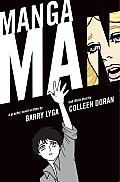

Making Sense of Manga Man

Manga Man, written by Barry Lyga and illustrated by Colleen Doran, explores the premise of a typical manga hero coming to earth in an American high school.

Of course, there is no “typical manga hero.” Ryoko Kiyama is a typical “bishonen” or “beautiful boy” type from one genre of Japanese comics. He’s an adolescent with big eyes and extraordinary hair. He has a tendency to express emotions by turning into a cute, small chibi version of himself. Given his background, Ryoko is comfortable with barely explained gender-shifting, robot attacks, and sitting still to watch nature for several panels.

For Marissa Montaigne, the prettiest girl in her high school, Ryoko is a delightful change from her ex-boyfriend the football captain, but their attraction doesn’t go any deeper than that.

Artist Colleen Doran does a fine job of fitting characters in both styles into the same panels. Scripter Barry Lyga also seems to focus on that contrast rather than on the characters’ relationship, and I didn’t think all his ideas panned out.

For example, because Japanese comics are read right to left, a couple of times Ryoko finds himself moving opposite to his American classmates. He can even foresee the future in a limited, one-panel way. I kept waiting for that to become a major part of the plot, but it didn’t.

At another point, Ryoko reveals his ability to move into the gutters between panels, and thus to move supernaturally between scenes, again emphasizing his identity as a comics character. But then he shows his love interest, Marissa Montaigne, how to do this as well, meaning that she’s also living in a comics universe.

For me that shifts Manga Man from being about a comics character visiting the real world to a Japanese comics character visiting some form of American comics—but not one matching the conventions of any genre I know. And the American characters just weren’t developed enough to stand on their own without a genre background.

Then the reality shifts back again as Ryoko gets in trouble for fighting too rough with his romantic rival. He expects to cause no more damage than in his typical stories, but Marissa’s old boyfriend ends up on a ventilator. Which left me further confused since a long-standing complaint about American comics is that they show unrealistic violence without consequences.

Of course, there is no “typical manga hero.” Ryoko Kiyama is a typical “bishonen” or “beautiful boy” type from one genre of Japanese comics. He’s an adolescent with big eyes and extraordinary hair. He has a tendency to express emotions by turning into a cute, small chibi version of himself. Given his background, Ryoko is comfortable with barely explained gender-shifting, robot attacks, and sitting still to watch nature for several panels.

For Marissa Montaigne, the prettiest girl in her high school, Ryoko is a delightful change from her ex-boyfriend the football captain, but their attraction doesn’t go any deeper than that.

Artist Colleen Doran does a fine job of fitting characters in both styles into the same panels. Scripter Barry Lyga also seems to focus on that contrast rather than on the characters’ relationship, and I didn’t think all his ideas panned out.

For example, because Japanese comics are read right to left, a couple of times Ryoko finds himself moving opposite to his American classmates. He can even foresee the future in a limited, one-panel way. I kept waiting for that to become a major part of the plot, but it didn’t.

At another point, Ryoko reveals his ability to move into the gutters between panels, and thus to move supernaturally between scenes, again emphasizing his identity as a comics character. But then he shows his love interest, Marissa Montaigne, how to do this as well, meaning that she’s also living in a comics universe.

For me that shifts Manga Man from being about a comics character visiting the real world to a Japanese comics character visiting some form of American comics—but not one matching the conventions of any genre I know. And the American characters just weren’t developed enough to stand on their own without a genre background.

Then the reality shifts back again as Ryoko gets in trouble for fighting too rough with his romantic rival. He expects to cause no more damage than in his typical stories, but Marissa’s old boyfriend ends up on a ventilator. Which left me further confused since a long-standing complaint about American comics is that they show unrealistic violence without consequences.

No comments:

Post a Comment