A Wizard of Oz by Way of New Delhi

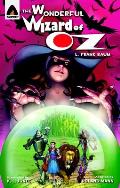

Last week I picked up a copy of the Campfire Classics graphic adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz. This is one of a long list of public-domain stories brought to the US by Steerforth of New Hampshire and distributed by Random House.

Roland Mann, a veteran of Malibu Comics, is credited as “wordsmith.” Kevin (or K. L.) Jones is the credited “penciler.” All of the other names on the credits page are Indian.

[Comics publishers often print long lists of credits on a copyright page, including company executives with minimal involvement in that title. In contrast, a traditional children’s book usually doesn’t state its editor’s name anywhere. This is another of the curious cultural differences between the two industries.]

Campfire Classics are produced out of New Delhi. Back in 2010, Publishing Perspectives reported: “Among the advantages the company has is the ability to keep most of the work in-house. The company employs a bullpen of 20 full-time artists on staff to do with drawing and coloring.” As a result, a 76-page full-color Campfire book can retail for $9.99.

According to Mann, for the Classics series ”The goal is to stick very close to the original and get young readers visually interested in the work so that they might actually seek the original out.”

For him, that assignment meant reading The Wonderful Wizard of Oz for the first time. His blog shows how he discovered the obvious big differences between the book and the famous MGM movie.

Still, that movie exerted a heavy influence on the visuals of this adaptation. Jones and the bullpen depict Dorothy as an adolescent with brown braids; for much of the book she wears a blue-and-white checked dress. (In the Emerald City she changes into one of the least flattering dresses I’ve ever seen, shown here.)

The Wicked Witch of the West has the green skin and long fingernails that Margaret Hamilton wore in the 1939 movie, but (aside from the scars over her missing eye) has a young and attractive face—a sign of Wicked’s influence.

Campfire is aiming for the American and British markets, to judge by the titles and topics in its catalogue. I rather hoped to find details that struck me as a markedly Indian interpretation of the legend, but didn’t spot any. The biggest departure from the traditional range of Wizard of Oz characterizations is, as this picture shows, the Winkies as little yellow goblins. The lettering is unimaginative, possibly designed to stick as closely as possible to what readers might find in prose books.

As the publisher requested, Mann’s script sticks close to the source material. It includes the Winged Monkeys’ flashback and the visit to the China Country, two episodes that adapters often leave out. It skips only the visit to the family just outside the Emerald City, which offers characterization but not much action.

Indeed, Mann clearly concentrates his limited space on action scenes. The travelers’ confrontation with the Kalidahs takes nearly three pages. There’s a spread and more on Nick Chopper’s transformation into the Tin Woodman through multiple axe accidents, starting with the picture of young Nick at the right.

In contrast, the Wizard gives out brains, a heart, and courage in only three panels covering half a page. Those moments help to define the thematic core of the novel, but the script zips us through them. Similarly, there’s little pause for Dorothy’s sorrow after the Wizard’s balloon flies away.

As a result, I enjoyed moments of this adaptation, and found some of the creators’ other choices interesting to contemplate, but I didn’t think the overall storytelling was emotionally involving or fully successful.

One of Jones’s upcoming titles for Campfire is a comics biography of Abraham Lincoln. Mann, in contrast, is a neo-Confederate, so I don’t think he’ll be working on that one.

Roland Mann, a veteran of Malibu Comics, is credited as “wordsmith.” Kevin (or K. L.) Jones is the credited “penciler.” All of the other names on the credits page are Indian.

[Comics publishers often print long lists of credits on a copyright page, including company executives with minimal involvement in that title. In contrast, a traditional children’s book usually doesn’t state its editor’s name anywhere. This is another of the curious cultural differences between the two industries.]

Campfire Classics are produced out of New Delhi. Back in 2010, Publishing Perspectives reported: “Among the advantages the company has is the ability to keep most of the work in-house. The company employs a bullpen of 20 full-time artists on staff to do with drawing and coloring.” As a result, a 76-page full-color Campfire book can retail for $9.99.

According to Mann, for the Classics series ”The goal is to stick very close to the original and get young readers visually interested in the work so that they might actually seek the original out.”

For him, that assignment meant reading The Wonderful Wizard of Oz for the first time. His blog shows how he discovered the obvious big differences between the book and the famous MGM movie.

Still, that movie exerted a heavy influence on the visuals of this adaptation. Jones and the bullpen depict Dorothy as an adolescent with brown braids; for much of the book she wears a blue-and-white checked dress. (In the Emerald City she changes into one of the least flattering dresses I’ve ever seen, shown here.)

The Wicked Witch of the West has the green skin and long fingernails that Margaret Hamilton wore in the 1939 movie, but (aside from the scars over her missing eye) has a young and attractive face—a sign of Wicked’s influence.

Campfire is aiming for the American and British markets, to judge by the titles and topics in its catalogue. I rather hoped to find details that struck me as a markedly Indian interpretation of the legend, but didn’t spot any. The biggest departure from the traditional range of Wizard of Oz characterizations is, as this picture shows, the Winkies as little yellow goblins. The lettering is unimaginative, possibly designed to stick as closely as possible to what readers might find in prose books.

As the publisher requested, Mann’s script sticks close to the source material. It includes the Winged Monkeys’ flashback and the visit to the China Country, two episodes that adapters often leave out. It skips only the visit to the family just outside the Emerald City, which offers characterization but not much action.

Indeed, Mann clearly concentrates his limited space on action scenes. The travelers’ confrontation with the Kalidahs takes nearly three pages. There’s a spread and more on Nick Chopper’s transformation into the Tin Woodman through multiple axe accidents, starting with the picture of young Nick at the right.

In contrast, the Wizard gives out brains, a heart, and courage in only three panels covering half a page. Those moments help to define the thematic core of the novel, but the script zips us through them. Similarly, there’s little pause for Dorothy’s sorrow after the Wizard’s balloon flies away.

As a result, I enjoyed moments of this adaptation, and found some of the creators’ other choices interesting to contemplate, but I didn’t think the overall storytelling was emotionally involving or fully successful.

One of Jones’s upcoming titles for Campfire is a comics biography of Abraham Lincoln. Mann, in contrast, is a neo-Confederate, so I don’t think he’ll be working on that one.

1 comment:

I just found this--great write up. And on my birthday, even!

No, I didn't get to work on that Old Abe book...but I DID get to do Twain's Huck Finn, and that was a lot of fun!

Thanks for write up! I appreciate your opinion.

-Roland

Post a Comment