Titans Killed in Implosion?

Yesterday I wrote about my memories of New England’s infamous “Blizzard of ’78.” I wasn’t yet reading comic books then, but I’ve since learned that that meteorological event had a major effect on DC Comics.

Yesterday I wrote about my memories of New England’s infamous “Blizzard of ’78.” I wasn’t yet reading comic books then, but I’ve since learned that that meteorological event had a major effect on DC Comics.

In the mid-1970s DC was losing ground in the marketplace. Marvel’s comic books were hipper, attracting more college kids and fewer elementary-school kids. Even with constant turnover in the editor-in-chief's office, Marvel kept growing. So Warner Bros., which had become DC's parent company, fired editorial director Carmine Infantino and hired young Jenette Kahn, founder of Kids and Dynamite! magazines.

Kahn responded to economic pressures by raising prices—to fifty cents!—while also expanding the magazines. Issues grew from 17 pages to 25, meaning there were longer stories or backup stories. The company also put out “giant-sized” magazines for a whole dollar. Kahn sought to build more links between DC's magazines and kids' TV shows and movies.

DC and Marvel were then in a “newsstand war,” vying for space at news racks, drugstores, and other traditional retail outlets. Kahn’s strategy was a plethora of new titles to increase visibility, promoted to readers as the “DC Explosion.” Kirk Kimball’s Dial B for Blog website ran over the stats:

DC launched 16 new titles in 1975, 21 in 1976, 12 in 1977, and 8 in 1978—a total of 57 new titles in four years. New superhero books included Firestorm, Black Lightning, Shade the Changing Man, and Steel. There were also relaunches of older books such as Jack Kirby's New Gods and Mister Miracle.And among the relaunched books was The Teen Titans.

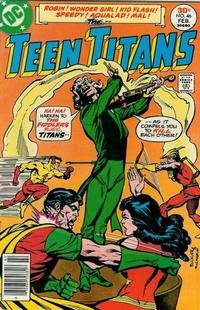

That title, featuring a team of superhero sidekicks led by Robin, had started in 1966, with scripts by Bob Haney. (His attempts at teen-aged slang are unintentionally their most entertaining feature.) That series ended with a whimper in 1973. But it began again with issue #44 in late 1976 under new scripter Bob Rozakis, who'd started as a prominent comics fan and broken into the business by supplying puzzles on superhero themes.

That title, featuring a team of superhero sidekicks led by Robin, had started in 1966, with scripts by Bob Haney. (His attempts at teen-aged slang are unintentionally their most entertaining feature.) That series ended with a whimper in 1973. But it began again with issue #44 in late 1976 under new scripter Bob Rozakis, who'd started as a prominent comics fan and broken into the business by supplying puzzles on superhero themes.Then came a force stronger than Wonder Girl. Here's more from Dial B:

In late 1977, America was frozen stiff as horrendous winter weather swept much of the nation, with one blizzard raging on for as long as 25 hours, and wind chills reaching 60 below zero. Seven western New York counties were declared national disaster areas, and in Buffalo, 29 people died of exposure. Then, in February 1978, the "Blizzard of 1978” battered the entire East Coast, claiming 54 lives and causing an estimated billion dollars in damage.DC's distribution system was crippled. And each of its magazines had a date right on the cover, meaning that they looked like old goods even before they got out of the warehouses.

The sales numbers looked awful, and Warner Bros. insisted that DC cut its line back. That required canceling sixty-five titles, a move that insiders sardonically called "the DC Implosion." Basically, the corporation threw in the towel and chose to focus on milking its core legacy properties, like Superman and Batman, rather than creating new characters. Marvel had won.

But here’s the thing. The last issue of Rozakis’s run was #53, with a cover date of February 1978. That means it was supposed to reach newsstands a month or two earlier, and he’d scripted it a month or two before that. DC must have called off the Teen Titans even before the winter of 1977-78 began. As Dial B’s stats show, the company was still introducing new titles in 1978, and didn’t cut back until late that year.

