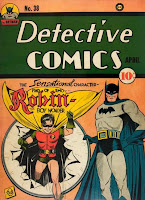

A Full Look at Detective Comics, #38

Comixology’s Nightwing 101 sale (ending this evening) offered me a 99¢ look at the whole of Detective Comics, #38, the magazine which introduced Robin as the Sensational Character Find of 1940.

As I’ve written previously, this was Whitney Ellsworth’s first issue as chief editor, and he replaced the story originally slated for this issue with Robin’s debut. Within a short time, Ellsworth instituted new rules about guns and killing in Batman tales.

But the Batman cover feature was only the first of several stories in that issue of Detective. At twelve pages it was the longest, but the whole magazine contained 58 pages of comics and a couple of prose items (not included in the Comixology download).

The other graphic features were episodes of “Spy” and “Slam Bradley,” both written by Jerry Siegel; “Red Logan,” an American reporter in London; “The Crimson Avenger,” a Green Hornet knock-off; “Cliff Crosby,” a “Terry and the Pirates” knock-off; “Speed Saunders, Ace Investigator”; and “Steve Malone, District Attorney.” The Crimson Avenger had preceded Batman as a masked hero, but the rest of the magazine’s heroes were square-jawed young white men in suits. (Well, Cliff Crosby wears flying gear and spends an unusual amount of time shirtless at the North Pole.)

Aside from Dick Grayson and the newsboys he encounters, the magazine shows only two recognizable children: a girl and “crippled boy” whom Slam Bradley and his grotesque sidekick rescue from a fire. Within a year, boy sidekicks and heroes would proliferate as the success of Captain Marvel and Robin sent the industry chasing after its main readership. Cliff Crosby was soon dubbed “Young America’s Hero” rather than “Famous Explorer.”

Another striking aspect of the magazine is that the Batman and Robin story is much better than the rest. Granted, scripter Bill Finger had more pages to work with, but a lot of the other tales make little sense, relying on coincidences, leaps of logic, and ludicrous action sequences.

Another striking aspect of the magazine is that the Batman and Robin story is much better than the rest. Granted, scripter Bill Finger had more pages to work with, but a lot of the other tales make little sense, relying on coincidences, leaps of logic, and ludicrous action sequences.

In contrast, Batman and Robin’s drive to shut down Boss Zucco’s protection racket proceeds rationally, building to a night-time battle on the skeleton of an unfinished building. For that fight Jerry Robinson designed pages of dark panels alternating with light, full moon in the background.

Bob Kane and Robinson’s draftsmanship wasn’t as good as that of some other artists in this early comic, but their composition was much better. Only Jack Lehti’s work on the Crimson Avenger finds as much depth and variety in the panels. (Kane and his crew were working with a varied three-tier page structure. Fred Guardineer used a more uniform three tiers in “Speed Saunders,” and all the other stories are told in four tiers, like Kane’s original, six-page Batman tale.)

The coloring on most pages is awful. There was a limited palette, and the colorists deployed it poorly. One page of “Speed Saunders” shows three different women in red tops and green skirts, making it easy to confuse them; on another, two planes keep switching colors. In “Cliff Crosby,” the polar bears are brown. And this is supposed to be an English village landscape at night from “Red Logan.”

With that baseline, Robin’s costume of red, green, and yellow doesn’t seem so unusual.

As I’ve written previously, this was Whitney Ellsworth’s first issue as chief editor, and he replaced the story originally slated for this issue with Robin’s debut. Within a short time, Ellsworth instituted new rules about guns and killing in Batman tales.

But the Batman cover feature was only the first of several stories in that issue of Detective. At twelve pages it was the longest, but the whole magazine contained 58 pages of comics and a couple of prose items (not included in the Comixology download).

The other graphic features were episodes of “Spy” and “Slam Bradley,” both written by Jerry Siegel; “Red Logan,” an American reporter in London; “The Crimson Avenger,” a Green Hornet knock-off; “Cliff Crosby,” a “Terry and the Pirates” knock-off; “Speed Saunders, Ace Investigator”; and “Steve Malone, District Attorney.” The Crimson Avenger had preceded Batman as a masked hero, but the rest of the magazine’s heroes were square-jawed young white men in suits. (Well, Cliff Crosby wears flying gear and spends an unusual amount of time shirtless at the North Pole.)

Aside from Dick Grayson and the newsboys he encounters, the magazine shows only two recognizable children: a girl and “crippled boy” whom Slam Bradley and his grotesque sidekick rescue from a fire. Within a year, boy sidekicks and heroes would proliferate as the success of Captain Marvel and Robin sent the industry chasing after its main readership. Cliff Crosby was soon dubbed “Young America’s Hero” rather than “Famous Explorer.”

Another striking aspect of the magazine is that the Batman and Robin story is much better than the rest. Granted, scripter Bill Finger had more pages to work with, but a lot of the other tales make little sense, relying on coincidences, leaps of logic, and ludicrous action sequences.

Another striking aspect of the magazine is that the Batman and Robin story is much better than the rest. Granted, scripter Bill Finger had more pages to work with, but a lot of the other tales make little sense, relying on coincidences, leaps of logic, and ludicrous action sequences.In contrast, Batman and Robin’s drive to shut down Boss Zucco’s protection racket proceeds rationally, building to a night-time battle on the skeleton of an unfinished building. For that fight Jerry Robinson designed pages of dark panels alternating with light, full moon in the background.

Bob Kane and Robinson’s draftsmanship wasn’t as good as that of some other artists in this early comic, but their composition was much better. Only Jack Lehti’s work on the Crimson Avenger finds as much depth and variety in the panels. (Kane and his crew were working with a varied three-tier page structure. Fred Guardineer used a more uniform three tiers in “Speed Saunders,” and all the other stories are told in four tiers, like Kane’s original, six-page Batman tale.)

The coloring on most pages is awful. There was a limited palette, and the colorists deployed it poorly. One page of “Speed Saunders” shows three different women in red tops and green skirts, making it easy to confuse them; on another, two planes keep switching colors. In “Cliff Crosby,” the polar bears are brown. And this is supposed to be an English village landscape at night from “Red Logan.”

With that baseline, Robin’s costume of red, green, and yellow doesn’t seem so unusual.

No comments:

Post a Comment