Hobbesian Philosophizing

From Philip Sandifer's "When Real Things Happen to Imaginary Tigers," in InterText:Let us begin more simply – with a straightforward observation about Calvin and Hobbes. The observation is this: Hobbes is imaginary.

Why wasn't anyone around to tell me this in 1985?

Actually, I found this essay straining alternately to say too little and too much. Setting aside the lit-crit language, it aims to illuminate our expectation in reading Calvin and Hobbes: that each morning we'd find a small joke that could be part of a small weekly story but wouldn't greatly change the characters and situation, so that the next morning we could have the same experience; but, ironically, that the characters and situation portrayed would have a fluid relationship with the physical and biological world.

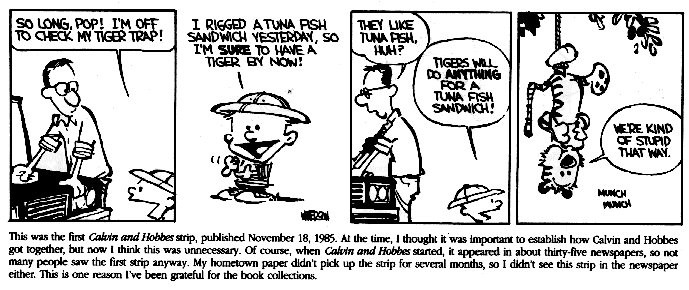

When Bill Watterson started Calvin and Hobbes, focused on two supporting characters from another proposed strip, he offered an "origin" story that creates a beginning to the strip's reality: However, as Watterson later noted, that first strip ran in so few newspapers that hardly any readers saw it in "real time." Almost all of us came to Calvin and Hobbes while the story was already going on. And we didn't mind because we're used to figuring out most comic strips that way.

However, as Watterson later noted, that first strip ran in so few newspapers that hardly any readers saw it in "real time." Almost all of us came to Calvin and Hobbes while the story was already going on. And we didn't mind because we're used to figuring out most comic strips that way.

Sandifer's essay briefly acknowledges another model of comic strip in which characters age and change over time: Gasoline Alley, Doonesbury, and Jump Start, for instance. And that's not even getting into other forms of comics, such as monthly magazines and standalone graphic novels.

I think it might be more illuminating to consider how such different types of strips portray time and space. As it is, an essay on Calvin and Hobbes must conclude with little more insight than:

As for reading too much, Sandifer's argument puts great emphasis on a character who appeared for one week: In fact, the reader is often expected to specifically forget things – for example, the character of Uncle Max, who Watterson admits was a mistake to introduce, and of whom he says simply "Max is gone" (Watterson, Tenth 76). This is telling – the audience is expected to forget Uncle Max. He is gone – not a part of the strip.

Twice Sandifer insists we readers are supposed to "forget" Uncle Max. But Watterson never insisted on that. He simply wrote in an anthology:After the story ran, I realized that I hadn't established much identity for Max, and that he didn't bring out anything new in Calvin. The character, I concluded, was redundant. It was also very awkward that Max could not address Calvin's parents by name, and this should have tipped me off that the strip was not designed for the parents to have outside adult relationships. Max is gone.

Max never appeared again in Calvin's house or in the strip, but we readers didn't have to wrote Max out of out memories. That week of strips kept being reprinted. Just as Calvin mentions grandparents who are never seen, so Uncle Max remained available off-stage if Watterson ever found a use for him. In the meantime, there was a new strip each morning, so we never had reason to miss him. And that's all we asked for.

No comments:

Post a Comment