I’m sure the Chicago Manual of Style has rules on how to render the title of a novel in a series, but I’m not bothering to look them up. What I’m calling Beka Cooper: Terrier, by Tamora Pierce, is the first in a new series named after its heroine, a young woman named Beka Cooper. I suspect each volume will show her at one stage in her law-enforcement career. In this one she’s a trainee (“Puppy”) who proves herself a dogged “Terrier.” Sort of like Cherry Ames, Rookie Cop.

I’m sure the Chicago Manual of Style has rules on how to render the title of a novel in a series, but I’m not bothering to look them up. What I’m calling Beka Cooper: Terrier, by Tamora Pierce, is the first in a new series named after its heroine, a young woman named Beka Cooper. I suspect each volume will show her at one stage in her law-enforcement career. In this one she’s a trainee (“Puppy”) who proves herself a dogged “Terrier.” Sort of like Cherry Ames, Rookie Cop.

The book takes place in Pierce’s Tortall realm centuries before the action of her first novel, Alanna. The card page (“Other Books By...”) lists three other Tortall quartets and a twosome. So while I hadn’t read any of Pierce’s books before, it wasn’t for lack of effort on her part.

Beka Cooper: Terrier is a police procedural and coming-of-age story set in a fairly “high” fantasy world (no dragons, but mages, knights, etc.). It’s not a mystery, really. Beka and her police colleagues undertake two parallel investigations, but fairly early on they guess the answer to one, and for the other there are no solid red herrings and only a couple of concealed clues. But many police procedurals aren’t built around solving whodunits; the challenge for the cops is amassing evidence before the criminal strikes again, and that’s how this story works, too.

I know this observation might perpetuate gender stereotypes, but female readers, especially those who know Pierce’s other books, seem most excited about figuring out the relationships among the characters: What fella is Beka going to end up with? How is she related to descendants in other volumes? The other male Fantasy/Science Fiction Cybils judge and I focused on the magical milieu, and were left unexcited: it’s a standard sword-and-sorcery world. (But to break that gender stereotype, Pierce herself is reportedly most interested in the magic and weaponry, a little baffled by her fans’ excitement about who likes whom.)

In the book’s prologue we meet Beka as a girl of eight years, bold enough to grab the Lord Provost’s attention by grabbing his horse’s bridle. Impressed, he takes her and her family into his noble household. Yet when we next meet Beka, six years later, she’s cripplingly shy, peering out at the world through her bangs and able to croak out only a few words in front of an audience. The better for reader identification, perhaps?

In fact, Beka has so much going for her, it’s almost complete wish-fulfillment for a teenaged police officer (or teenaged reader). Her cat talks to her. Pigeons talk to her (well, the troubled souls of dead people who ride on the pigeons’ backs do). Dust devils talk to her. As someone said last year about Chasing Vermeer, this is a book in which clues find the kid rather than the kid finding the clues.

The book started slow for me, but eventually I found myself intrigued by Beka’s story and rooting for her success. What stopped me from fully enjoying Beka Cooper: Terrier is how Pierce wrote it in diary form. In fact, I thought it was one of the least convincing, least compelling fictional diaries I’d read in a long time. Shortly after finishing the book, I heard Pierce’s Random House editor speak at the SCBWI conference in New York. She reported that this was the first novel Pierce wrote in the first person, so I suspect she chose the diary form to feel more comfortable in that mode.

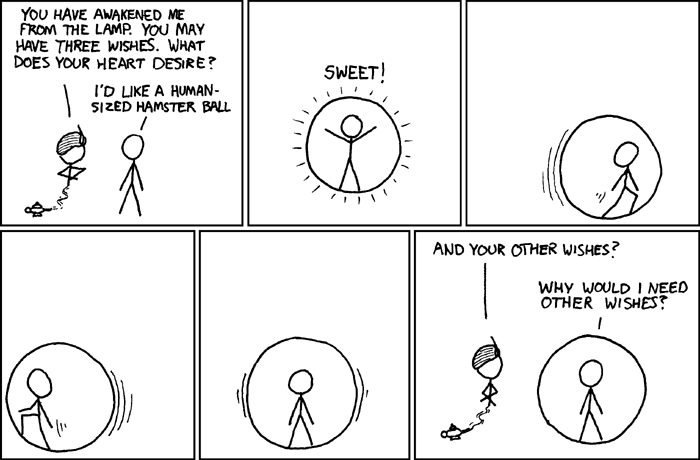

Personally, when I read (or write) a book in diary form, I want the document itself to play a role in the story. In this case, for instance, Beka could have looked back in her journal and seen clues that she’d forgotten. A diary might also be commented on, stolen, lost, abandoned and resumed, and so on. I guess this is a variation on the Heisenberg Principle: once a character starts recording her life in a diary, that life shouldn’t be the same anymore.

Why? Because we need an extra dimension of interest for all the limitations that come with a diary. In a realistic diary, especially one written for the diarist alone, the perspective of each entry is how the character feels when he or she write, not earlier in the day. Thus, if I’m writing a diary entry after breaking my leg, I’m going to start with my broken leg and how that’s making me feel right now. I’m not going to start by painting a picture of how my day began hours before. My leg hurts, dammit! So that makes a realistic diary a difficult narrative tool; it offers immediacy, but immediacy to the moment of writing, not the moment of action.

Beka Cooper: Terrier is full of moments narrated in great detail, external and internal, which means that its diary entries are completely unrealistic. On page 80, Beka arrives home physically exhausted--and proceeds to write more than 52 pages! And that's on top of 12 pages written at some point that morning--exactly when she finds the time is unclear.

There are a few writerly tricks to remind us we’re supposed to be reading a document, like a smear of ink on one page. But those tricks don’t really work. One night Beka comes home a little tipsy (page 350), so her diary includes typos: “teh Fog Lanterun.” We make errors like that when we type drunk, not when we write with a quill pen drunk. The prologue includes a diary entry from a semi-literate relative. But semi-literate people don’t keep detailed diaries. Most important, those types of narrative intrusions (what I called a “Paper Trail” in a presentation last spring) distract from the story rather than adding to it.

Three hundred years ago, as the novel was just being established in English literature, readers may have expected the frame of a memoir, biography, series of letters, or diary to explain why someone is telling us all this. But we don’t need those crutches anymore. We’re happy to follow a character describing his or her story in detail for no explicit reason at all--as long as that story is exciting. And Pierce’s story is exciting enough. It would have been more graceful without the unnecessary diary format, and I hope Pierce has the confidence to ditch that element for her next Beka Cooper volume. Her first-person voice works just fine.

Earlier this week I wrote about the rebirth of the British Empire in Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus series and Philip Reeve’s Larklight (which will officially become a series in October). I harped on how both authors seem to shy away from awkward elements of the real UK’s imperial history: oppression of peoples in south Asia and Africa, border-drawing in the Mideast, trade wars in China, etc.

Earlier this week I wrote about the rebirth of the British Empire in Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus series and Philip Reeve’s Larklight (which will officially become a series in October). I harped on how both authors seem to shy away from awkward elements of the real UK’s imperial history: oppression of peoples in south Asia and Africa, border-drawing in the Mideast, trade wars in China, etc.