Thought Balloons and Systems of Narration

Thought balloons (discussed at length yesterday) were part of a system of narration that dominated American adventure comics for decades. This system also involved an omniscient narrator, often bombastic and occasionally redundant.

Thought balloons (discussed at length yesterday) were part of a system of narration that dominated American adventure comics for decades. This system also involved an omniscient narrator, often bombastic and occasionally redundant.

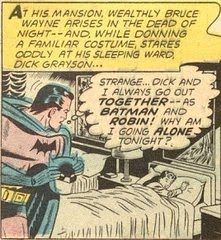

Using thought balloons, this narrative approach could reveal any character’s thoughts, including hero or villain, as long as it served the story. Conversely, since adventure comics depended on sudden plot turns, this style also involved concealing characters’ thoughts if they would give away the next twist too early. (See “Reason for Robin, #2.”)

Other comics genres took different approaches to narration. Romance comics were often told in the first-person voice of the central character, like magazine “confessions”; both captions and thought balloons let us into that character’s head, and hers alone. Horror comics were introduced and narrated by recurring figures like the Crypt Keeper, who had supernatural insight into characters’ thoughts and fates. And of course there were experiments and exceptions within every genre. To find examples of the typical adventure-comics approach in full flower, I looked at Batman issues from the early 1980s, since they were handy. Batman, #336, has a script by Roy Thomas, based on a Bob Rozakis plot. The captions are in the voice of an omniscient narrator. There are thought balloons from Batman/Bruce Wayne, Alfred Pennyworth, Commissioner Jim Gordon, and two villains, the Spellbinder and the Cluemaster. That narrator knows everything!

To find examples of the typical adventure-comics approach in full flower, I looked at Batman issues from the early 1980s, since they were handy. Batman, #336, has a script by Roy Thomas, based on a Bob Rozakis plot. The captions are in the voice of an omniscient narrator. There are thought balloons from Batman/Bruce Wayne, Alfred Pennyworth, Commissioner Jim Gordon, and two villains, the Spellbinder and the Cluemaster. That narrator knows everything!

This style offers leeway for a character to take over the narration for a while. Gerry Conway’s main story in Batman, #338, has an omniscient narrator, also displays the hero’s voice in both thought balloons and captions, and quotes the villain’s voice in captions for a flashback. The captions in characters’ voices include quotation marks around the words. (This tale also has one passing thought balloon for a saleswoman we never see again.) Yet that same stretch of Batman magazine offers an alternative way of narrating adventure comics, a way that would come to dominate the form. That style appears in the back-up feature in Batman, #337-9, featuring none other than Robin.

Yet that same stretch of Batman magazine offers an alternative way of narrating adventure comics, a way that would come to dominate the form. That style appears in the back-up feature in Batman, #337-9, featuring none other than Robin.

Written by Conway, this three-part story shows Dick Grayson looking back on his life, exploring his roots in a traveling circus, and solidifying his identity beyond being Batman’s sidekick.

That story is narrated by Dick himself. The captions are all in his voice; there are no quotation marks to set them off from an omniscient narrator‘s captions.

Likewise, Dick is the only character trailing thought balloons. As narrator, he’s not privy to other characters’ thoughts, only to their actions and words. And as the following panel shows, the captions and thought balloons run into each other. (One theme of this installment is that Dick’s fretting about his past can distract him from the present.)  This first-person narrative approach makes perfect sense for this story. The external plot—a murder mystery at the circus—is minor. So minor that Dick appears in his Robin costume in only three panels of the third installment, all flashbacks.

This first-person narrative approach makes perfect sense for this story. The external plot—a murder mystery at the circus—is minor. So minor that Dick appears in his Robin costume in only three panels of the third installment, all flashbacks.

What matters in this tale is Dick’s internal journey to figuring out who he is, separate from Batman, with a different drive. That continues a process which began in preceding issues of Batman and which we also saw in concurrent issues of The New Teen Titans. And it was a forerunner of recent decades of superhero stories that are, at least nominally, as much about the heroes’ individual emotional lives as about their ability to catch bad guys and hit them. TOMORROW: Along the thought balloon trail.

TOMORROW: Along the thought balloon trail.

NEXT WEEK: Gerry Conway on Robin.

No comments:

Post a Comment