So why did DC kill the title? According to Cadigan’s Titans Companion interview with comics editor Len Wein, Kahn told him, “it was making a profit when we cancelled it, one of the few occasions in history that we cancelled a successful book because we were so embarrassed by the creative content.” Ooh.

I suspect that Rozakis, looking back after twenty years, amalgamated his memory of the Teen Titans cancellation with the “DC Implosion” that followed several months later. It's also possible that DC insiders' understanding of the “Implosion,” the basis of the description above, might be too simplistic; the real problem might have been lots of mediocre comics that were shut down gradually, but people preferred to blame it all on the weather.

Ironically, the Teen Titans cancellation and DC Implosion set up the company for three major developments of the next decade. First, the summer of 1978 brought the first Superman movie starring Christopher Reeve, a huge hit for Warner Bros. That made the corporation very happy about its DC Comics line, and bolstered Kahn’s strategy of tying comics to other media.

Second, Wein, Marv Wolfman, and George Pérez had a clear playing-field when they came up with The New Teen Titans in 1980. That series’ combination of gorgeous art and relatively mature, emotional stories made the sidekicks team into DC’s best and best-selling comic book of the new decade.

Second, Wein, Marv Wolfman, and George Pérez had a clear playing-field when they came up with The New Teen Titans in 1980. That series’ combination of gorgeous art and relatively mature, emotional stories made the sidekicks team into DC’s best and best-selling comic book of the new decade.And third, the market for comics moved away from those newsstands and drugstores into specialized comics shops, where the staff and clientele sought out quality. The New Teen Titans were one of the first new hits in that marketplace. With an eye on the new playing field, in the early 1980s Kahn and her editors took the bold step of going to Britain to recruit talented writers and artists. They brought back contracts with Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, and many others, part of a true explosion in American comics.

Bruce Wayne, secretly the

Bruce Wayne, secretly the  In addition, on rare occasions--three in the 1940s "Golden Age" of superhero comics, according to the sharp-eyed subscribers to

In addition, on rare occasions--three in the 1940s "Golden Age" of superhero comics, according to the sharp-eyed subscribers to  Reportedly that newspaper strip was written for a wider audience than the comics magazines. It was intended to entertain adults as well as kids. So what adult middle-America wanted in the mid-1940s, it seems, was the hilarity of a teenager in drag.

Reportedly that newspaper strip was written for a wider audience than the comics magazines. It was intended to entertain adults as well as kids. So what adult middle-America wanted in the mid-1940s, it seems, was the hilarity of a teenager in drag. The chest-beating insistence that dressing as a female is an awful fate seems so imperative that it resurfaces in the one time Tim Drake, the current Robin, has dressed as a young woman. As printed in the collection

The chest-beating insistence that dressing as a female is an awful fate seems so imperative that it resurfaces in the one time Tim Drake, the current Robin, has dressed as a young woman. As printed in the collection

My last

My last  Dick Grayson was a child worker from the beginning, as a star in his family's trapeze act. But he also took jobs after he went to live with millionaire Bruce Wayne.

Dick Grayson was a child worker from the beginning, as a star in his family's trapeze act. But he also took jobs after he went to live with millionaire Bruce Wayne. Sometimes Dick wore a work uniform as a disguise. For poorer jobs, a member of the

Sometimes Dick wore a work uniform as a disguise. For poorer jobs, a member of the  These days, a boy in his mid-teens would probably attract attention in most workplaces rather than deflect it. But Dick's ability to go undercover made more sense in the 1940s, when the character was created. Far more teen-aged boys were then at work in offices, stores, and workshops.

These days, a boy in his mid-teens would probably attract attention in most workplaces rather than deflect it. But Dick's ability to go undercover made more sense in the 1940s, when the character was created. Far more teen-aged boys were then at work in offices, stores, and workshops. Other examples of youthful work in that first generation of comic-book creators:

Other examples of youthful work in that first generation of comic-book creators: This trend didn't completely die off, either. DC Comics's current president, Paul Levitz, took his first job at the company at age sixteen,

This trend didn't completely die off, either. DC Comics's current president, Paul Levitz, took his first job at the company at age sixteen,