What seems fresh to me is the realistic dialogue between the two adolescents feeling their way into a complicated love affair. On the downside, there are pages and pages of exposition.

I thought the biggest flaw in Sidekicks is that it ends with no “price of fantasy,” as Ellen Howard has termed it. At the start of the book, protagonist Scott feels like a nobody in high school and an embarrassment in the media—those are the costs of being a superpowered hero. (In addition, Scott’s parents died in an accident when he was little, but—unlike the ache that drives the Harry Potter books, even though Harry never knew his parents—we don’t feel that loss.)

At the end of Sidekicks [and that means SPOILERS AHEAD], Scott has solved the problems that bothered him at the start. He’s got a girlfriend, and pals, and cooler clothes, and public adultation, and freakin’ superpowers. For a while it looks like he has to pay a big price—he thinks two of the people he loves have died. But everyone turns out okay in various futuristic ways. The only person he really loses is someone whom he could never warm up to. Scott even manages to come out on top of the Oedipal conflict. It’s total wish-fulfillment with very little cost. [End of SPOILERS] But, as with the plot reversals, that probably won’t look like a flaw to teen readers not yet jaded about this genre.

Which brings me back to that cover. Amulet designer Chad Beckerman has shown how it went through a lot of changes, starting with a more realistic close-up of the main character (wearing braces, though I don’t think they’re mentioned in the book) before ultimately ending up with the art above. One intermediate version appears to the left. Twice, Beckerman writes, the design sketches had “too much crotch.” Yet “too much crotch” is exactly where the story starts.

Ferraiolo writes that he’s heard some criticism (from adults) and lost some library speaking gigs because people thought the novel was inappropriate for younger readers. I think the story’s quite appropriate for young adolescents. But the final cover’s cartoony art, and our culture’s assumption that all superhero stories are appropriate for kids, may suggest to some adults that this is a book for the middle grades.

No comments:

Post a Comment